The size and diversity of the waters we call “The Great Lakes” boggles the mind. This system contains 21 percent of the world’s fresh water supply and has 160 native species of fish, supplemented by many imports, arriving via stocking trucks and otherwise. Though they’re connected hydrologically, each basin is unique. In fact, a biologist recently told me the only thing that Lake Superior and Lake Michigan have in common is they both contain water.

Since anglers began to wrestle its bounty from commercial fishers in the early 20th century, its popularity as a sporting destination has grown, now estimated at over $1.2 billion in direct annual angler expenditures. Its economic impacts are far greater, not to mention historical significance and sociological attributes. But it’s not been an easy journey.

With many international ports, the Great Lakes have been a dumping ground for exotic creatures that crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the ballast water of freighters. The latest count lists 25 fish imports, 59 plant species, 24 algae, and 14 invasive mollusks. A few have been benign or possibly even beneficial. Others have threatened the entire ecosystem, most notably zebra and quagga mussels. Yet in the face of these assaults, the Great Lakes still deserve their name.

I credit their resiliency to the cohesion of aquatic systems and the leveling power of nature, coupled with the impressive efforts of state biologists and management agencies to help fishing thrive. They’ve learned to deal with fluctuating nutrient dynamics, which lie at the heart of aquatic ecosystems. While salmon fishing will never return to what it was in the 1980s, and perch have suffered an overall decline, steelhead, bass, walleyes, and muskies have never been better. And several exciting gamefish species have come onto the scene. The future fishing outlook for the Great Lakes is indeed bright.

Along the shores of the Great Lakes lie 32 cities with many tens of millions of potential anglers living within a short drive of its waters. And scattered along its shoreline, in communities large and small, are thousands of fishing guides who can dial in the bite at any time of year. No matter which species you’re after, you won’t be disappointed.

Lake Superior

The largest and deepest lake (483-foot average depth) hosts a wide array of gamefish and many populations are flourishing. The rehabilitation of lake trout is the headliner, one of the biggest fisheries management success stories of recent decades. It was accomplished by water pollution controls and an aggressive campaign to destroy sea lampreys by treating tributary streams with the piscicide TFM to kill larvae.

“The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) stopped stocking lakers in 2015,” says Cory Goldsworthy, fishery biologist stationed at the Duluth office. “Natural reproduction has been strong, with good growth on a diet of mostly smelt. We’ve sampled fish as old as 40. It’s a diverse sport fishery, with charter captains working the North Shore, as well as shore, ice, and small-boat anglers. Jigging and trolling are very effective, targeting lakers that roam shallow in spring and fall, and into the 100-foot range in summer.

“We also have a self-sustaining population of steelhead that provides a great spring fishery in tributaries for fly and bait fishermen, as fish run 5 to 7 pounds. It’s been catch-and release for wild fish since 1996. Wild populations of coho and Chinook salmon provide good offshore trolling action; and cohos run the shoreline from December through March, accessible to anglers with small boats.”

Another special treat for anglers in western Lake Superior are beautiful “coaster” brook trout, which follow an anadromous lifestyle in the big lake. Naturally reproducing, they’ve thrived under a 20-inch minimum length limit. On Wisconsin’s side of the lake, several bays, including Chequamegon, offer trophy smallmouth bass, governed by a 22-inch minimum-length limit, and more big pike are showing up. Wisconsin guide Chris Beeksma reports that yellow perch are on the upswing as well.

“We’re finding good numbers of fish from 10 to 12 inches all over the western part of the lake,” Beeksma says. “The Wisconsin DNR has been stocking Seeforellen brown trout since 2011. They’re growing fast, and trophy fish over 20 pounds are showing up. We have excellent ice fishing for them in about 10 to 20 feet, as well as a good nearshore bite. They don’t seem to wander out into the abyss like salmon.”

Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan has hosted excellent offshore fisheries for salmon and steelhead since these West Coast species were introduced in 1966. In recent years, though, state and federal fishery managers have struggled to balance numbers of preyfish–primarily bloater chubs and alewives, deepwater sculpin, and smelt–with stocking levels of salmonid predators, including brown trout, which have anchored a very popular near-shore fishery for giants over 20 pounds. The invasion of zebra and quagga mussels drastically cut levels of plankton, clearing the water, but also sequestering nutrients needed to fuel the food web. As a result, pelagic preyfish like alewives, the favorite food of salmon and steelhead, have dwindled.

Adding to the challenges is that the waters of Lake Michigan vary in fertility. Mark Romanack, host of 411 Fishing TV, show notes that Michigan waters are less fertile than on the Wisconsin side.

