This story, “Wild Horses Were His Game,” first ran in the September 1949 issue.

DICK CHURCH was a killer with no rival in all the wild Chilcotin. No other had so many notches on his gun. But his victims were wild horses and his killing was done in the employ of the Province of British Columbia. His fee was $75 a month plus one dollar for each set of ears—and the necessary ammunition.

Up to 1924 great bands of wild horses roamed the rugged mountains and lush valleys of the Chilcotin, a somewhat indefinite area located in west-central British Columbia and drained by the Chilcotin River and its tributaries, which have their origin in the wild and forbidding fastnesses of the Coast Range and pour their waters into the lordly Fraser some forty miles below the town of Williams Lake. While an occasional band strayed beyond these boundaries, almost the entire wild-horse population of the province was confined to this particular area.

Read Next: Beasts of Burden: Wild Horses and Burros Are Dying Hard Deaths in the West

This peculiar circumstance and the origin of these horses remain a mystery to this day. The rugged, snow-covered crest of the Coast Range might constitute a barrier on the west, and the swift Fraser in its deep gorge could well stop them on the east. But neither on the north nor on the south was there anything to hinder their movement. Yet the horses stuck to their chosen land.

How did they get there? Old-timers say they were there when the white settlers first crossed the Fraser and drove their herds into the lush pastures of the Chilcotin Valley. Those familiar with the history of the country offer two possible solutions to the mystery. The first—and most widely held—is that strays from the early Hudson’s Bay Company’s posts in the area reverted to the wild state. The second holds that Nemiah, the famous outlaw of the late decades of the nineteenth century, kept a large band of horses at his hide-out in remote Nemiah Valley, northwest of Whitewater Lake. After his capture in the early 1890s, his horses went wild. Both theories have serious flaws. But, whatever may be the correct explanation of the presence of the wild horses, they were undeniably there, in great number.

The Chilcotin is a cattle country, containing some of the finest range in western Canada. For years the cattlemen had complained of the depletion of the range by the bands of wild horses. They also claimed that the roving bands enticed many of the ranch horses, which in turn went wild.

The pressure became so great that in 1924 the province ordered a campaign of extermination, which lasted for two years and resulted in the killing of something over 1,200 head by official count—to say nothing of the far larger number accounted for by the residents and especially the cattlemen. The killing was in full swing long before the government took action and has continued right down to the present. There are still a few bands of wild horses in the Chilcotin, but these are being ruthlessly exterminated by the cattlemen. Some estimates place the total kill at 8,000 to 10,000 head.

Wild horses running like the wind, manes and tails flying, the thunder of hoofs on the valley floor, the wild neighing of stragglers, the shrill whinnies of the colts bringing up the rear—it is hard to imagine a more dramatic scene.

During the two-year provincial campaign Dick Church accounted for a total of 613 horses, or about half of the total official kill. His hunting was confined to the winter months when farm work was slack. On his best day he collected thirteen sets of ears, and in his best month—March, 1925—152 sets.

One of the most remarkable features of Dick’s hunts was his amazing display of courage and endurance. With a four- by six-foot tarpaulin for shelter, his gun, and the meager supply of food he could pack on his one saddle horse, he plunged alone into the wildest and most rugged sections of the Chilcotin and would not show up for months at a time. He lived mainly on game shot from the trail. When night came on, he sought shelter under a pine, cooked his meal in the two vessels in his outfit (a skillet and a coffee pot), wrapped himself in his blankets, rolled up in his tarp, and lay down in the snow. This in weather often 20 below zero!

Most of the killing was done with the rifle, but sometimes he employed other weapons. On a dark winter day when the snow was deep he found a band snowbound and killed eight with a club. At another time he roped three, dispatching them with a club. Skillful use of his hunting knife accounted for several other members of the band.

