We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Although Winchester Arms has a history of innovations and consumer loyalty perhaps unmatched by any other gunmaker, its experience with autoloading shotguns has not always been rosy. The sad tale begins in 1899, when John Browning brought Winchester a plan for a self-loading shotgun. Until then the two had enjoyed a mutually beneficial working agreement, with Browning’s patents being used in some of Winchester’s most successful guns.

Incorporated into some of Winchester’s most successful guns. This time, however, rather than selling his rights to the new gun, Browning wanted a royalty arrangement, which Winchester refused. So Browning took his design and patents to Remington, which introduced the shotgun in 1905 as its Model 11-the gun that was to earn smoothbore immortality as the Belgian-made square or “humpback” autoloader bearing Browning’s name.This time, however, rather than selling his rights to the new gun, Browning asked for a royalty arrangement, which Winchester refused. So Browning took his design and patents to Remington, which introduced the shotgun in 1905 as its Model 11-the gun that was to earn smoothbore immortality as the Belgian-made square or “humpback” autoloader bearing Browning’s name.

One of the ironies of Browning’s falling-out with Winchester is that it was a Winchester engineer who helped Browning write the patent applications for his autoloader. Moreover, the patents proved so ironclad that Winchester’s efforts to produce an autoloader of its own design were seriously crippled-a fact glaringly and somewhat shamefully obvious when Winchester introduced its own autoloader, which in the company’s fashion was named for its year of introduction, 1911. Winchester sidestepped the Browning patent for an operating handle on the bolt-the M1911 didn’t have one! Instead, the mechanism was cycled for loading and unloading by grasping the barrel and jacking the whole works up and down. This feat was made somewhat easier by a knurled gripping surface on the barrel near the muzzle, but it wasn’t all that pretty, and the poor M1911 didn’t become much of a favorite.

[pagebreak] Early Guns

Winchester had another go at making a self-feeding shotgun with its M40 (yep, 1940), which came to be called the “Gooseneck” model because of its rounded receiver profile. Apparently, Winchester’s engineers had something else on their minds when they designed the M40, but the gun never got much chance to prove how bad it was because WWII came along and production ended, never to be started again. Only about 12,000 of the guns were made, which excites collectors of rare Winchesters.

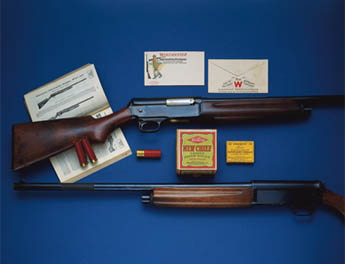

Winchester’s autoloading shotgun fortunes improved considerably with the M50. (Nope, wrong guess. It was 1954, but they already had an M54 rifle.) In my not unbiased opinion, the M50 is the most gracefully contoured, cleanly detailed, smoothest-working autoloading shotgun ever made, before or since. Winchester escaped the Browning curse with the M50 because on its engineering staff was no less a wizard than Marsh “Carbine” Williams. Like Williams’s carbine of WWII fame, the M50 operated on the short-recoil principle, with the “floating” chamber recoiling about a tenth of an inch within the fixed barrel. This eliminated the “double-shuffle” effect of Browning’s long-recoil system, in which the recoil-driven bolt moves rearward with the barrel. As slick as the M50 (which came in 12- and 20-gauge) was, however, a butt-heavy feel caused by a weighty inertia rod in the butt section brought it ongoing criticism.

The M50 might be called the last shotgun of the “old” Winchester-meaning the metal was nicely machined, fitted and finished, with honest hand checkering on the wood. But pretty as it was, the M50 did not become the autoloading equivalent of Winchester’s great M12 pump gun. The 1950s saw rapid changes in gunmaking and design. Postwar Europe was becoming a factor and Remington s a dominant force in the shotgun market. What Winchester needed was a blockbuster attention getter, an autoloader that wasn’t just new, but also different.

