Editor’s Note: This is part two of a three-part series on trophy hunting in Africa. See part one here.

As a youngster in the middle of the last century, leaving his native Germany for a home in Namibia he had never seen, Volker Grellmann dreamt of the animals he would encounter. Ferocious cats, colossal rhinos and elephants, antelope of every stripe of the hide and curl of the horn.

When he arrived in South West Africa–Namibia’s name at the time–Grellmann was dismayed to find a relatively sterile landscape. Sure, there were cows and sheep, just as in his native Germany, but few specimens of the legendary wildlife he had read about in the hunting classics of Africa’s colonial age.

Starting in the early 1960s, Grellmann set about to change that. Little by little, he discovered that the native animals of southwestern Africa did still exist, but in small, isolated pockets. Mainly, he found antelope–kudu, springbok and gemsbok– and convinced the farmers whose land they occupied to not shoot them for five years. In exchange for that restraint, Grellmann, who had started a nascent international outfitting business, promised to bring hunters with money to hunt the conserved animals. The farmers would get paid for every animal taken off their land.

The arrangement worked, but it was slow going until 1972, when a cranky American writer showed up to find a 60-inch kudu for his crack-shot wife. The writer was Outdoor Life’s Jack O’Connor, in the twilight of his illustrious career. By the time he left Grellmann’s company, O’Connor had collected gemsbok, mountain zebra, and his own kudu, most taken with a richly stocked 7×57 that his guides thought wasn’t up to the task.

O’Connor’s Outdoor Life article, “Big Kudu in South West,” opened the gates to American hunters, and Grellmann scrambled to add more ranches to his hunting operation.

Wildlife ranches are now a fixture of Namibia’s landscape, and this model of wildlife conservation has paid off in increased numbers and diversity of wild animals across the country, from the Kalahari to the Caprivi Strip on the Botswana/Angolan border.

Land of the Gemsbok

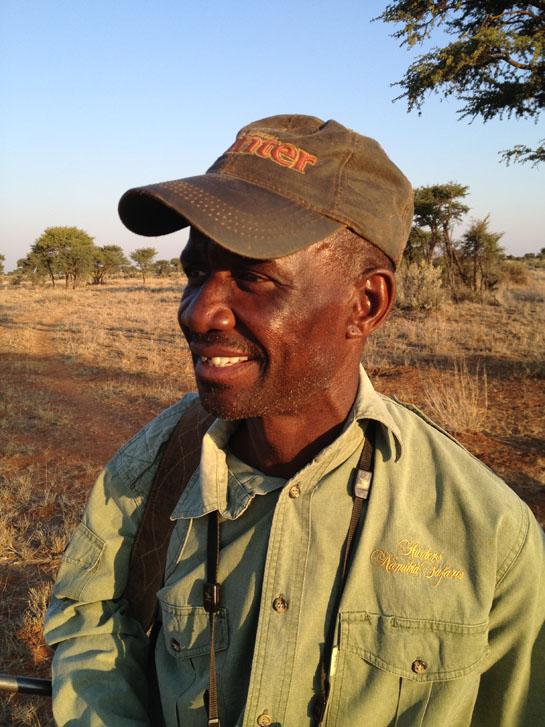

I traveled to Namibia last month to meet Grellmann, and to talk to officials at the country’s Ministry of Tourism and Environment about the future of trophy hunting here. But my real motivation was to hunt big Kalahari gemsbok with Marina and Joof Lamprecht of Hunters Namibia Safaris. Marina may be the most articulate champion of sport hunting on the continent, and she wanted me to hunt with Johnny Hogobeb, a black PH who had trained with Grellmann at one of the nation’s first professional hunter schools.

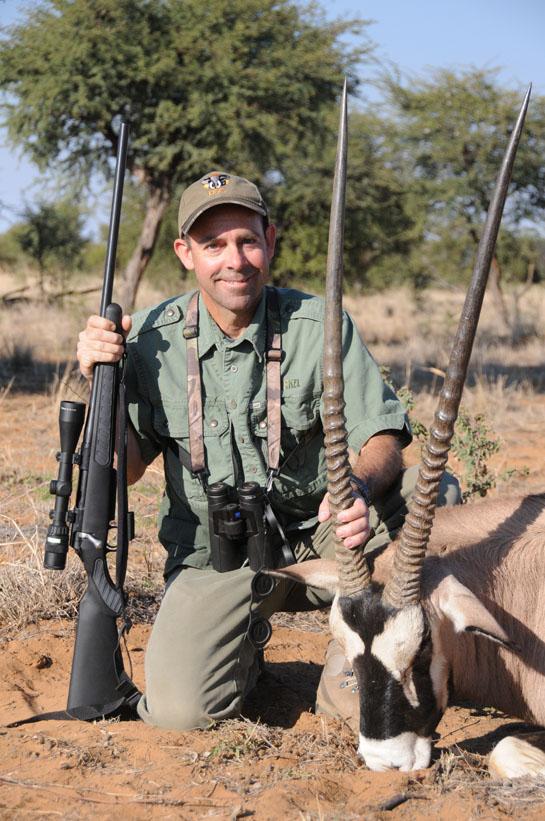

I had previously hunted gemsbok, often called oryx, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape. But the animals clearly didn’t belong in the bushveld. They are open-country antelope, and the first morning hunting them on the Lamprechts’ 80-square-mile property was like seeing them for the first time. We spotted hundred of gemsbok, in herds of a handful to a couple dozen, coursing through scattered stands of camelthorn and leadwood with their black tails swishing and their polished horns flashing in the sun.

I was interested in a bull, knowing that they typically have shorter horns than the cows. But to me, this animal–with its black mask and speared, ringed horns–is the very picture of wild Africa, and to hunt a stout-horned bull would be the pinnacle of my Namibian trip.

