I bet some of your best hunting and fishing memories come from the very beginning. It’s true for me. I can recall every detail about the first deer I killed. I remember how that morning smelled—hot chocolate and burnt gun powder. My 20th deer? Not so much. Now if you read this website regularly, you know about the decline in hunter numbers and how it’s critical for us to recruit new people in order to preserve the future of our sport and fund the conservation of wild places. But these stories aren’t about that. These are about those first.

Memories are as close as you’ll get to your own first few magical seasons, but now as a veteran sportsman or -woman, you can recreate that same excitement, surprise, and joy for someone else. When you recruit someone new into hunting and fishing, it’s no longer just another deer or another fish. It’s the deer. It’s the fish. It’s a life-changing moment. It’s why you fell in love with hunting and fishing in the first place.

So we’ve compiled stories about our own successes and failures in converting new hunters and anglers. We hope you use these stories as inspiration, and then take someone new into the field and make some new memories of your own. Click here for tips on how to recruit new hunters and anglers. —Alex Robinson

Gridlocked: Some Urbanites Have the Will to Hunt, Even if the Way Isn’t Easy—or Conventional

By Natalie Krebs

When I moved to New York City to work for Outdoor Life, I was prepared to defend hunting. I was unprepared, however, for even casual acquaintances to ask if they could join me in the field sometime.

Sure, you can find anti-hunters, anti-gun activists, anti-you-name-its in NYC. But there’s also a rod and gun club full of the crustiest hunters I’ve ever met six blocks from my apartment, and a 100-yard archery range out by JFK airport where trad bowhunters from Queens and Brooklyn shoot every weekend.

Hunting itself isn’t trendy in the city. Or at least, it isn’t yet. But the field-to-table movement is, and for all the right reasons: natural food, locally produced and sustainably sourced. Where this trend intersects with urbanites’ existing outdoor interests—cooking, camping, that new spot in Manhattan offering archery lessons—there’s fertile ground for growing new hunters.

So last year, I decided to see who among my friends was really game to try hunting. By summer’s end, five friends had taken hunter’s education (a scheduling nightmare here) and I was sick of coordinating. So I stopped talking about hunting and waited to see who would rekindle the conversation.

Two of them did: my boyfriend, Arc, and his buddy Nik. Both guys are in their early 30s and live in the city for their jobs, just as I do.

Nik was browsing Netflix a year ago when he stumbled upon the series MeatEater. The cooking segments appealed to him, as did the episodes where host Steve Rinella didn’t fill a tag. After watching enough episodes, Nik thought, I have to try this.

Arc is a mechanical engineer by training and a cheap bastard at heart. He’s also an obsessive do-it-yourselfer who likes to take things apart, learn how they work, and rebuild them, sometimes better than before. He spends his vacations backpacking in the wilderness and has always wanted to learn how to butcher game. He was already a hunter—he just didn’t know it yet.

One of our earliest dates involved me lugging a cooler of venison quarters to his Manhattan apartment and commandeering his vacuum sealer, which he owned to package fridge-aged bargain beef steaks before sous-viding them in a mop bucket. I told him about what had been a gut-twisting bowhunt and my best blood-trailing job yet. He listened to the story patiently, then asked how much meat I’d brought back.

So in February, I called in some favors and weaseled the three of us into a winter rabbit hunt upstate.

We spent a Friday driving out of the city, reacquainting the guys with shotguns, and talking through the logistics of the following day. We’d be tagging along with a crew of veteran hunters and their beagles.

After the first flush, we all stop worrying about whether the new guys would hit rabbits. Arc makes a quick killing shot, and Nik follows up with the second. Despite the sub-zero temps, we kick up two dozen bunnies.

Still, it’s not an immediate conversion. I hear vocabulary like “harvest” and “take down” instead of “shoot” or “kill.”

But it starts to click for Arc. Halfway through the first morning, he mouths at me from a few yards down the line: This is fun. He spends an inordinate amount of time admiring each dead rabbit; I can’t tell if he’s curious or feels obligated to clock a certain number of minutes respecting each animal before stuffing it into his game vest.

Nik is more stoic. He politely declines taking a pic beside a row of dead rabbits and our shotguns. I know the research—many new, food-focused hunters disapprove of the classic grip-and-grin photos—but forget about it in my excitement.

