“This isn’t going to be good,” I thought to myself, as the wind I had been fighting against for hours suddenly fell still. After maybe 2 or 3 seconds of silence, I was smashed by a gust that instantly flattened my tent “Well, I guess I’m leaving now,” I muttered as I crawled under the rain fly and began quickly stuffing gear into my backpack with a necessary, but forced sense of calm, despite feeling panic and frustration. I had no choice, my hunt was over.

The first day or two of any sheep hunt is almost always a shock to the body, and as I laid down in my tent that first night, some light muscle spasms in both legs served as a foreboding reminder of the difficulties that were ahead. I had decided to hunt sheep alone with a recurve bow, and with over a decade of sheep hunting experience I knew the odds were almost insurmountably against me. Still, I felt confident that night. I had passed by a group of rams early in the afternoon, determining one to be legal by full-curl, and another to be likely legal by age.

They were tucked away in what I considered a safe place, an out-of-the-way bowl that no one was going to stumble into, despite it being a fairly high-pressure area. Up until the point of carrying a recurve with me into the mountains, just finding a legal ram to hunt was usually one of the biggest challenges. Given time, weather, and patience, any ram is killable. Having a day and a half until the season opened, and not wanting to risk driving the sheep from their hidey hole, I moved on to check other areas.

I don’t think there is much debating that bowhunting Dall sheep is truly one of the most challenging hunts you can undertake. Of course, the physical aspects of backpacking and hunting in the mountains these rams call home are daunting, as is the constant struggle to stay positive and motivated in the search for a ram. The combination of their habits, haunts, and incredible eyesight make them tough to get close to, but add in a recurve or long bow, and the level of difficulty gets heightened. Anyone who succeeds in this venture deserves respect, and I hoped to be among those by the end of this trip.

Closing to Within 100 Yards Twice

By opening day, I had yet to find any other rams, so I hoped that I hadn’t made a critical mistake by letting the ones I found out of my sight. I packed up camp and began working my way back up to the top of the ridgeline to the basin where I spotted the rams days earlier. At about 10:30 a.m., I got my first view into the basin and saw four sheep, sure to be those rams. A second later, I saw what I was dreading most, another hunter. A quick look through the binos, and I saw him glassing atop a ridgeline. He was unknowingly within half a mile of the rams I had returned to hunt, and there was nothing I could do, but casually make myself visible to him (but not the sheep) atop my own ridge. To my relief, he continued on his way, in the opposite direction.

A group of Dall rams will typically bed down for several hours in the afternoon to digest their morning’s grazing, which gave me plenty of time to make a camp in the only suitable spot I could find, slightly off the back side of a saddle on the ridgeline, where my tent would be obscured from the sheep’s view. Once in a better position, I planned to get as close to the rams as I could without spooking them and wait for my chance to close the distance. I had been shooting deadly with my recurve out to 55 yards, but knew it was going to be difficult in the wide-open terrain. After a few hours, the rams began filing down the mountain towards the green grass near a spring. They fed and watered in a small washout in the middle of the basin, about 300 yards below me.

Gradually, the rams worked directly below me and were obscured by the terrain. I began sliding down the hill towards them, careful to be as flat to the terrain as I could. Suddenly I saw the back of the rams and they were quickly moving up the hill towards me. I nocked an arrow and laid flat against the ground. One ram spotted me at about a hundred yards, but his uncertainty didn’t startle the group. They continued working to my left, and as soon as I could, I crawled back to the ridge top and hurried to get in front of them. I repeated this scoot down the hillside until I saw them bedded. I ran out of cover to hide behind at about a hundred yards as they bedded down again. Our stalemate lasted the evening, and when the rams got to their feet, they were headed back in the opposite direction, grazing at that same washout again. After closing to 100 yards twice that day without blowing those rams out of the country, I was starting to feel better about my chances.

