There are two common narratives circling President Donald Trump and our country’s public lands. In the first narrative, President Trump’s Department of the Interior is at the bidding of the energy industry, and it’s out to drill, mine, and develop our public lands—and then sell whatever scraps are left to the highest bidder. In the second, President Trump and the DOI are dedicated to supporting sportsmen and women because we boost the economy and fund wildlife conservation. They’ll do whatever they can to increase our ranks, while also promoting responsible resource extraction on public lands.

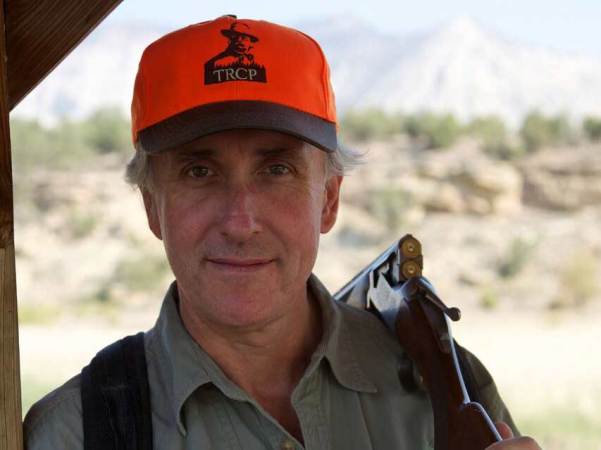

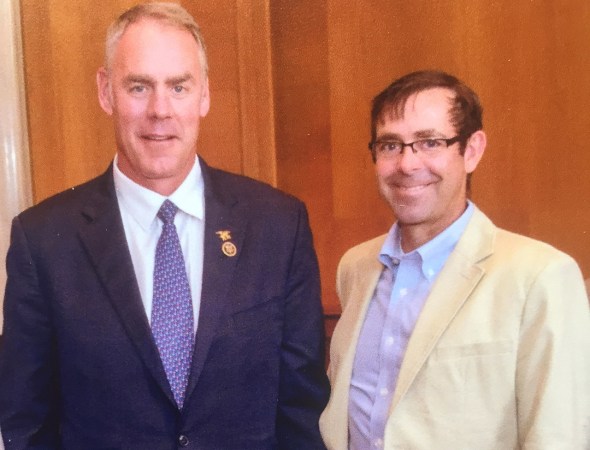

In the middle of both narratives is David Bernhardt, who holds the top spot in Department of the Interior—the federal agency that manages about 500 million acres of public land. Bernhardt was appointed secretary of the DOI in April after serving as deputy to former Secretary Ryan Zinke. While his predecessor was a brash, retired Navy Seal commander who considered himself a “Teddy Roosevelt guy” (remember when Zinke rode a horse through D.C. on his first day of work?), Bernhardt is a lawyer and a former oil-industry lobbyist, who considers himself a careful administrator.

“I am an administrator of an agency that has a whole host of legal obligations that I need to execute faithfully,” Bernhardt told Outdoor Life in a recent interview. “And on top of that, I have the priorities of the President. And that’s because the President’s priorities are the reflection at any one time of the will of the American people. That’s why we have elections, right? Those are my two touchstones. The laws that I have committed to execute … and to the extent that we have policy discretion, to exercise that in line with the President’s priorities.”

So just what exactly are the President’s priorities around our public lands, and how will Bernhardt’s department execute them? Here’s a look at three public-land issues that are critical to sportsmen and women.

Energy Extraction vs. Wildlife Habitat

In May, the President stated: “The golden era of American energy is now underway,” in a press release titled President Donald J. Trump Is Unleashing American Energy Dominance.

That release highlighted a variety of regulatory rollbacks that are designed to facilitate more energy extraction on public lands. Onshore oil and gas revenues from public lands had already hit a record high of $1.1 billion in 2018. According to the DOI, this was achieved by fast-tracking the permitting process on BLM land and reducing drilling times. All of this oil and gas money supports the U.S. Treasury, public education, infrastructure improvements, and state budgets. What’s more, the record revenue numbers were achieved while using the smallest footprint of acreage under lease (25.5 million acres) since the BLM started collecting comparable data in 1985, according to the BLM.

“The law for BLM requires that I have multiple uses. Not make energy dominant or wildlife dominant, but work to balance those uses through planning processes,” Bernhardt says. “That’s my view of how it’s supposed to work.” But some critics contend that the DOI is favoring extraction over wildlife and habitat.

