My living nightmare started in February of 2019. That’s when my 2-year struggle with Lyme disease began. I never even saw the tiny, poppy-seed-sized tick that got me. And I never saw a bullseye rash. It was six months before I got a diagnosis. By then, the microscopic spirochetes that cause the illness had worked their way into my joints. A simple two-week course of antibiotics would not fix my problem. I didn’t know it then, but I had entered a struggle where constant joint pain, crushing insomnia, and a never-ending flu-like brain fog would haunt my every step.

The Outdoor Life Podcast: The Mysterious Chronic Lyme Disease Nightmare

Today, I’m older and a little wiser. After countless prescriptions and doctors’ appointments, and interviewing several of the top Lyme researchers in the field, I know a lot more about Lyme disease and ticks than I ever wanted to. I’m also largely symptom free.

But it didn’t come easy. The good news for you is, I can pass those years of knowledge on to you in a few minutes, so you can arm yourself against this damaging disease.

The Trouble With Detecting Lyme Disease

The real problem with Lyme isn’t that it’s hard to cure. It’s not — if you know you have it in the first month. In that case, a quick course of the right antibiotics is enough to cure you permanently. Or at least until you get another tick bite. The problem is what happens if you don’t catch it in time.

“We typically see manifestations of chronic symptoms occurring when there’s any sort of delay in diagnosis or treatment,” says Dr. Shannon Delaney, Lyme researcher at Colombia University.

Those chronic symptoms show up in what’s called post treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). They happen in about 20% to 30% of Lyme sufferers, making Lyme the painful elephant in the outdoor-lover’s living room. Many victims turn to Lyme specialists or “Lyme literate doctors.” Others suffer in silence. Still others may not even know they have it. There’s also no test that proves you’re cured. So, if you get the “cure” but you’re still sick, what then? The answer is a deep, wide trail of suffering for millions.

A Hidden Epidemic

Each year, approximately 35,000 new cases of Lyme disease get reported. Yet the CDC estimates that there are 476,000 people diagnosed and treated each year. That’s nearly 5 million infected Americans in the past decade alone.

The massive difference in those numbers comes from a hiccup in the reporting process. The CDC only counts a new case of Lyme if the doctor who treats it fills out a special CDC report. Doctors are busy, and they often don’t take that extra step. But there may be even more cases than we know, since many Lyme sufferers may not get diagnosed at all.

According to a nonprofit called the Global Lyme Alliance, the initial test most doctors use for Lyme, called the ELISA test, has a 50% false negative rate.

Dr. Delaney agrees that current testing methods leave a lot to be desired. “It’s pretty universally acknowledged that the primary tests for Lyme disease are insensitive,” she says. After all, the tests don’t look for the organism in the victim’s body. They look for the body’s immune response, which can be a moving target.

Dr. Eva Sapi of New Haven University’s Lyme Research Center, goes further. “There may be as many as 200 strains of Lyme disease out there,” she says. “Yet the tests we have today only work for a small number of those species.”

But this all gets even more complicated when Lyme researchers and medical officers don’t necessarily agree.

“It’s possible that there are species of Borrelia we haven’t identified,” says, Dr. Christina Nelson, Medical Officer at the CDC, noting that a couple of new species have been discovered in the past few years. “But you’d expect these to show up on standard Lyme antibody tests, since different species of Borrelia often cross-react on those tests.” She also argues that the tests are not insensitive during later stages of infection. “The vast majority of people who have disseminated Lyme disease develop an antibody response that shows up on the standard tests.”

One problem with the testing everyone agrees on is the timing. Dr. Marcelos Campos, Chief of Internal Medicine at Atrius Health in Boston, who also teaches at Tufts and Harvard Universities, says it matters when the test is given.

“So for example, if someone gets bitten by a tick, and they get tested five or seven days later, it will most likely be negative because the test is looking for a response that hasn’t started yet,” says Campos. One testing lab called IgeneX attempts to solve the testing problem with a more lenient standard. So far, the CDC doesn’t recognize IgeneX’s testing panel, though many doctors currently rely on it.

There’s No Lyme Disease Vaccine

There was a simple, safe, effective vaccine for Lyme disease about 20 years ago. Dr. Sam Telford, Director of the New England Regional Biosafety Laboratory at Tufts University, helped develop it in the early 1990s. “Sadly,” he says, “it now sits on a shelf.”

Telford and his team came up with a unique method where the vaccinated animal’s blood came into the tick and killed the bacteria before they had a chance to get into the body. SmithKline Beecham company, now GlaxoSmithKline, optioned the vaccine and tested it in three-phase clinical trials with 8,000 subjects, finding it safe and 60%–70% effective in preventing illness. The FDA approved it for sale in 1998, but the company withdrew it in 2002 because of lawsuits.