A Glass-Barreled Wonder

That something different was the M59 (yep, born in 1959). Actually, the mechanism and operation of the M59 was identical to that of the M50, with several interchangeable parts. But what was radically different about the M59 was that it had a glass barrel! Not glass like a beer mug, but some 500 miles of thin glass fibers wrapped around a steel tube. To what advantage? Win-chester claimed that the glass barrel was stronger than ordinary steel barrels, and proved it by plugging the bore with a 20-gauge shell and firing a 12-gauge load behind it. The glass barrel survived the test.

Winchester got a lot of good press for the M59, but not enough to counter the buying public’s negative response to the bulky look of the glass-wrapped barrel. Winchester also offered the M59 with a curious feature called a Versalite choke, which screwed into the muzzle and offered different options of shot patterns with a single barrel.

Critics maintained that “screw-in” chokes were unworkable gadgets that would never succeed. A few M59s were made in 20-gauge and even an experimental 14-gauge. (If you run across one of these, try to buy it.) But after about five years of scant success with the M59, Winchester threw in the towel and went back to its by now well-used drawing board. John Browning was probably giggling in his grave.

[pagebreak] The ’64 Change

For Winchester aficionados, and indeed for the gun industry as a whole, time is measured before and after 1964. That’s the year a new line of shotguns and rifles was introduced, signaling Winchester’s departure from traditional ways of making guns in favor of more cost-effective manufacturing.

That year, 1964, the gas-operated M1400 sold for $134.95, and the highly successful Remington M1100 gas gun was priced at $149.95, which gives you some idea of what the bosses at Winchester had in mind, and how badly they wanted into the autoloading shotgun market.

With its gas-operated, rotating lug-locking system, the M1400 was backed by solid engineering; aesthetically, however, it was as charming as Cinderella’s stepsisters. Nevertheless, compared with Winchester’s previous attempts at self-feeding shotguns, the M1400 was a smashing success. By the time it was discontinued in the 1990s, it had had a longer life span than any other Winchester autoloader and had sold more than three times as many as all previous models put together!

Even so, some of the old-timers at Winchester were smarting from the jabs at their post-1964 products and vowed to show the shooting world they could still make guns the old-fashioned way if they wanted to, which they set out to do with a clean sheet of paper on their drawing board. So late in 1973, my second year at Outdoor Life, I got a call from a big shot at Winchester inviting me to join him and a few other writers at a shooting club on Long Island to partake in the unveiling of a brand new shotgun made the way they used to make ’em. It was the Super-X Model 1.

As the company promised, its newest autoloader looked a lot like “old” Winchester, with machined steel and nicely finished wood with cut (not impressed) checkering. There was even some reminiscence of the immortal M12 pump gun, which Winchester confessed was intended, so as to recapture the flavor of classic Winchester. The new shotgun also benefited from some solid engineering, particularly in its gas-powered operation. Unlike many existing gas-operated systems, which can be likened to a pump gun with a gas-powered piston driving the mechanism, the Super-X had an unconnected gas “piston” that traveled only far enough to set the bolt into motion, after which the remaining sequences of the opening-ejection cycle were energized by momentum. Further, rather than the bolt locking into the receiver (àla the M12), the Super-X’s two-section bolt locked directly into the barrel-an elegant piece of engineering. What wasn’t to like about the Super-X was its 8½-pound heft, which the Winchester people tried to avoid discussing but was generally considered the price you had to pay for the gun’s all-steel construction. The gathered writers were as one in recommending that a squiggly rolled-on decoration on the receiver cheapened the gun’s appearance and should be eliminated. Winchester failed to do this, but another of our recommendations that was incorporated into the gun (a hand-rubbed finish instead of its original glossy finish) turned out to be a disaster and was later abandoned.

The Super-X was also a bit pricey, with the field-grade selling for $330 in 1975, whereas Remington’s M1100, which dominated the autoloading market, was priced at $245. In short, the Super-X was too heavy and too expensive to be a winner, so in 1981 Winchester gave up and stopped production except for limited custom-shop grades. The Super-X Model 1 was a noble effort; if you can find one at a fair price, buy it, because they are certain to escalate in value.