“If you look at how much land the energy companies already have under lease, about half of it is just sitting there,” says Scott Brennan, the Montana State Director for The Wilderness Society. “That land hasn’t been developed, hasn’t been fully scoped. So we’re not seeing the full footprint or potential footprint of that development [yet]…They make the money when they lease it, and then you see the impact later.”

Brennan said many of the rule changes that make energy development easier (like removing protections around sage grouse habitat) are going to have long-term environmental consequences. In January, the department sent a memo that also reduced the public protest period on oil and gas lease proposals.

“There is no reason to cut the public comment period from 60 days to 10 days other than to make it harder for the average guy who has a job and hunts and fishes on the weekends to know about these proposals and to do something about these proposals when they threaten the places where we hunt and fish,” Brennan says. “There’s no other explanation for that.”

The long-term effects of more aggressive energy extraction include more climate change issues, according to The Wilderness Society. The organization released a report in July stating that 4.7 billion tons of greenhouse gases could be released from public lands leased to oil and gas companies under the Trump Administration. “If American public lands were their own country, the fossil fuels extracted on those lands would collectively make it the fifth-largest greenhouse gas emitter in the entire world,” according to TWS. Brennan says climate change issues are already having impacts on access for outdoorsmen and women, and he points to longer forest fire seasons and issues like increasing Hoot Owl restrictions in the West, which prohibit trout fishing on specific rivers in the afternoon because water temperatures are too high (catching trout in warm water makes it more likely to accidentally kill the fish).

“If you can’t go fishing because the water is too warm, that’s an access issue,” Brennan says.

Other major players in the conservation world are more hopeful. Bernhardt could serve as a good ally and representative for sportsmen issues when dealing with the President, says Whit Fosburgh, the president and CEO of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (see our full Q&A with Fosburgh here.)

“I think there is a difference between the people like David Bernhardt and the President in some cases,” Fosburgh says. “For example, you have the President personally intervening to make the Pebble Mine in Alaska move forward, to eliminate restrictions on some logging in the Tongass—things that don’t make sense for sportsmen. I honestly don’t think that the President really understands or cares that much about what sportsmen think. I think that David Bernhardt does. I hope that as Bernhardt stays there, he will be able to speak reason to the President and everybody else that these are important issues.”

Public Access vs. The Sagebrush Rebel, William Perry Pendley

Bernhardt is a lifelong hunter who grew up in Colorado. He says one of his top priorities is strengthening America’s sporting heritage. “In terms of issues that are important to me, expanding hunting and fishing access opportunities, finding good ways to expand participation, recognizing which areas are open…that’s where my passion lies at the department,” he says.

Bernhardt plans to open new hunting and fishing opportunities on 74 national wildlife refuges and 15 national fish hatcheries in time for this fall’s hunting seasons. This is similar to a Zinke initiative that opened new opportunities in 30 wildlife refuges in 2018. Bernhardt says he hopes these new access opportunities will keep more sportsmen and women in the field.

“This President fundamentally understands that sportsmen, without them out there in the field, we face some real challenges on the wildlife side,” Bernhardt says. “If we don’t do things to enhance [hunter and angler] participation, how do you really think we’re going to pay for wildlife conservation going forward?”

Wildlife and public land groups cheered Bernhardt’s refuge plans, then just a few weeks later, those same groups were up in arms over the appointment of William Perry Pendley, a fervent critic of federal public lands, as the acting head of the BLM.

Pendley has penned books about federal overreach in the West, served in the DOI during the Reagan administration where he earned his reputation as the “Sagebrush Rebel,” and once argued in an article for the National Review that “The Founding Fathers intended all lands owned by the federal government to be sold.”

“What we’re most concerned about is the rapid ascension of Mr. Pendley,” says Land Tawney, president and CEO of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. “I don’t know how they think that that is a good idea. It flies in the face of everything that this administration has talked about when it comes to keeping public lands in public hands.”

Even though Pendley, on his own, would not be able to facilitate the mass sale of BLM land, most in the conservation and public lands arena say that it’s foolhardy to put an anti-federal land advocate in charge of 248 million acres of federal public land.

“While it would take an act of Congress to sell public lands in a very robust way, [Pendley getting the] top position sends a chilling effect through the entire organization,” Tawney says. “He can monkey around with budgets, he can monkey around with career personnel, and he can monkey around with priorities.”

For his part, Pendley says he’ll drop his anti-federal-land agenda while heading up the BLM.