“Lyme disease activists said, Oh, well this vaccine gave us Lyme disease, or it gave us arthritis,” Telford said. “They instituted a class action lawsuit against SmithKline to the tune of $1 billion.”

The CDC said there was no medical basis for the lawsuit, and it was thrown out of court. Still, the company got cold feet. “They withdrew the vaccine from the market, and it’s been sitting in their freezer ever since.”

In the meantime, a veterinary vaccine maker known as Meriel packaged the vaccine for use in dogs. “It’s essentially the same one that went through human clinical trials,” says Telford. “So we can vaccinate dogs against Lyme with a vaccine that is safe and effective, but we can’t do it for humans.”

There’s hope on the horizon though, as Pfizer has pushed a new Lyme vaccine into phase II clinical trials. Even so, it could be five years or more before that new vaccine is on the market.

We Don’t Fully Understand Lyme Disease Yet

The traditional Lyme treatment of two to three weeks of doxycycline may not be adequate.

“We have multiple confirming studies that suggest that doxycycline doesn’t eliminate the infection,” Dr. Sapi says.

Lyme-literate doctors and researchers claim the spirochete that causes Lyme disease is incredibly resilient. They say antibiotics may not kill it in some cases, but may merely knock the tail off it, forcing it to wait in a dormant, cyst-like form until the antibiotics are removed. They also claim that it secretes slippery liquids called “biofilms” that antibiotics can’t penetrate, then hides in them until the danger is past. The CDC doesn’t acknowledge these claims.

In one study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, DNA from Lyme spirochetes was found in the spinal fluid of 96% of chronic Lyme sufferers, even after a month or more of antibiotic treatment. The CDC’s Dr. Nelson points out that DNA doesn’t prove the presence of live organisms. But other studies show that after treatment, live Lyme spirochetes were found in the tissues of both mice and monkeys.

Dr. Nelson argues that animal studies can be problematic also, since researchers sometimes inject the animal with more spirochetes than they’d get from a tick bite in the wild. Also, there’s no evidence that extra rounds of antibiotics speed recovery. In fact, long-term Lyme may be caused by the body’s own autoimmune response.

“I often wonder lately if the mechanism of what’s called chronic Lyme may have some similarities with the long-haulers from COVID we’ve been treating,” says Dr. Campos. “People get sick, and we treat them and they recover. But some continue to have symptoms from an increasing inflammatory response. That makes me wonder if we are dealing with the same mechanism behind both problems.”

In other words, chronic Lyme disease may be something like a giant allergic reaction — sort of like a case of poison ivy that runs rampant through the body’s systems, even long after the irritant is gone.

The Wrong Treatment Can Be Dangerous

The CDC cautions against seeking treatment for Lyme without objective signs of an infection. “Some patients who’ve been told they have chronic Lyme disease don’t have that evidence,” says Dr. Nelson. “They may have depression, multiple sclerosis, cancer, or an autoimmune disease. And yet the patient still gets told that they have chronic Lyme. That can be extremely dangerous, because the patient misses out on potentially lifesaving treatment time.”

Getting the wrong treatment — like antibiotics when you don’t need them — can also cause life-threatening conditions such as c. diff. That’s a bacteria that can grow out of control in an intestine sterilized with antibiotics. (In my case, this wasn’t a problem. I took different antibiotics for seven months, but my specialist used protective probiotics to repopulate my gut with healthy bugs.)

Dr. Nelson cautions also that “Lyme literate” is not a certification, but a self-anointed term. Another problem with Lyme-literate treatments is that they may not be covered by insurance. My treatments ran into the thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket costs. Today, I wonder if I could have saved myself a lot of money with a few key lifestyle changes (more on that later). Still, for the patient who is suffering and not satisfied with their general practitioner’s approach, a Lyme-literate doctor may be an attractive option.

Where Does Lyme Disease Exist?