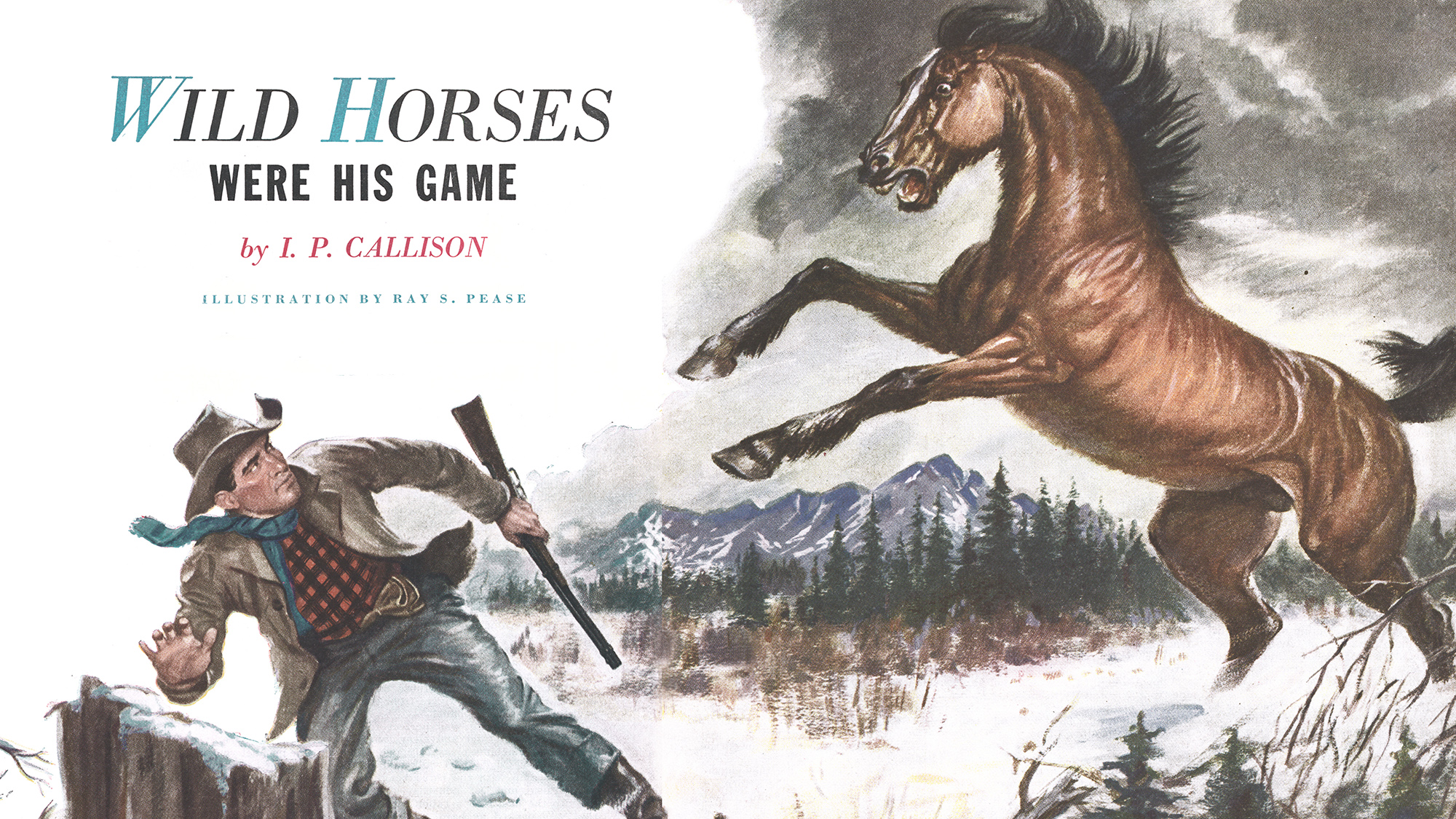

Dick had some narrow escapes. One time a wounded stallion hid behind thick brush at the edge of a meadow. When Dick approached, the stallion charged. A handy stump saved the hunter’s life. Dodging behind this, he shot the animal as it charged past. On another occasion a stallion charged without apparent provocation. Teeth bared and ears back, he was an ugly adversary. It took four shots to bring him down—and he fell at Dick’s feet.

Thrown by a “Dead” Horse

Once Dick shot a stallion and the animal dropped in its tracks, apparently for keeps. Dick got astride the fallen horse to retrieve the ears as evidence for collecting the bounty, when the stallion suddenly came to life, jumped to his feet, and threw Dick for a goal. Landing head first, he was almost buried in the snow. However, he recovered in time to land a well-aimed bullet just as the horse was disappearing in the timber

Another time, Dick and his brother drove a fine young stallion into a pocket in a high basin, intending to rope and tame him. It looked like a cinch. There was no avenue of escape except over an almost perpendicular shale slide. To their utter amazement and chagrin the horse plunged over and galloped down the steep slope, escaping unharmed.