“That affects preyfish numbers,” he says. “State agencies use those estimates to plan stocking density, so Michigan DNR has reduced stocked salmon, steelhead, and brown trout, resulting in drops in angler catch rates.”

The good news is that the Wisconsin DNR is boosting stocking levels in their waters from 2020 to 2022, increasing salmon numbers 48 percent; steelhead 31 percent; and brown trout to 450,000, a 20-percent boost, based on a recent upturn in preyfish. This promises good stream and offshore action over the next couple of years.

Green Bay, a massive embayment on the lake’s west shore, is shallow and fertile, and offers some of the best smallmouth bass and muskie fishing in the country.

“We catch quite a few giants from 50 to 54 inches,” reports Bret Alexander, a long-time, all-season guide based in Green Bay. “They’re stocked by Wisconsin DNR and grow fast on gizzard shad and other preyfish. Our best bite gets going in July and lasts into November. We have lots of muskies in the 40-inch range, so prospects are great for future glory.”

Smallmouth bass abound in the Sturgeon Bay region of this vast bay. “There are loads of 5- and 6-pounders,” Alexander adds, “and fish from 7 to 8 pounds aren’t rare. They start going in May; and June and July are outstanding. It’s so clear over there that we can sight-fish for feeding bass throughout the season.” Other smaller bays near Green Bay also offer excellent opportunities for walleyes and smallmouth bass, notably Big and Little Bays de Noc.

Alexander has also established an ultra-popular winter fishery for lake whitefish. “At times we have 300 people out there on weekends, lots from Chicago, but all over as well. They bite small baits set on dropshot rigs; you mark fish on sonar all day.” These silvery beauties run 1 to 3 pounds and are fun on light tackle and excellent smoked, fried, or baked. Lake Michigan’s fisheries have shifted over the last decade, but outstanding opportunities remain across its waters.

Lake Huron

Lakes Michigan and Huron could be lumped together from a technical standpoint, since they represent one basin that’s squeezed through a 5-mile wide channel, the Strait of Mackinac. But their basins and topography differ greatly, and has been altered greatly by the influx of exotic species, both before and after zebra and quagga mussels that arrived in the late 1980s. Due to altered nutrient pathways, abundance of pelagic baitfish has declined. Alewives, favored prey of Chinook salmon virtually disappeared from Saginaw Bay, a vast waterbody (1,143 square miles) on the east side of the state of Michigan, early in the 21st century.

Alewife decline and invasive round gobies (a favored prey of many species) fueled a walleye resurgence, particularly since alewives feed on larvae of walleyes and other species. Dave Fielder, Research Biologist with the Michigan DNR, stationed at Alpena, says, “We stopped stocking walleyes in 2006 and they’re at an all-time high, fueled by several strong year-classes. It’s a diverse fishery—casting, trolling, jigging—as well as an increasingly popular ice fishery. And there’s a strong run up the Tittabawassee River. We have an eight-fish daily limit and 13-inch size limit, a rare regulation in walleye fisheries today. Saginaw Bay also offers an excellent smallmouth fishery along its many rocky shorelines.”

Fishing remains solid in the lake itself, as the Michigan DNR has been planting more Atlantic salmon lately, a species with a more diverse diet than Chinooks, while coho and Chinook remain at reduced numbers. A strong population of steelhead exists, providing offshore and stream opportunities, supported by stocking and natural reproduction. And as in other Great Lakes, lake trout are thriving.

“We have an excellent small-boat lake-trout fishery in 30 to 60 feet north of Alpena,” says Fielder. “Without alewives in their diet, lakers are far less oily and better tablefare.”

Georgian Bay represents yet another key embayment of Lake Huron, extending northeast into Ontario. It’s 120 miles long and 50 wide, with areas of rocky shoals as well as sandy beaches. A popular tourist destination, you find some 30,000 islands and many small lodges nestled along shorelines of rock and piney forests. Big muskies are a draw, with giants coming in open waters and feeder rivers. Big pike, walleyes, and largemouth and smallmouth bass add space to this fishery. As with Lake St. Clair, lying between Lake Huron and Lake Erie, it’s sometimes been labeled the “Sixth Great Lake.”

As waters depart Huron via the St. Mary’s River, they form Lake St. Clair, a prime fishery in itself, one of the most popular locales for top-level bass tournaments due to its vast numbers of big smallmouths. It also has one of the country’s best muskie populations, boasting catch rates over a fish per day—unheard of in most waters. Trolling and casting work across its mid-depth flats with patches of vegetation and sand. And the Detroit River, flowing from St. Clair to Erie past Detroit, is home to deepwater giants.

