Across nearly all of the Eastern wild turkey’s range, its story is one of loss and recovery, of the wildly successful reintroduction of an iconic species that was simply gone for generations.

But there’s one place that never lost its turkeys: the steep white-oak ridges and plunging limestone hollers of Missouri’s Ozarks. The turkeys remained for the same reason that hunting them here is so challenging: because the country is huge and rugged, and the birds, their senses sharpened by more than two hundred years of uninterrupted hunting pressure, are diabolically smart and evasive.

It’s here along the forks of the Current River, where the few remaining wild turkeys were discovered in the middle of the last century, that biologists perfected the practice of baiting and net-gunning, capturing wild turkeys that were then stuffed into transport boxes and released in unpopulated habitat from Ontario to Kansas. So if there’s a motherland for America’s wild turkey, this is it, which is why I found myself here, huffing up a lung, scrambling to the top of a steep, moss-slick ridge to engage with a gobbler that had been singing since sunup.

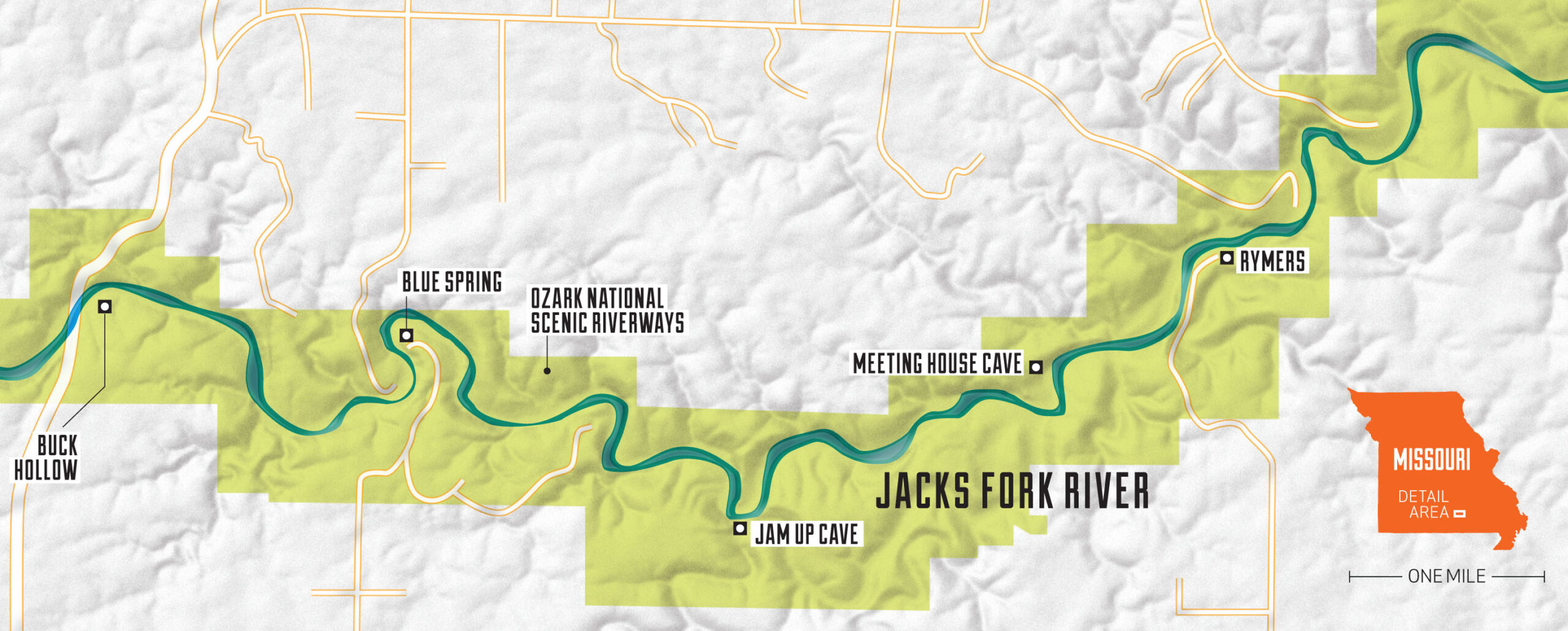

I had joined my friends from the National Wild Turkey Federation and the Missouri Department of Conservation on the Jacks Fork of the Current River to hunt birds in a place that has always heard the thunder of a spring gobbler. This turkey homeland is made up almost entirely of public ground, and because a river runs through the middle of it, it is suited to a unique style of hunting. We would launch our canoes at dawn, paddle and float downstream until we heard a gobbler, and then beach our boats and figure out how to kill him.

On our first morning, we hadn’t been in our canoes more than 20 minutes when we heard the first gobble. We strained up a ridge, set up just over the crest, and called a lone tom right to my shotgun. I missed that shot and have played it over and over in my mind because that was the last turkey we called into range. For the next three days, we floated and called and hiked thousands of acres of the Ozarks. We worked several different birds, but never got the satisfaction of canoing with a dead tom in the bow.

Wild and Scenic

Despite a lack of birds, I’d recommend this hunt to anyone willing to work for a tall-timber tom on public land. The stretch of the Jacks Fork we hunted is within the Ozark National Scenic Riverways corridor, which is managed by the National Park Service and bordered by tens of thousands of acres of state and federal recreation lands. That means the land above the river is nearly all public, so if you hear a gobbler, there’s a good chance that you can make a play for him without having to worry about trespassing.

Camp at established sites, and float as far as you want in a day. Fish when you’re not hunting. Because each day of Missouri’s spring turkey season ends at 1 p.m., we spent the afternoons casting to scrappy smallmouth bass and exploring riverside caves and springs.