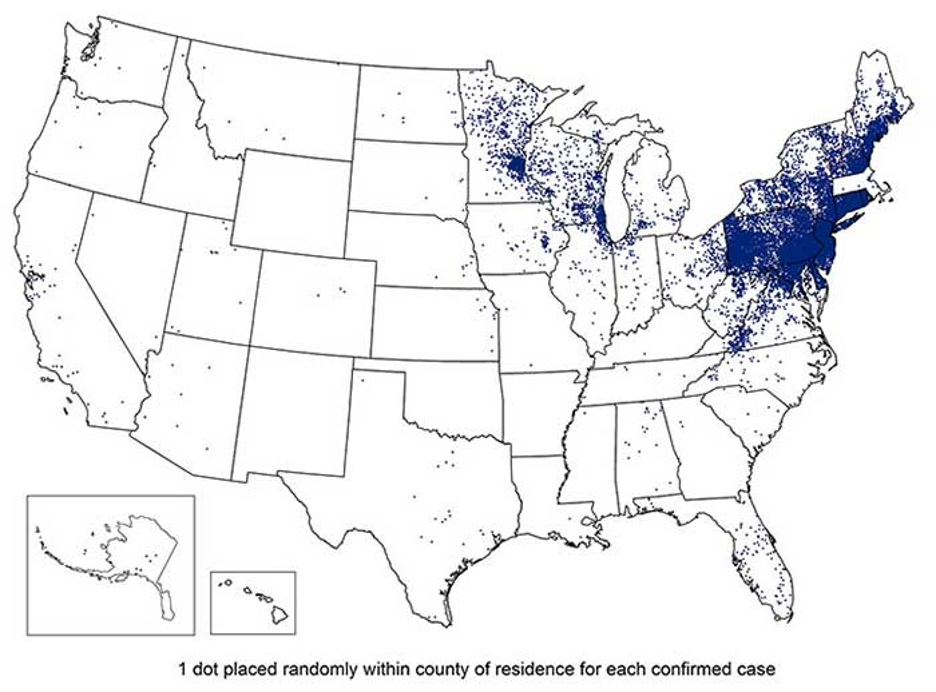

As Lyme spreads throughout the country, the knowledge of how best to treat it may lag behind the disease. As of 2021, Lyme cases are clustered mainly throughout the northern states east of the Mississippi River, with the heaviest concentrations in New England and Pennsylvania.

But the disease is spreading, and doctors outside the dense blue areas in the map above may be slow to catch up on the science. They may not know to test for Lyme when faced with the symptoms, and they may not know to test more than once. There’s also a lower chance they’ll know how to treat the disease.

That was certainly the case with my Lyme diagnosis. I felt lucky that the test caught my illness, but I wasn’t satisfied with the prescription of two weeks of doxycycline. Nor did it solve my problem.

“Doctors who practice in endemic areas generally know more about the illness,” says Dr. Nelson. “They often read more about it, see more cases of it, and get more training on it.”

Delaney goes further. “Even in the Northeast, many doctors have a difficult time diagnosing Lyme disease or even understanding it,” she says. “I hear from patients all the time who — like you — had to research their own symptoms. And they were suspicious about Lyme disease and went to their doctor and said, hey, can you test me?”

Camouflaged Lyme Disease Symptoms

One reason Lyme is such a moving target is that its symptoms can make it look like other diseases. In fact, it’s been called “the great imitator,” because it often masquerades as MS, depression, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and several others.

If you don’t spot the telltale bullseye rash, or see a tick fastened onto your skin, you may not know you have it until you become very sick. Since about a third of Lyme cases don’t come with an obvious flag like that, the illness often slips through the healthcare net. That’s bad.

“If left untreated, Lyme spirochetes can cause all kinds of problems,” says Dr. David Crandell, Director of the Dean Center for Tick Borne Illness. “They can permanently affect your joints, your tissues, and eventually your major organs, like your heart and nervous system.”

According to Dr. Sapi, Lyme can even cause endocarditis — a life-threatening inflammation in the heart that can be deadly. Since my own struggle with Lyme played out, I’ve often wondered if it caused my brother Paul’s sudden cardiac death over 20 years ago. He was an avid hunter, fisherman, and all-around outdoorsman, and could very well have died from an undiagnosed case of Lyme disease that infected his heart.

The Key Symptom: Traveling Joint Pain

One dead giveaway for Lyme that all doctors agree on is traveling joint pain. That’s pain that starts in one joint and vanishes, showing up in another and another, and sometimes going away for weeks between bouts. There are very few other diseases that have that symptom. If you have traveling joint pain, you should seriously think about getting a Lyme test.

In fact, that moving joint pain was what tipped me off to get my son in to see a specialist when he suddenly got sick. I knew from experience that it wasn’t normal that he woke up crying, complaining of pain in one knee one night, another knee another night, and his elbow on a third. (He also slept all day, which was highly unusual for him, and one side of his face swelled up so bad one day that he looked like a different child.)

But it was incredibly frustrating to get treatment for him. His pediatrician agreed to test him, but the results came back negative. When I pressured her, feeling like a nut, she agreed to escalate the problem to the state’s chief epidemiologist. He tested my son, again with negative results. But the symptoms persisted. That’s when I asked my Lyme specialist about it.

“Eighty percent chance he’s got Lyme, just based on the traveling joint pain,” he said. “Twenty percent chance he doesn’t. And no, we don’t want to prescribe antibiotics if he’s not sick, because that can cause problems. But if this was my kid, I would definitely have him on an antibiotic.”