What I didn’t appreciate is how hard it is to judge a mature bull, but Hogobeb’s practiced eye found one after another. Each time our stalk would be blown by too many suspicious eyes or because we bumped a wildebeest or an eland that in turn spooked herd after herd of gemsbok. By the end of our first day together I had no oryx, but a very good idea why Joof Lamprecht encouraged Hogobeb, who had been Joof’s go-to tracker for nearly two decades, to enroll in PH courses.

Hogobeb, who came to Hunters Namibia as an apprentice welder and mechanic, quickly developed first-rate field skills. But he also revealed talents that aren’t as definable, but are hugely important for professional hunters–a quick wit, the ability to sense and solve problems with clients and field staff, and an easy-going authority. But like many black Africans, he lacked formal education, which made the written PH exam an insurmountable hurdle. But Marina Lamprecht, working with government ministers and the country’s professional hunters’ association, developed an alternate exam–just as rigorous as the written–that could be taken by illiterate trackers. Hogobeb was one of the first to receive this non-traditional PH certification.

Five Good Bulls

In our second day, Johnny found a herd that included a good bull, and we followed from patch of shade to snarl of brush until I could make a clean shot.

The bull was heavy and tall, a combination I didn’t expect. But what is even more remarkable–and one of the best testimonies I can give about Hunters Namibia’s operation–is that four of us hunters all shot remarkable trophies. Each flirted with that magical 40-inch mark.

I was fully satisfied, but Johnny asked if there was any other animal I was interested in hunting. I couldn’t hide my interest in eland, especially after bumping into numbers of remarkable bulls on the ranch.

Just as the sun was dipping to the horizon, we caught up with an ivory-tipped bull, waited for long minutes until he stepped into the clear, and I sent a Hornady GMX bullet from a .300 Win. Mag. into my first southern eland.

I had an idea this spiral-horned animal–the second-largest antelope after the related Lord Derby eland–was big, but I had no idea how massive mature bulls are until I approached mine. It looked like a brahma bull, with its fleshy dewlap and meter-wide girth.

The whole hunting party, consisting of Johnny, tracker Martin, and hunters Steve Wagner, Ben Carter of the Dallas Safari Club, writer Frank Miniter, and myself were required to pull and tug in unison to get the bull prepped for photos, and then it took all of us, plus the stout winch on the Toyota Land Cruiser, to load the eland into the truck.

I better understand how the eland got its name; it means “moose” in Dutch.

Lunch Duty

One of the lines of inquiry that threaded through my entire visit in Africa was the different ways that wildlife management is being sustained across the southern part of the continent. In some places, that’s being done by recruiting people who wouldn’t traditionally be in the upper echelons of the hunting industry into the business–people like Johnny in Namibia and my black PH, Patches, in South Africa.

Elsewhere, sustainability means encouraging landowners to conserve antelope, as Grellmann argued. In some places, it means helping control crop-marauding elephants or sending in hunters to remove dangerous lions or leopards.

In the Lamprechts’ area, it’s the creation of a program that literally sustains the local community. Nearly all the meat from hunter-killed animals at Hunters Namibia’s operation goes to feed students at a school in the settlement village of Otjibero just down the road.

“We started this as a way to help the local community,” says Marina Lamprecht. “But it also helps us. We had a bit of a problem with poaching early on. So we told the village elders that if we had any more poaching, we would end the meat distribution to their children. The poaching stopped very quickly.”

I had a chance to see first-hand how important the meat–from our gemsbok–is to the students. Long before the simple meal of boiled meat was ready, over 300 students lined up with empty bowls that they had brought from home. There was a mix of lidless Tupperware, wide-mouthed plastic bowls, large coffee cups, and even the hubcap from a car. While they were waiting for the meat to cook in an iron caldron over a wood fire, the students giggled and gossiped and jostled, as though they were waiting for a carnival ride. I talked to the school’s headmistress.

“This meat provides protein that the students are not getting anywhere else,” said Mrs. Hochbro. “But it also provides an incentive for them to come to school. When they have meat, students are more attentive, they learn better, and they are healthier.”

And they don’t poach.

INSIDE THE MINISTRY

My final stop in Namibia was in the capital, Windhoek, to meet with officials from the country’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

I wanted to hear from Namibian ministers themselves about how they viewed trophy hunting. Elsewhere in Africa, governments are aggressively curtailing sport hunting. Most recently, both Botswana and Zambia ended all trophy hunting, and other governments reportedly are on the fence about the economic and environmental benefits of hunting.

But Simeon Negumbo, the permanent secretary of Namibia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism, was blunt:

“Conserving wildlife requires a lot of resources, resources that the government cannot always provide,” says Negumbo. “The resources we get from international hunting are plowed back into the resource, but as importantly for us, into rural communities.”

But how do rural communities benefit, except to be employed in the hospitality industry or as recipients of handed-down protein, as in the case of the Otjibero students?

“Trophy hunting encourages locals to conserve animals, because the more animals that are on the landscape, the more everyone benefits, from wildlife ranchers to subsistence hunters to people who run photo safaris in our national parks,” said Negumbo. Then he added a bit of context.

“During Namibia’s civil war, there was very little trophy hunting,” he said. “There was little control and law, and there was a lot of poaching. We did not have an abundance of wildlife. Now that we are stable, sport hunting is on the rise and we have abundant wildlife. That’s not accidental. Social stability and wildlife abundance go hand in hand. It is cause and effect.”

And in Africa, which has weathered social unrest for much of the last century, that’s an argument that should resonate from Windhoek to Harare to Nairobi.

Check out the Hunting Blog next week for my story on a college course for Professional Hunters.