Let me tell you a secret: You can cook wild game with no motivation whatsoever other than dinner. You don’t have to post it to Instagram, or even take a picture of it.

In fact, if the only person impressed with your dish is your 5-year-old, that’s okay. Sometimes, it’s just a Wednesday night, and what that kid would like is one of Dad’s Sloppy Doe sandwiches: ground venison cooked in bacon grease with a can of Manwich and diced sweet pickles. He wants it on a bun with a slice of Velveeta and a bag of chips, and he wants it right now because there’s an hour of daylight left and a toad outside that needs catching before dark.

This is what wild-game eating actually looks like in a whole lot of hunting households across America. Does the Manwich or Hamburger Helper “mask” the taste of the venison? I guess it does. But if the boy’s gut is full and he’s happy, who cares? Eating game is a practice not because it’s hip, but because the freezer is full of it, and it tastes pretty good. We can tell people that and not feel embarrassed by it.

But that’s not always the impression I get when I look at the locavore movement, which is perhaps the most energized hunter-recruitment initiative happening right now. Unlike many efforts that focus on young hunters, this one targets an adult, often urban audience that didn’t grow up around hunting. But these folks have the disposable income to buy licenses and gear, and an interest in natural, locally sourced food. Going hunting seems to be a logical fit.

If a wild-game meal—or even a piece of deer jerky—sparks an interest in hunting for someone who didn’t have it before, then sign me up to help. But if I’m going to invest the time it takes to mentor, I need to know my efforts will do more than simply win a nonhunter’s approval. I want that person to actually go on to buy another license and hunt on his or her own. Right now, I think this effort is doing a good job of putting hunting in a positive light and getting quite a few people to try it. But I’m not convinced it’s converting people into long-term hunters in numbers that matter.

I don’t think the problem lies with the target audience so much as with the pitch we’re making. Some hunters seem to think that if we just fancy up our game cooking, hipsters will come running, eager to memorize the Ten Commandments of Firearm Safety.

From that, the first problem arises: a smug little hunting-foodie subculture. This movement’s philosophy seems to be that even a Manwich-eating hillbilly could be taught to consume venison correctly if only he’s shown the proper online recipe.

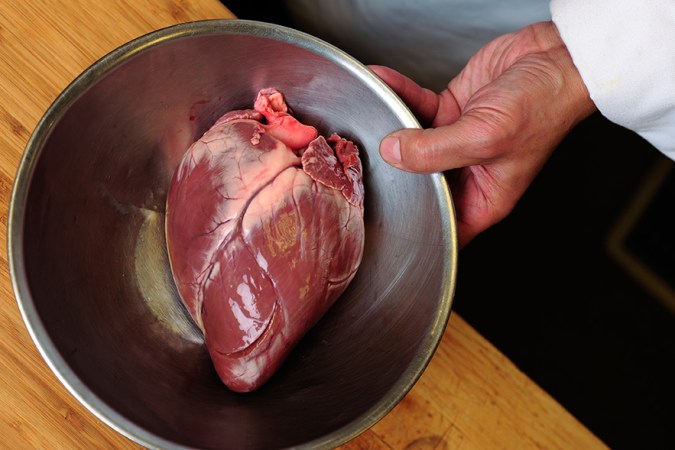

I think the 5-year-old who understands that deer are for dinner because they’re made of meat—not because venison is one stop on a voyage of gastric discovery—is learning pretty well. A lot of the folks doing that teaching are old-school veteran hunters who eat their venison with accoutrements like Italian dressing, bacon, and barbecue sauce. They think eating deer guts and buck testicles is weird and don’t care to listen to lectures on being “responsible carnivores” from former vegans. These hunters are also called upon to lend their time and expertise—and maybe their favorite stand on opening day—in the name of recruiting new hunters. For the locavore movement to truly take root in modern hunting culture, it can’t be off-putting to the veterans.

Still, the even bigger problem is simply that we’re selling the hunting experience short by focusing on the food. And that’s bound to fail. Yes, talking about the meal is an easy, sanitized way to justify hunting to a nonhunter. But we don’t need to justify anything. We’re recruiting, and we’d better start managing expectations for more than just a freezer full of meat or the promise of Instagram likes. Someone who’s motivated only by that is headed back to the farmers market after a couple of cold mornings on stand void of deer sightings.

We domesticated livestock to procure meat. Hunters would waste less time—and probably have more fun—by shooting an extra doe and gifting it to someone who wants to eat venison without appreciating the rest of it.

Truth is, a piece of backstrap sizzling in a dab of butter is a moment to appreciate, but it’s just that—a moment in the bigger story of the day. It’s not nearly enough to get me excited about waking up at 4 a.m. But the chance at getting the jitters from a buck walking into bow range or a turkey gobbling on the next ridge? That is. Those things are much tougher to define or explain than an exotic recipe. But the way I figure, cooking is easy. Getting meat is easy. Hunting is not. That’s why nobody tells stories about meals to their grandkids.