FROM THE OZARKS TO EVERYWHERE

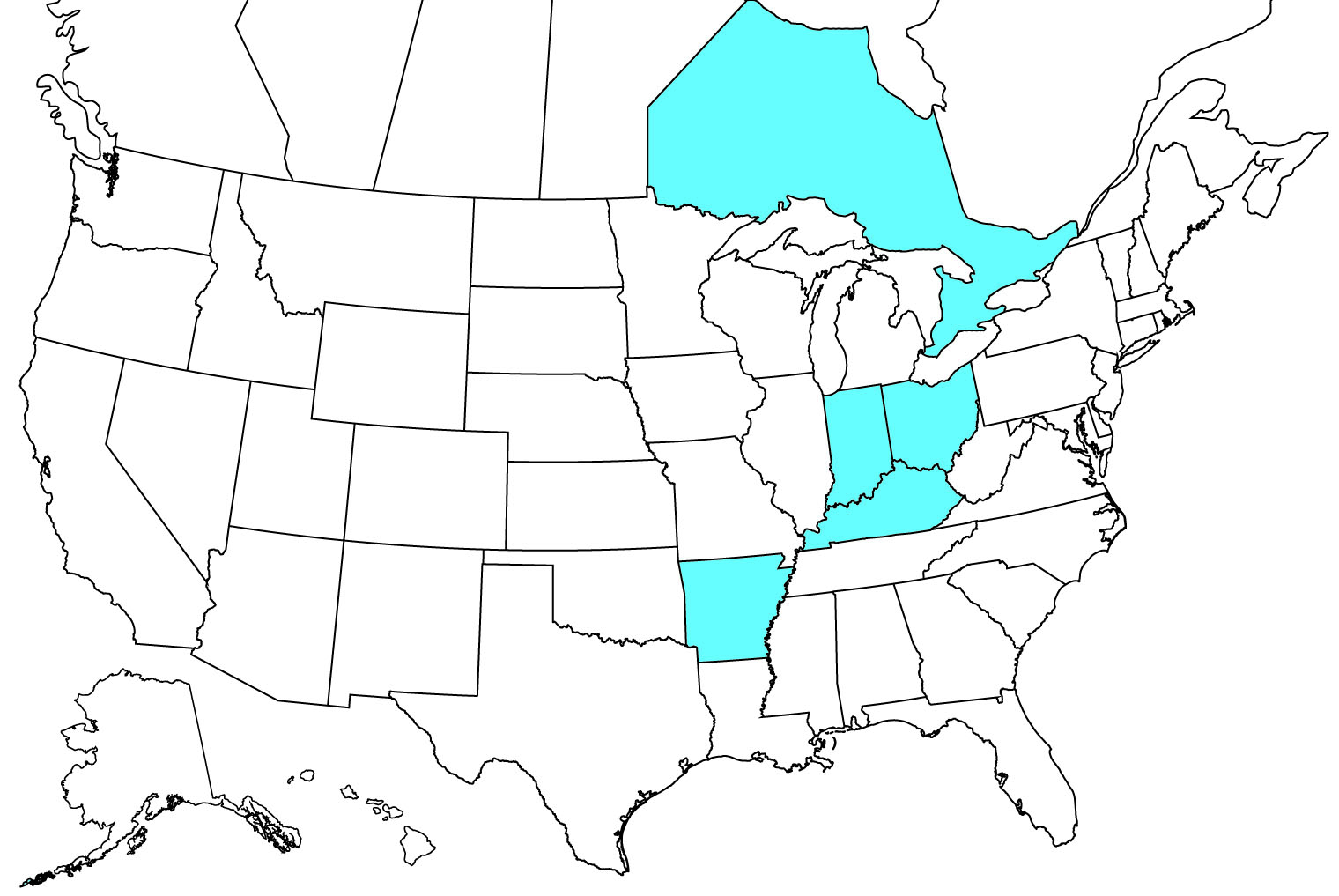

According to records kept by the Missouri Department of Conservation, more than 5,000 Eastern wild turkeys that were trapped in Missouri have been translocated to other states and provinces. They are the seed stock for flocks that have grown to number in the tens of thousands. The translocation program started in 1958 with a single turkey trapped in southern Missouri and released in Ohio.

The transplant operation culminated in 1984, when nearly 900 Missouri turkeys were released in Kentucky, Arkansas, Indiana, and Ontario.

Most of the state’s birds were trapped in the remote hills around the Current, Jacks Fork, and Elevenpoint rivers. This habitat is now the focus of a new restoration effort. Kentucky, a state that benefited from Missouri’s turkey largesse, has given elk to the Show-Me State, and the biggest release area is just southeast of the Jacks Fork. Soon, canoeing hunters may have the chance to chase bugling bulls across the ridges and limestone hollers of the Ozarks.

IF YOU GO

Timing

We hunted near the end of Missouri’s three-week season, so the birds we encountered had already heard plenty of hunters’ calls. It’s probably best to hunt early—this year the season opens April 20—and be prepared for sketchy weather in order to hunt relatively unpressured toms.

Boating

The Jacks Fork’s flow is controlled by natural springs at its headwaters, but it can run high following rains. Your paddling skills must be sharp; pack all your gear in dry bags, because the odds of tipping a canoe are pretty good.

Fishing

The smallmouth density in these spring-fed rivers is remarkably high, but the spring-clear water puts a premium on lure choice and presentation. Downsize your gear, and use pinpoint casts and drift-free floats with small tube jigs and creature baits, or twitch shallow-running hard-body baits. The biggest and best fish hang around submerged timber, so expect to snag up and lose plenty of tackle to the river.

Permits

Float permits and reservations are not required for recreational floating or hunting. Visit the National Park Service’s site for details, maps, and restrictions.

Campsites

Established tent and trailer campsites cost $14 per night, or you can camp in an unimproved backcountry site (as we did) for $5 per night.

Canoe Rental

If you can’t bring your own canoe and float gear, not to worry. At least a dozen concessions offer rentals. We used Harvey’s Alley Spring Canoe Rental (888-963-5628; harveysalleyspring.com)