Act Like a Sheep to Kill a Sheep

The next day, the rams followed a similar routine, back and forth across the basin, with just enough randomness in their pattern to protect them from me. As a rifle hunter at heart, I wasn’t used to spending days within rifle range of legal rams, and my hunt would have been over within a couple hours on the first day. One thing that was becoming apparent though, was that the spring they kept coming to feed at was key. It was most likely some sort of mineral lick. I stayed with the rams all day, but could never get closer than 250 yards or so while remaining out of sight, and bet your ass, a Dall ram will see you instantly inside that distance if you expose yourself.

I awoke the following morning with even more confidence that I would be able to find a weakness and get a shot at this ram. Except they were gone. The basin that the rams had hidden out in for days was void, bringing about a feeling of hopelessness. Even with the high ground, and rams in sight, the odds are still low for someone carrying a recurve. With the rams gone, the game started all over again. I decided to sit in a spot that I could watch the basin, next to a saddle that caribou had been trickling through. If a big enough bull walked in, I would try to shoot him. A few small bulls had come by, and at about lunchtime, I set my bow down with a nocked arrow, and nestled in a small pile of rocks. I unwrapped a granola bar. Halfway through it, a giant bull caribou walked in to 20 yards. I dropped the bar and grabbed my bow, hoping he would freeze. Instead, he reared up like a horse and quickly disappeared over the ridge.

As luck would have it, not long after blowing my opportunity on that caribou, I spotted a lone ram coming toward me from across the basin. I looked down and saw the other three rams. I’m not sure where they had come from or how I missed them. The rams congregated tightly, feeding in their favorite spot, and I put on my sheep costume, a white hooded sweatshirt. After a few minutes, the rams fed up against a small, steep, but grassy shelf, putting them completely out of sight. As quickly as I could, I ditched my pack, grabbed my bow, and ran down the mossy hillside straight at the rams. I slid down behind the last bit of cover, a small hump just to the left of a stream bed washout that cut down through the shelf. I peeked up to see the rams backs moving towards me at 65 yards. If they continued their path, I would be presented with about a 30-yard shot.

As the anticipation built, the ram I was after veered to the left, and I was suddenly exposed at 80 yards. After an uncertain 15 or 20 seconds, the rams ran to my left. My heart sank, as I knew the likelihood of another opportunity was minimal. The rams stopped at about 250 yards, and I decided “what the hell, no one is watching, I’ll just act like a sheep.” I pretended to graze and act indifferent to the rams, slowly crawling back up the hill. It worked. The rams calmed down and even bedded, and I was able to get out of sight and back to the top of the ridge. After another couple hours, I was 120 yards above them, and the sheep had moved right back to where I had been. Running out of daylight, I watched them climb to a bedding area, sure that the next morning I was going to get a shot at that ram.

Read Next: New Hunting Gear is Great, But Confidence is the Real Key

Making it Off the Mountain

The wind woke me up at about 10:30 p.m. Wind and storms are just a part of life on sheep hunts, but this was a bad one. I’d weathered bad storms before, and initially was unconcerned, but the wind was getting worse. I had braced a couple of the weak spots of my tent with trekking poles, but that didn’t help much. After a couple hours, I decided that I needed to try and make a wind-break by stacking rocks in a wall on the upwind side of my tent, just to give the structure a bit of protection from the gusts. I’d seen Alaska Natives do this while muskox hunting.

The wind continued to blow harder, now with rain, and my makeshift wall wasn’t doing much good. I was having to sit up with my back against the wind to keep the tent from flexing. I kept thinking, “it can’t keep getting worse, it’s gotta break.” But I was wrong, and at 2 a.m., one of my guy lines snapped. I was already sitting in my rain gear, so I jumped outside to attempt a fix to stop the tent from being ripped off the top of the ridgeline and into the valley, a steep 1,500 feet below. That’s when it happened, the lull, the blast, and the sudden realization that my situation had become very serious.

As I packed my gear, I knew I would have to leave the tent. Trying to pack it in this wind would be futile and waste of time and energy I might very well need. Anything that was still dry, I carefully packed in dry bags, including my synthetic puffy insulating jacket and pants. I was sure to have an arduous hike ahead, so I stripped down to my underwear underneath my rain gear, put my phone in a dry sack in my chest pocket, and my GPS in a Ziploc bag in a cargo pocket. I said a little prayer and crawled out from under what was left of my tent, throwing rocks on top of it to secure it until I could come back.