It strikes me, not for the first time, that my friends will never sound or act like most hunters I know. But that doesn’t matter. It’s not my job to define how they hunt, just to give them a chance to see what it’s all about. Their interest in the meat got them here. I’m hoping the hunting itself will bring them back. When it’s time to clean rabbits, they learn by example and then tackle the rest, becoming efficient butchers as they work at the tailgate and swig bottles of beer.

On day two, we push through thicker cover and wear out by noon, at which point we call it a day and load up, but not before agreeing to do this again over a round of hearty handshakes. Everyone is welcome back. I consider this the last test of the season for my friends, and they have passed.

Initiation: The Making of a Deer Hunter

By Alex Robinson

We’re busted again. Fru Louis points at the flash of a white tail flagging through the brush and whispers excitedly, “There’s a deer.”

More accurately, it was a deer. Now it’s just the sound of branches snapping and alarm snorts. My new hunting parter is unfazed, but I grind my teeth a little. Things are not going as planned.

Fru is a 30-year-old software engineer who immigrated to the U.S. from Cameroon when he was a young kid. Now he and I are sitting in a natural ground blind along a flooded riverbottom in the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge, on the first morning of a state-sanctioned mentored deer-hunt program. So far, Fru and I have managed to blow out every whitetail in the area.

We had scouted this spot two weeks before, when the water was even higher. I met up with Fru in the parking lot of a baseball field that bordered the refuge and handed him a pair of waders. “Welcome to deer hunting on public land,” I told him. But he was undeterred.

“I’m ready for an adventure,” Fru replied, so off we went.

The Minnesota River had come up fast in the weeks prior, and the area we were allowed to hunt was now flooded timber. It was the first time that either Fru or I had been to this spot. As we waded down the trail, hoping to find high ground, Fru told me why he had signed up for the DNR mentored hunt program in the first place.

Back home in Cameroon, Fru’s dad was a hardcore outdoorsman, and Fru grew up eating bush meat from the critters that his dad trapped and hunted. When Fru’s dad came to visit the U.S., he was amazed by the game numbers and the amount of sign he saw while hiking around the woods. He coaxed his kid: “You’ve got to get into hunting here.”

I’d started to tell Fru about how my dad taught me to deer hunt when I was young, and how we’ve hunted together at the same deer camp every fall since I was 12, but I cut the story short when we bumped into some dry ground with a muddy deer trail running through it. We were about a mile from the parking lot. This was the spot, and we hustled to build a makeshift blind before sunset.

On our slog back, we heard a barred owl call for its mate, and Fru’s eyes lit up like lightning. Scouting mission accomplished.

Read Next: 21 Ways to Recruit New People into Hunting and Fishing

WAITING, HOPING

But now, halfway through the morning, it seems like that first-hunt enchantment is wearing off. A few hundred yards away, there’s a duck hunter wailing on a mallard call like he’s signaling for rescue, the deer are gone, the sun is high, and Fru is getting fidgety.

We manage to make it to noon before we hike out and meet the others in our group for lunch. Our crew of brand-new hunters ranges in age from early 20s to mid-60s, about half live in the Twin Cities, and about half are women. The state’s goal is to recruit new adult hunters, and if those new hunters have different backgrounds and life experiences, even better. The limiting factor for this program? Finding enough qualified mentors to pair with the hunters.

The newbies have been through firearms safety, three classroom sessions that cover the basics of deer hunting and butchering, and instruction at the shooting range. They’ve done their part; now it’s up to us—the volunteer guides—to show them what deer hunting is all about. But over cheeseburgers and fries, we find out that Fru and I are the only ones who’ve seen deer.

During the first classroom meeting, each student described why he or she wanted to learn to hunt. All of them mentioned “the meat” as a primary reason.

I liked this. Simple and pure. What I hadn’t anticipated, though, was the pressure I’d feel to help Fru get his deer. He’s in it for the meat, so I would be too. But there is much more to it. The reasons for hunting and killing a wild animal run deeper than a pair of backstraps. Veteran hunters feel it down to their core. I want Fru to feel it too, or at least get a taste of it. But experienced hunters also know that this thing cannot be communicated so easily with words. So, I save my speech about how hunting is humanity’s last real connection to nature. Instead, I just ask Fru if he’s ready to go out and try again. He grins and nods.

