Dozens of the best spearfishers from around the country dove into Lake Powell to shoot more than 19,000 thousand pounds of fish in two days during the freshwater nationals tournament last month.

The spearfishing teams battled incredibly low water levels due to drought. The reservoir’s last tournament in 2018 saw water levels nearly 90 feet higher. That wasn’t the case this year, and some teams arrived a week early to scout the lake. Even teams who have hunted the lake previously found themselves in unfamiliar territory.

“Scouting was a lot harder because you had basically a different lake. You had to scout as if you’ve never been to the lake before. The structure and everything can change because of the water level,” says Mike Livingston, National Freshwater Spearfishing Association president.

In addition to changing the landscape for hunters to navigate, the record low water levels made for a logistically intense tournament. Only two lanes at one working boat ramp were usable to get more than 20 competing boats in and out of the water in tight time frames.

Teams accustomed to saltwater had to adapt to an entirely new style of hunting. Day one sent teams after gamefish, mostly striped bass and the occasional walleye. Both are non-native species in the lake. On day two, the spearfishers targeted carp. Points were awarded for the heaviest fish, but it was the quantity of fish that could push teams onto the podium.

Instead of deep dives and long breath holds waiting for big fish in the blue water like they might in saltwater, hunters dove repeatedly toward murky bottoms in narrow canyons, reloading their guns dozens of times an hour.

“I think I did 204 or 208 drops on the carp day,” says Justin Lee, who finished first place in the men’s division, bagging 82 fish over 2 days. In his native Hawaii, three-minute breath holds and dives of more than 100 feet into crystal clear water is the strategy.

“You just can’t get the numbers that you need if you’re diving like that. So you kind of gotta change your whole system, your way of diving, to just get more time underwater,” Lee says.

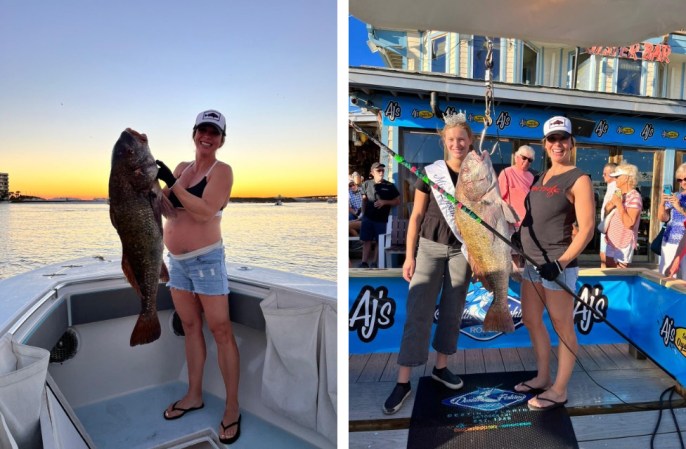

By the end of day two, teams were crammed into boats with hundreds of pounds of carp stuffed into trash bags and barrels. Nicole Burko shot 61 carp and three striped bass. She took second overall in the women’s division.

“It’s a nightmare, you’re dealing with fish slime everywhere. It’s all over the boat, it’s all in your face, and all over your wetsuit,” competitor and 2021 champion Darvil McBride says.

In previous years, the tournament worked with fertilizer producers and reptile farms to donate the massive amounts of carp to useful causes. This year, the National Park Service disposed of the fish from the Wahweap Marina following weigh-in.

Though not officially deemed invasive in Lake Powell by the states of Utah or Arizona, there is a large population of carp that competes for resources with more popular species. In parts of Utah, carp are managed with state removal programs to level the playing field for other fish.

Utah Division of Wildlife Resources biologist Dan Keller started fishing the lake as a teenager and can only recall three times that he has caught a carp on a rod and reel. The efficiency of the spearfishers impressed him, but the impact of the tournament is unclear.

“I would say, Yeah, removing [thousands] of fish from a reservoir as large as Lake Powell probably isn’t making a biological impact,” Keller says. “At the same time, the optimist view is, well, that’s [a few thousand] fish out of there that are competing. Maybe we’re freeing up some resources for some other species.”

Eurasian carp (or common carp) have been rampant in waters across the U.S. since they were brought to the country for cultivation in the late 1800s. The rapidly reproducing species of bottom feeders can crowd out other fish populations and muddy waters as they search for food, eating anything they come across.

The creation of the lake by the damming of the Colorado River in 1963 led to the introduction of other numerous non-native game fish. Species of bass and carp make up the biggest share of the lake’s fish population, competing with native suckers, bonytails, and chubs among others.

Beyond the biological impacts, Keller thinks that the biggest positive is the engagement with the environment that the tournament brings, bringing hunters from all over the country to experience and connect Lake Powell’s fisheries.

The experience changes dramatically year-to-year with Lake Powell’s water level, which has dropped 40 feet since 2021. Keller cites the variable water levels as a tool in the fight against invasive zebra and quagga mussels, which consume phytoplankton young fish rely on. Sites where colonies of mussels settle in are disrupted when dams release water, leaving the mussels high and dry.

As the lake approaches critically low water levels in the second decade of the Southwest’s megadrought, the Department of the Interior is taking unprecedented steps to keep a water level capable of generating hydroelectric power. What’s good for power may also be good for invasive mussels according to Keller.

“If [water levels remain consistent] we might have quagga mussels really build up in high densities and we might see some impacts to the fish populations from that.”

Despite the uncertainty surrounding the state of the reservoir, the National Freshwater Spearfishing Association is on deck to host the world championship in Lake Powell next year, where competitors will fly in from around the globe. Mike Livingston, NFSA president, hopes that a stable, albeit low, water level will lead to a successful tournament next year.

“We truly will have the very best freshwater divers in the entire world convening in one place at a beautiful location to dive and to show how good they are,” Livingston says.

Lee and McBride both qualified to come back next year. Team USA gets four teams for each division: mens, womens, mixed, and masters. Lee is hoping to bring another trophy home to Hawaii.

“Spearfishing, and living outside, off the land is just the way of life. To get some notoriety and to win a national championship, for something that you learned to do as a little boy, or little girl in the small town to bring home food is huge,” Lee said.

Until the competition returns to Lake Powell, Lee says he’ll be training in Honoka’a and “living on cloud nine gazillion.”