“You know, I’m a Marine, and I understand the chain of command and following orders,” he told the Washington Times. “The President has made it very clear that we do not believe in the wholesale transfer of federal lands. That’s the President’s position, that’s the secretary’s position, and now that I’m deputy director of the Bureau of Land Management, that’s my position.”

Just as Pendley is beginning his tenure, BLM is moving its headquarters from Washington D.C. to Grand Junction, Colorado. Some critics argue that the move is a tactic meant to clean house on BLM senior leadership (who won’t want to move) and systematically dismantle the agency. Of the approximately 10,000 BLM employees, only about 500 work out of the headquarters in D.C. Eighty-five federal jobs will move to Colorado, according to the Denver Post.

Lawmakers from both sides of the aisle, along with Bernhardt and Pendley, think the move west will better connect the bureau with the land (the majority of BLM land is located west of the Mississippi) and people it manages.

“Our frustration in the West is simply we’re dealing with a landlord who’s 2,000 miles away,” Pendley told the Washington Times. “You just don’t understand situations without being on the ground. You just have such a better perspective. You can read all you want. You can listen to all the PowerPoints you want. You can have as many conference calls as you can plug into a day, but you don’t understand until you’ve got boots on the ground.”

Read next: A Conversation With TRCP President and CEO, Whit Fosburgh

Land & Water Conservation Fund vs. The Maintenance Backlog

Only a few members of Congress oppose the popular and effective Land and Water Conservation Fund, which takes money from offshore drilling royalties to fund federal and state public-land projects. LWCF funds have been used in all 50 states to create parks, boat launches, hunting areas, and more. The best part: This costs taxpayers $0. Even though it had unanimous support in the hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation world, Congress allowed the fund to expire a year ago.

The LWCF got new life when it was permanently reauthorized in the massive public lands bill, which Bernhardt supported and the President signed in March. But here’s the catch: Even though the LWCF was reauthorized, no funding was dedicated to it.

It’s up to Congress decide how much money the LWCF should get. The max Congress can allocate is $900 million per year, but that’s only happened twice since the LWCF was started in 1964. In its most recent budget, the DOI requested essentially no funding for new land acquisitions through LWCF.

“I believe the LWCF is a very important program, but it’s not the only thing for land management,” Bernhardt says. Both he and former Secretary Zinke promoted a plan to fix the massive maintenance backlogs in National Parks and BLM land before acquiring new land through LWCF.

“We promoted a slightly different idea, which was, Hey, we have a big infrastructure problem on the lands that we currently manage,” Bernhard says. “We have a tremendous backlog in the Park Service, but also in the Refuge system and also in BLM. So we came up with a similar model, which is we take new revenue from all forms of energy and we use it to create a dedicated fund. The difference being that our dedicated fund was a mandatory spending obligation. So what that would do, is Congress wouldn’t appropriate it on a yearly basis, it would just be a fund that we could utilize.”

The maintenance backlog for national parks is currently around $11.6 billion.

“We have not taken care of investing in things,” Bernhardt says. “It’d be like if you just decided to live in your house and not paint the trim or fix your windows or fix your roof for 30 years. That’s where we are as a society. The parks maintenance fees when you look at it, half of it is roads.”

Experts from the public lands community agree that fixing the backlog on national parks is critical, but Fosburgh of the TRCP says that shouldn’t come at the expense of the LWCF.

“It’s not an either-or situation,” he says. “…The backlog is a fault of Congress systematically starving the agencies for decades now, then claiming, ‘Golly, we can’t fund the LWCF because we have this maintenance backlog.’ Which is completely disingenuous, and I think that most people see right through that sort of argument.”

A bright spot for hunters is that Bernhardt wants to focus money on public access if Congress does go through with funding the LWCF. Given the amount of landlocked public land, that strategy could be a huge win for outdoorsmen and women.

“The one thing I think we’d want to do, no matter how much money we receive from LWCF, is that we target lands that give us the best bang for our buck,” Bernhardt says. “I ask that we use it to maximize public access. If we can acquire a little strip of land that opens up thousands of acres, I view that as a pretty good deal.”

As for the next budget request, Bernhardt is optimistic—cautiously optimistic—that the President will call for more LWCF funding.

“You go through a process within the administration and that’s the priority,” he says. “I’m optimistic that I’ll have the ability to have a slightly different budget for LWCF now that it’s authorized, but that’s a work in progress.”

—Matthew Every contributed reporting to this story.