SMALL MIRACLES

After an eventless afternoon sit, we are back at our spot in the marsh early the next morning, this time with a pop-up ground blind. It’s all quiet when the sun comes up—our duck-hunting buddy is gone. And then, remarkably, a young buck appears to the right of the blind, just 40 yards away. Fru spots it first, and this time instead of pointing, he reaches for the gun. The buck is quartering away, and when I see that Fru has his gun up, I hit my grunt tube to stop the deer and whisper, “Shoot him.”

The gun goes off, and the deer disappears into the marsh grass. I give Fru a tentative pat on the back and tell him we’re going to wait a little before tracking the buck—and I pray to the deer gods that the hit was good. I try to text our program leader that we’ve shot a deer, but my hands are shaking, so I just put the phone down and soak it in. Fru’s smiling wide like he just got off a roller coaster, repeating, “Oh my goodness, oh my goodness,” over and over.

What comes next are the customs any deer hunter will appreciate. A short blood trail and a quick photo session. A careful gutting job, a sweaty drag, a retelling of the story to every hunter in our group, and, finally, cold beers and butchery back in the garage.

Once we’ve got the deer quartered, I persuade Fru to cut the rack off the little buck. He doesn’t understand why anyone would want to save the antlers from an animal, but he listens to my last advice of the hunt: “Someday, when all the meat is gone, you’re going to be glad you have those antlers.”

Just before I leave, Fru clears off a spot on his workbench and carefully props up the rack.

Reel Talk: Creating New Anglers Isn’t All Trophy Photos and Glory

By Joe Cermele

I’ve caught a lot of fish in a lot of places. None were more special than my daughter’s first bluegill, and it keeps getting better. Seeing her excitement every time that bobber dips and watching her marvel at the colors of each tiny panfish calms me like a stiff drink.

Conversely, taking an inexperienced adult fishing conjures the same pit-of-the-stomach fears as a public speaking class. I would like to say that I’ve turned countless rookies into diehards in all my years on the water (maybe I have flipped a switch or two through my writing), but one-on-one, I’ve not flipped any. This is partly because I surround myself with anglers. Most of my closest friends fish hard. My list of non-fishy friends is short, and no one on it has ever asked to go.

I’m not going to beg. I think it’s important that newbies want to go fishing without being pushed by a veteran angler.

Take my younger cousin, Nick, for example. He put up a 35-pound striper on his first (and last) time on my boat. He got the photo. He was thrilled. But that was it. There was no fire to go fishing again.

Converting new adult anglers isn’t as easy as taking them to a bluegill pond. In our “I want it now” society, not many people are interested in starting from scratch. Their interest in fishing is based on your experience, which means they want to catch the same stripers, big bass, muskies, and trout that you’re posting on Instagram. The goal is to get them to come back again and again. If a newbie gets the impression that it could take many trips of bluegills and basics just to build up to the fish they really crave, they probably won’t come back at all.

So instead, you throw them right into the fire on the first outing. Skip chasing the schoolies in the bay or nymphing little rainbows, and go for the 40-pound striper or giant brown trout they dream about.

You, of course, are well-versed in what it takes to achieve those Instagram-worthy fish. You’ve suffered through skunks and bad weather, and you’ve spent years learning the right spots. So, let them see what it really takes. If they embrace the effort and skill that go into the pursuit, then they’ve got a real chance to make it as an angler. If they seem bored while stripping big streamers to just move two or three high-caliber trout, or they get cranky slogging 15 miles in a chop to reach heavier stripers, well, there’s a strong possibility that they’re not cut out for serious fishing.

Rookies will always tell you they understand there’s no guarantee of catching fish. That’s a lie. They’ve been dreaming of their trophy fish photo since the day the big trip was planned, which is why I get so tightly wound when I’m taking someone new.

They coast on visions of glory until go time; meanwhile, I’m mired in worry about the weather, the wind, and the bite. I’m obsessing over plans A through F. So I try to avoid setting a firm date. I always tell a new person to keep a week or weekend open, and we’ll pick the day when it gets closer. Sometimes that works; other times life, family, or work simply won’t allow it and you end up playing the hand you’re dealt.