According to Dick, wild horses are the wildest things in the woods. When scared they seem to go crazy and tear away at top speed. Running as if they were blind, they crash headlong into any obstacle that may be in the way. Often he saw them run squarely into trees. Hitting with a resounding crack, they would bounce back like a rubber ball, then quickly pick themselves up and start all over again. They are really tough. The only evidence of damage from these collisions is an оссаsional blind eye or a clipped ear. Because of their wild nature the horses seek the high basins during the summer, much the same as sheep and goats, leaving these remote areas only when driven out by snow and hunger.

It is a thrilling sight, Dick declares, to stand on the rim of a high basin and watch a band stampede when the hunter’s presence is discovered. Wild horses running like the wind, manes and tails flying, the thunder of hoofs on the valley floor, the wild neighing of stragglers, the shrill whinnies of the colts bringing up the rear—it is hard to imagine a more dramatic scene. The climax comes when a big stallion, his sleek coat glistening in the sun, his great mane flying in the wind, head high and ears forward, leads his flock across the wide valley and into the timber with incredible speed.

Dick says that, as a rule, the wild horse of the Chilcotin is much smaller than the tame horse. Most of them can be classified as scrubs, but occasionally a magnificent specimen is encountered. Dick believes that the horses were normal in size at first, but that the severe winters, improper food, and inbreeding have produced these stunted animals.

They are easily tamed after they lose their fear of man. Dick and his brother roped and broke wild horses during the winters when there was not enough farm work to keep them busy. In the winter of 1914 the brothers caught and broke seven for use around the farm and on the range. Because the animals are tough and can shift for themselves they make excellent saddle horses for use on the range or for traveling in rough country.

The few bands of wild horses remaining in the Chilcotin stick to the wildest and most inaccessible basins. To the best of Dick’s knowledge, two small bands on the Porcupine west of Big Creek and one on Saddle Horse Mountain west of the Chilcotin River are the only survivors. There may still be some in Nemiah Valley west of Whitewater. These bands are smaller than those that roamed the country before the provincial campaign of extermination. They now number six to eight to each band as against twelve to fifteen formerly. On one occasion Dick saw between eighty and ninety head in a small meadow on Porcupine Creek, where they had been driven down by the snow.

It appears now that the wild horses’ finish is near. The cattlemen still pursue them relentlessly and shoot on sight. The bands, however, are still being recruited by strays from the ranches. These go wild quickly and are as difficult to find and as hard to catch as those born wild.

Toughness of the Pioneer

I’ll end this story with an incident that illustrates the toughness of the pioneer. On his way home from one of his horse-hunting expeditions, Dick undertook to ride across Big Creek on the ice. When he was about the middle, the ice broke and rider and horse went to the bottom. Dropping his gun, Dick fought desperately to get out. The current was pulling him under the unbroken ice, and the bitter-cold water was rapidly paralyzing his ability to fight. Putting forth every ounce of energy, he reached shore after a frantic struggle. Grasping an overhanging bush, he was able to pull himself up the steep bank. When he reached shore and looked back, only his horse’s head was above water. The narrow creek and steep bank made it impossible for the animal to fight his way out.

It was Dick’s favorite saddle horse. To stay for any considerable time in the icy water meant death for the animal, but Dick could do nothing alone. It was in the dead of night, and the nearest ranch was two miles away. Without a moment’s hesitation Dick started off on the double-quick. Finding that his riding boots filled with snow and slowed him up, he quickly discarded them and ran the remainder of the distance in his bare feet. By the time he reached the ranch, his feet were bruised, cut, bleeding, and almost frozen. But his heroic sacrifice saved his horse. Rushing back with help and a team, he pulled the animal out of the stream.

This text has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards.

Read more OL+ stories:

• Beasts of Burden: Wild Horses and Burros Are Dying Hard Deaths in the West

• Lost in the Gloom: A Dream Mountain Goat Hunt Turns into a Nightmare