[pagebreak] Today’s Super-X2

Winchester’s current autoloading smoothbore, the Super-X2, takes a bit of explaining. First catalogued in 1999, this latest model obviously borrows its name from the previous model, and like that earlier autoloader, it operates on a gas-driven, short-impulse system. Spotting any other family similarities requires considerable imagination, to the point that we can even ask in all fairness whether it is a Winchester.

It’s no secret that Winchester and Browning Arms now are very much intertwined. The relationship between the two would be too complex to explain here, even if I understood it, but stamped on the barrel of a Light Field Super-X2 I tested recently are words that tell much of the story: “Mfg by FN-Belgium.” The irony here is exquisite because FN-Fabrique Nationale-is best known to American hunters as the maker of John Browning’s square-back autoloader, the very same gun rejected by Winchester over a century ago. (I bet old John would get a hoot out of this.)

If you compare the Super-X2 with Browning’s Gold autoloader, you’ll quickly recognize that they are identical in several ways, with some parts being interchangeable, but you’ll also note that the Browning is better finished and detailed than the Winchester. This may make you wonder why such a legend-ary American brand as Winchester is being treated like a second fiddle. Ask a citizen of Liège, Belgium, about this and he’ll give you a pretty good answer.

Liège is a historic center of European gun making, and back in 1897, following disastrous wars and a severe economic depression, the le were energized by momentum. Further, rather than the bolt locking into the receiver (àla the M12), the Super-X’s two-section bolt locked directly into the barrel-an elegant piece of engineering. What wasn’t to like about the Super-X was its 8½-pound heft, which the Winchester people tried to avoid discussing but was generally considered the price you had to pay for the gun’s all-steel construction. The gathered writers were as one in recommending that a squiggly rolled-on decoration on the receiver cheapened the gun’s appearance and should be eliminated. Winchester failed to do this, but another of our recommendations that was incorporated into the gun (a hand-rubbed finish instead of its original glossy finish) turned out to be a disaster and was later abandoned.

The Super-X was also a bit pricey, with the field-grade selling for $330 in 1975, whereas Remington’s M1100, which dominated the autoloading market, was priced at $245. In short, the Super-X was too heavy and too expensive to be a winner, so in 1981 Winchester gave up and stopped production except for limited custom-shop grades. The Super-X Model 1 was a noble effort; if you can find one at a fair price, buy it, because they are certain to escalate in value.

[pagebreak] Today’s Super-X2

Winchester’s current autoloading smoothbore, the Super-X2, takes a bit of explaining. First catalogued in 1999, this latest model obviously borrows its name from the previous model, and like that earlier autoloader, it operates on a gas-driven, short-impulse system. Spotting any other family similarities requires considerable imagination, to the point that we can even ask in all fairness whether it is a Winchester.

It’s no secret that Winchester and Browning Arms now are very much intertwined. The relationship between the two would be too complex to explain here, even if I understood it, but stamped on the barrel of a Light Field Super-X2 I tested recently are words that tell much of the story: “Mfg by FN-Belgium.” The irony here is exquisite because FN-Fabrique Nationale-is best known to American hunters as the maker of John Browning’s square-back autoloader, the very same gun rejected by Winchester over a century ago. (I bet old John would get a hoot out of this.)

If you compare the Super-X2 with Browning’s Gold autoloader, you’ll quickly recognize that they are identical in several ways, with some parts being interchangeable, but you’ll also note that the Browning is better finished and detailed than the Winchester. This may make you wonder why such a legend-ary American brand as Winchester is being treated like a second fiddle. Ask a citizen of Liège, Belgium, about this and he’ll give you a pretty good answer.

Liège is a historic center of European gun making, and back in 1897, following disastrous wars and a severe economic depression, the