Storms and sheep hunting go hand-in-hand, so I shouldn’t have been surprised, but this was like nothing I’d experienced in 16 years chasing rams. I had about a mile of ridgetop to navigate before I could drop elevation, hopefully escaping some of the wind. Much of the ridge was made up of basketball-sized rock, covered in black lichen that is common in sheep country. When dry, it’s as grippy and abrasive as sandpaper, but when wet, is very slick. With my headlamp narrowly lighting the ground in front of me, I had to time my short jaunts between violent gusts of wind that required me to keep my head down and brace myself. I remember repeating, “I can’t believe it’s actually this bad,” while being deafened from the flapping of my tightly-snugged raincoat hood. I had to be especially careful not to get off course, or twist an ankle in the rocks. If I got hurt, rescue would be impossible, potentially for days.

It was a painstakingly slow process, and the wind and rain were unrelenting. In the direction I hobbled, the wind was hitting my left side. It felt like being constantly blasted with a pressure washer. I’ve experienced 50 to 60 mph winds several times, and this was much worse. Wearing minimal clothes keeps you from sweating as much in rain gear, but you also get to feel every cold water drop blast you. I realized something was wrong after about 30 or 45 minutes. My left boot was saturated with water, then my right. It wouldn’t be abnormal for Gore-Tex boots to be overwhelmed and have some leakage, but I had them protected with gaiters and rain gear. I soon realized water was running down my body on the inside of my rain gear, and into the boots, filling them. Once it started, it didn’t take long for the entirety of my rain gear to become useless. The water blasted through the $1,200 rain suit like it wasn’t even there.

Eventually, I was able to drop enough elevation so that the wind became tolerable, and slogged my way back towards the truck, cussing every step of the way. I intentionally perpetuated the fury, as it kept me moving (a necessity at this point). I was now soaked with no shelter or useful barrier against the pounding rain, and hunkering down simply wasn’t an option. I had to keep moving. After about 8 hours, wet and dog-tired, I made it back to my truck, and started the long drive home to regroup.

Back Up the Mountain

In hindsight, it may have been a good thing that I was forced off the mountain early. That storm lasted longer than I would have had food for anyway, and I was able to get some rest and dry everything out. When the weather broke, I carried my bow back into the mountains. Ascending the ridgeline and peeking into that bowl, I almost couldn’t believe it when the rams were still there feeding. Another pair of rams had joined up, making six sheep total. In hindsight, I would have had time for an immediate stalk, but given that they were holding to their pattern, I didn’t want to rush in. I watched the rams from 200 to 300 yards all evening, content that I was going to kill the lead ram in the morning. I also noticed a second ram the group was definitely legal (by being over 8 years old).

I camped outside the basin, lower this time, and woke early in the morning. As I climbed the steep hill to relocate the rams, I happened to turn around and see six sheep bedded about half a mile in the opposite direction. One look with the spotting scope confirmed my fears, the rams had left their hideout, walked within a hundred yards of my tent in the night, and were on the move. I did my best to follow them, but could never get closer than about 300 yards for the next two days.

While all of this was going on, I had been in communication with my good friend and sheep hunting partner, Frank, who had a draw tag. He had just been snowed out of his solo hunt, had a close call with hypothermia, and was headed home. I informed him that the group of rams I had been following had at least two legal rams, and although it took him awhile, he came hiking into camp at about 10 p.m. one evening.

Although our spirits were lifted by having good company, the hunting didn’t get any easier. We woke to a healthy skiff of snow, and the icy August wind was a blunt reminder that winter was coming. It took us about half a day to locate the rams, and we tried to position ourselves as best we could as they moved into yet another drainage. From there, it turned into a waiting game. There was literally no cover or useful terrain to approach closer than 300 yards. The best we could do was to hover just out of sight, along a ridgetop trail. It would present a very close opportunity if the rams chose that route. It went on like this for several days, until we were almost out of food and vacation time.