The philosopher-outdoorsman would say it’s not about the catch, it’s about the experience—just being on the water. I don’t disagree, but I believe that mentality only takes hold over time. Catching on the first trip is critical. Sorry, but it’s true. If you give the right rookie something to cling to during that first experience that gets him pumped to go out again, he’ll learn to appreciate just being there on the tough days. He’ll remember how good it can be, and he’ll want to re-create that high.

Deep down, I think we all want to be mentors. Part of the reason I got into outdoor writing is because I love teaching people to fish and sharing the knowledge I’ve gleaned from hundreds of other expert anglers. The irony is that I’m sharing that knowledge with people who already fish.

Time on the water is precious, my own included. So, I’m ready and willing to help the right person build the same level of passion that I have for fishing, but I’ll only do so if I feel their interest is genuine.

Until I find them, or they find me, I’ll be at the bluegill pond with my kids, anticipating that day when they’re ready to head offshore or to trophy-trout water.

Coming of Age: A New Hunter Finds Direction From Behind His Grandfather’s Rifle

By Andrew McKean

Gerald Giebink is 23 years old, and he has no idea what to do next. He just graduated from college in his hometown of Billings, Montana, and he’s been unable to land a job for the worst and most universal reason: prospective employers tell him he’s inexperienced, but they won’t give him the chance to get the experience they require. He’s living back at his parents’ house, taking shifts at Home Depot for spending money, and restlessly planning for a future that doesn’t have a clear place for him.

Maybe that’s what made him ripe for a news release I distributed to Montana newspapers last year. It was an invitation from my local sportsman’s club for beginning hunters in my part of the state to match up with an experienced mentor—someone to take them out in the field, show them the ways and means of hunting, and assist in the collection and butchering of wild meat.

Gerald’s first communication with me was uncomfortably candid. He had never hunted, he said, because he didn’t have anyone to take him. His grandfather had always told Gerald that he’d mentor him, but the grandfather had died, leaving Gerald his Browning rifle, his Buck knife, and an unfulfilled desire to hunt.

“I’ll take you,” I told Gerald. What I didn’t tell him: If someone is so eager to learn to hunt that he would call a random number in the newspaper, then I won’t be the one to not take him hunting. If I had any questions about Gerald’s commitment to this cause, they were answered when he bought a ticket on the little turboprop commuter plane that flies between Billings and my town. I picked him up at the airport, his grandfather’s .300 WSM in a case and a daypack over his shoulder.