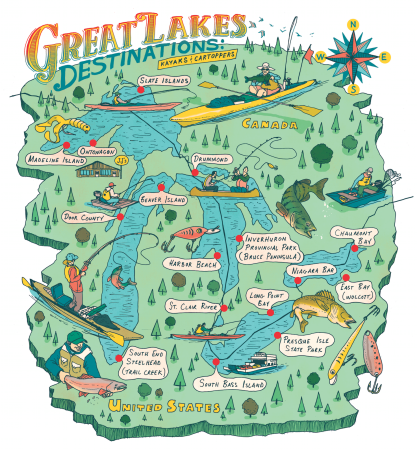

Read Next: The 26 Best Places to Fish on the Great Lakes

Lake Erie

Walleye are booming on the smallest Great Lake. Jason Robinson, Lake Erie Research Unit Leader with the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) calls it, “A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” for walleye anglers throughout Erie. And the outlook looks even brighter.

“Catch rates are near three to four fish an hour,” he says, “three times higher than earlier years. Estimates for the lake are about 116 million adults, with 121 million expected in 2021. We’ll have outstanding fishing for over a decade, as walleyes live long and keep growing.”

Smallmouths are going strong from one end of the lake to the other as well, while yellow perch also are thriving. “Walleyes, bass, and perch are all spawned naturally,” Robinson says. “Smallmouth catch rates are about a fish per hour, which is about as good as anywhere in the U.S. and we have our share of trophy-size fish, while perch average about 11 inches.”

Like walleyes, steelhead are booming in Erie, offering anglers cold water and warm water options. Jim Markham, senior coldwater specialist at DEC, reports that New York plants some 1.8 million steelhead yearlings a year, while other states add to that total, and returns have been spectacular.

“Folks are catching 40 to 50 fish a day, working 30 to 40 feet of water out west of here,” Markham says. “While it’s mostly stream fishing in this region, which begins in late September and may last through winter. Cataraugus Creek is steelhead central here.”

Over in Ohio, Travis Hartman, Lake Erie Program Administrator for Ohio DNR, also celebrates the walleye boom, adding that abundant smelt in the Central Basin keep steelhead well fed. “We have a large group of dedicated stream steelhead anglers in Ohio,” he says, “who fish the tributaries between Vermilion and Conneaut Creek. You can catch fish by fly fishing, casting lures, or floating egg sacs, as well as out in open water. Catch-rates are off the hook, compared to traditional fisheries elsewhere on the Great Lakes and West Coast.

“Smallmouth numbers are lower than in the 1990s, but still outstanding, as we have catch rates near a fish per hour. But the big news is the expansion of the largemouth population, which began in shallow harbors like Sandusky and East and West Bays. But folks are catching them out in the lake, around the Bass Islands and other shallow structures. Catch rates are a good bit higher than for smallies.”

As Erie’s waters exit, they pass through the Upper Niagara River near Buffalo, New York. This section has become a top location for big muskies, particularly in fall according to Mike Todd of DEC. “The nastier the weather, the better the big ones bite,” he says. “Fishing for smallmouths and walleyes also is excellent above the Falls, and there’s a population of nice largemouths, too.”

Lake Ontario

Below Niagara Falls, anglers enjoy the bounty of the Lower Niagara as it flows into Lake Ontario. Captain Frank Campbell has patrolled this section of the river, as well as Lake Erie and Ontario for 30 years.

“This river offers outstanding fishing for lake trout, as you drift downstream,” he says. “But we’ve been catching big brown trout, including my personal best, a 31-pounder! Browns move into the river in fall and stay the winter. It’s a 12-month fishery on the Lower Niagara, as we have lots of steelhead, and smallmouths join the party in May.”

Ontario also features strong steelhead runs in its tributaries, notably the Salmon River, 18 Mile, Sandy, and Oak Orchard creeks. They also host a run of Chinooks in early fall, with steelies coming later and remaining for months. Chris LeGaard of the DEC notes that creel surveys show the highest catch rates for Chinook out in the lake during the last couple of years.

“We still have good numbers of alewives, so the salmon have been thriving, though we’ve reduced stocking numbers to balance preyfish abundance, but we also have a lot of natural reproduction,” he says. “We’re at a good place now. Anglers appreciate the diversity of our coldwater fishery, has you may catch 4 or 5 species on a given day, with lots of big fish.

At the east end, near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, a series of shallow bays in northwestern New York—Henderson and Sackets harbors, Mexico Bay, and others—offer prime rock/sand habitat for smallmouths grown fat on gobies. The 1,000 Islands area of the St. Lawrence is yet another incredible trophy-smallmouth bass zone, and quieter bays house big largemouths, as well. Record-size muskies also patrol the deep currents of the river, where hardy souls trolling giant crankbaits in late fall are rewarded.