This Archery Hunt is Over

On the eve of the last day, we finally had to have THE discussion. I didn’t want to go home without that ram, and Frank had been putting forth just as much effort as I had. We decided that on the last day, if we just couldn’t make an archery stalk work, Frank’s rifle would come out. This may be a mortal sin to a “purist bowhunter,” but I’ve never made claim to be such. I have hunted these white rams long enough to recognize a situation for what it is.

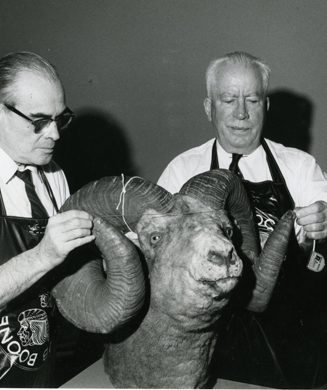

It didn’t take us long to find the rams, who had moved little more than a few hundred yards from the same spot we originally found them in. They were very exposed, but at the same time completely safe from my recurve. By mid-morning we decided to push the issue. We moved directly above the rams and began crawling down the hillside towards them. At about 300 yards, we were out of workable topography, so we resigned to using the rifle. First, we had to work out the issue of figuring out which sheep was Frank’s and which was mine. My full-curl ram was easily recognizable in the group, but the ram Frank was after, although old, looked very much like a ram in the group we figured was only 7 and not legal. We had one rifle, and two sheep to sort out. Picking and shooting one correct sheep in a group can be tough enough, but keeping track of another, switching the rifle, and shooting the correct one again is a challenge with potentially enormous consequences. While we were trying to collate this mess of rams, they simply stood up and walked away, down the mountain, over a mile towards the brush line, for no apparent reason.

We retreated back to the top of the ridge and were left scratching our heads. We worked back around the ridgeline as they began coming back to the other side of the bowl. Then, they did a 180 again and went almost 2 miles out into country you would never expect to find a Dall sheep in. As we walked, I said, “why don’t you just shoot your ram first, I can pick mine out easily afterwards.” This would solve a lot of the confusion as we should have time to sort them out before the shooting started, and if they bunched up, could easily pick mine out with binoculars in rifle range. We were almost back to camp, cussing under our breath at whatever instinct told these rams to get up and walk away. We knew they were bedded out of sight, obscured by a small hill, and we discussed the possibility of going after them, but it was too far and too late in the day. We sat glassing, hopes dashed, knowing it would take a miracle for something to work out as the sun descended towards the horizon on our last night.

Then, one of the rams started coming back. Then another, and another, until the whole group was skirting low on the ridgeline, back towards the head of the valley, where we sat perched. “They’re moving fast,” Frank said. “Once they go around the corner of that hill, we need to move.” The rams continued to come closer, and as we ran the ridge to cut them off, finally peering over the edge and seeing that they were no longer on the opposite side of the bowl, but now under us, we had them. “You’re not gonna need that thing,” Frank said, as I set my bow down before crawling to the edge of the bowl. The rams were 225 yards straight below us, and as Frank settled behind the rifle, I found and directed him to his ram. “The one next to the vein of rocks, on the top right, just lifted his head, on him?” “Yep,” Frank replied. I quickly located mine and held on him with binoculars. “OK, let him have it,” I said. “You nailed him,” I said, after hearing the thwack of the bullet. I saw his ram instantly fall in the periphery of my binoculars as my ram stood, startled. Frank rolled away from rifle, and I jumped on without taking eyes off my ram, and in a matter of seconds, he was on the ground too.

In the fading light, we gutted the pair of 10-year-old rams and propped them open, returning the next morning to begin the chore of caping, deboning meat, and loading backpacks. The agony of packing a whole sheep, camp, and the tent I had to abandon before was significant, but its severity was softened by the weightless feeling that a successful sheep hunt brings. I set out with the goal of killing one with my bow, almost had some good chances, and experienced a whole different sheep hunt than if I’d punched my tag by noon on opening day. I’m fortunate in that where I live, I can have a “hunt of a lifetime” nearly every year, and each one presents its own trials. I didn’t kill a ram with my recurve, but I certainly tried, and getting to have that experience and still come home with sheep meat left me satisfied, and that’s what’s important.