After a telehealth visit with my son, he prescribed the medication, along with a stomach-protecting probiotic, and the symptoms left and have not returned, even years later. According to Dr. Delaney, who specializes in treating children with Lyme, my family is not alone.

“I wish I could say that your encounter, with your own personal history of Lyme disease and your son’s probable history of Lyme disease, is a rare one,” Delaney says, “But this is a classic story I hear from most of the patients that I see.”

Delaney’s patients often tell of doctors who are resistant to testing or treating for Lyme. “Often, the patient can’t get the early diagnosis or treatment they need. Then they start getting sicker and sicker.”

These patients end up seeing multiple specialists, and sometimes months or years after the initial symptoms, they finally arrive at a diagnosis.

Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Illnesses

Another reason Lyme is such a tricky issue is that it’s not the only tick borne illness. To date, we know of 16 diseases carried by ticks. Some are known as common Lyme “coinfections,” because they’re often carried by the blacklegged “deer” tick — the one that carries Lyme disease. And as my Lyme specialist pointed out, not all doctors know to test for coinfections like anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and a variant of Lyme called borrelia mayoni.

My coinfection test panel showed I was positive for bartonella — commonly known as cat scratch fever. Other researchers I’ve interviewed have since told me that there’s no evidence of that particular disease in blacklegged ticks. But the others are certainly worth worrying about, and not all of them are cured by the same course of antibiotics prescribed for Lyme disease.

It’s worth noting that our country’s growing Lyme epidemic is rooted firmly in our growing anti-hunting stance. That’s based on testimony from Dr. Telford, and from Dr. David Stainbrook, chief biologist at the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife. Since 1995, hunting bans have skyrocketed, leading to a 400% increase in the deer population in Eastern Massachusetts. During the same time and in the same area, Lyme disease has increased 6,600%.

Hope for Chronic Lyme Disease Treatment

There’s a bright light at the end of the chronic Lyme tunnel. There’s some anecdotal evidence that a ketogenic diet may fight chronic Lyme disease. The science on it is still thin, but eating less sugar (both simple and complex) can help reduce symptoms.

In a similar way, intermittent fasting (IF) may help. For me, it seemed to be the cure. As my symptoms continued to ramp up for 18 months, I became increasingly frustrated. I tried intermittent fasting on a whim, simply skipping breakfast and eating a big, late lunch and dinner.

In four days, all my Lyme symptoms had vanished. A month later at my regular checkup, they hadn’t come back. My specialist was so encouraged that he took me off all my medications. “Unless your symptoms return, I think we’re done,” he said.

That was 18 months ago. My symptoms have not recurred, except briefly, any time I eat too much sugar.

The idea that keto and IF may help fight Lyme is not surprising. Lyme is inflammation-based, and there’s a large body of evidence that both IF and keto fight joint pain and inflammation.

Even so, good nutrition is an important element of fighting any illness.

“You’d expect that with better nutrition, Lyme symptoms would decrease,” says Dr. Crandell. With his patients, he focuses on improving sleep, exercise, and nutrition, thereby allowing the body to conquer the disease.

How to Prevent Lyme Disease

So far, the best protection against Lyme disease is knowledge, mixed with vigilance. Use tick repellent when you go outdoors. DEET works best, but if you’re not a fan of harsh chemicals on your skin, there are alternatives. I treat my woods clothes with permethrin — a long-lasting repellent that sprays onto fabric in one coat and lasts six weeks, keeping the chemical (and the ticks) off your skin. (If you go this route, wear a respirator and eye protection while you spray.) You can also use a natural, plant-oil based repellent with ingredients like lemongrass and peppermint. Those work, but only for about an hour, so you need to re-apply them frequently.

You can buy tick-treated clothing for dogs, too. That’s a good idea, because dogs are one of the biggest entry points for bringing ticks into our homes.

“The dog is out in the woods or out in the yard, and it comes home with a tick on it and then it’s on the couch or on your bed,” says Dr. Crandell. “So for many people, protecting the dog is as important as protecting yourself.”

Beyond prevention, watch for the symptoms. Obviously if you see a tick or a bullseye rash on your skin, get tested. But don’t stop there. Even if you don’t see a rash or tick, get tested if you notice joint pain that moves from place to place. And finally, don’t rely on a single test. Get tested early, then if the results are negative, get tested two or three more times, waiting a few weeks between each one. Repeated tests will give your antibodies time to multiply enough to register.

Finally, there’s hope around the corner. Along with a new Lyme vaccine on the horizon, researchers at UMass are working on a “monoclonal antibody.” To cut out all the medical terminology, it’s a shot that creates a boost of antibodies that last a couple months. Then if you’re bitten by a tick, your blood acts as protection.

Either way, Lyme disease is here to stay. As deer and tick populations continue to expand, we can expect to see more ticks in more places, and more cases of the illness.