Learning to Crawl

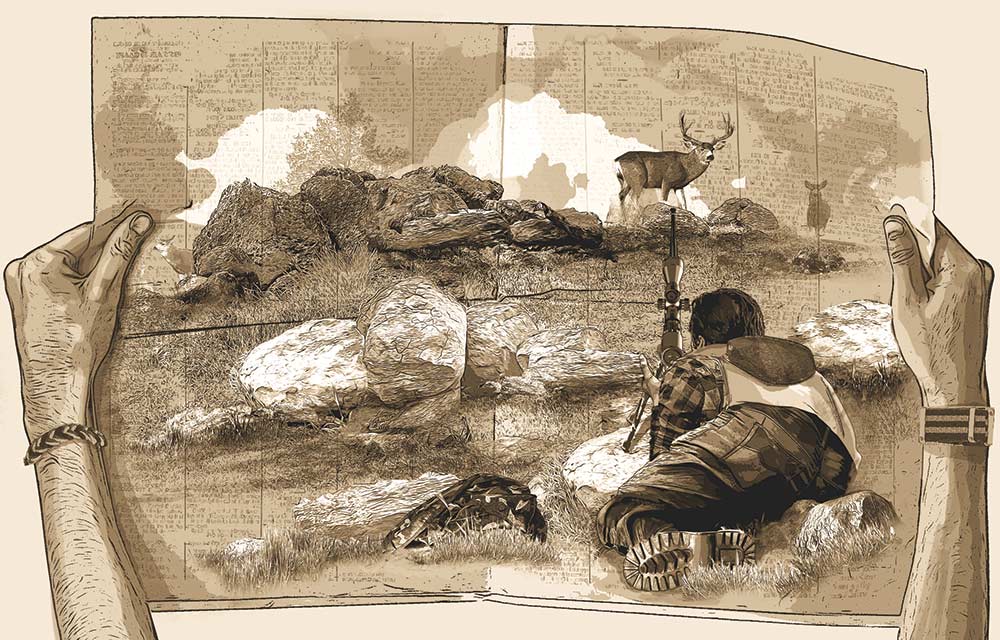

Hunting is equal parts art and science. The science is knowable and largely repeatable. Knowing where your bullet will hit at 400 yards. That’s science. So is calculating how far away a mule deer will see a silhouetted human on a prairie skyline. Belly-crawling through sticky gumbo? That’s art. Waiting is art too, whether you’re waiting on a whitetail to turn broadside for a clean shot or abiding years to experience just such a moment. Art is changeable. And utterly unrepeatable.

It’s this mixing of the two, the knowable and the unknowable, that holds the magic of hunting for me. But the art is hard to explain to someone who has never hunted, so our first days in the field were all about the science. And it turns out, Gerald has an uncanny ability to judge distance and detect animals, and to reach conclusions based on the available evidence.

At one point, after a difficult creek crossing during which Gerald had to pull himself up the steep bank using willow saplings for purchase, he asked to stop to catch his breath and scrape heavy mud off his boots.

“I have to get in better shape,” he told me, a little sheepishly. “I want to be able to take my buddies hunting, and they’re going to count on me to be in charge. I can’t lead from behind.”

That’s when it hit me. Sure, Gerald was interested in obtaining venison for his family and proving his capability in the field. But what he really wanted was confirmation that he was the rightful heir to his grandfather’s legacy. I realized that a successful hunt might move him out of the post-college crossroads funk and toward a new identity. And I realized that although Gerald had never hunted, he defined himself as a hunter. Even more, I began to see that Gerald is a mentor by nature, but he was understudying with me as a way to log time and experience in order to grow confident in the role.

With my realizations came responsibility. For better or worse, a beginning hunter’s value is measured by success, and I knew Gerald needed an animal not only to certify the experience, but also to serve as a passport to his future identity.

On my home hunting grounds, I can usually conjure a deer at any given time, and because Gerald didn’t care if it was a buck or a doe, I figured we’d be moving on to the gutting and skinning part of his tutorial before long. Only we couldn’t buy a shot. The deer were skittish and veered long, or they were in range but running. We arrived at our final morning together deerless. The wind was wrong, but there was a place we could set up and hope that mule deer might move toward us. If we could make a shot before the deer got dead downwind, we might be able to score.

An Old Rifle Makes Meat

The first thing we did when Gerald arrived in my town was go to the shooting range. I wanted to see him shoot, to assess his gun-safety skills but also the capabilities of his rifle and his aim. His gun was off by 18 inches at 100 yards, but shot by shot we got him on paper, and then in the bull’s-eye. Eventually, he printed a decent group at 200 yards, which I reckoned to be his maximum effective range. As we sat together that final morning, the wind at our backs and the cold creeping into our clothes, I had Gerald dry-fire at bushes and fence posts. He was dead-calm, and his barrel didn’t so much as twitch as he pulled the trigger. When legal light arrived, he chambered a shell and waited.

An hour later, a young muley buck jumped the fence from the neighbor’s land, pushed a doe, and then turned toward us. I ranged him at a little over 200 yards.

“Wait until he turns broadside,” I whispered. “Hold halfway up his body, just behind his shoulder. Shoot when you’re…”

The muzzle blast took my words. The bullet took the buck.

Art. Science. Graduation.

If I were to distill the essence of satisfaction in the field down to a single image, it’s the picture of Gerald, holding his grandfather’s Buck 110 knife and making the first, tentative slice into the belly of the still-warm buck, cutting a clean path to the vitals.

Read Next: Why We are Losing Hunters and How to Fix It

How to Get in the Game

The National Shooting Sports Foundation has created an online guide that’s jam-packed with great info for aspiring mentors. The goal is to get experienced hunters and shooters to each bring one new person into the field this year. Join the Plus One Movement at nssf.org/plusone.