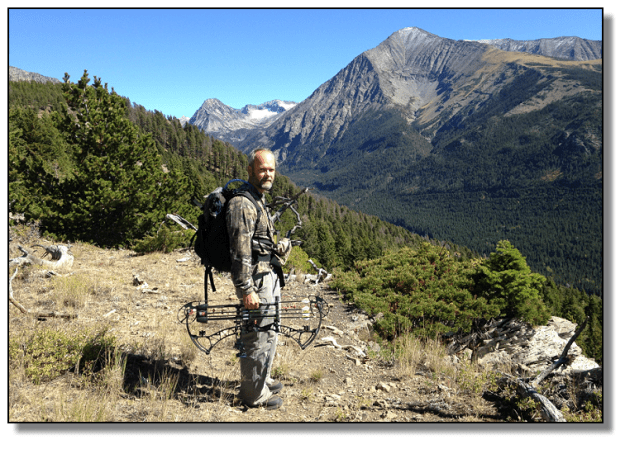

You greet 5 a.m. with your boots on, headed uphill. By dawn, you are miles from camp and have a band of 12 elk in your binocular. They’re grazing lazily away from you along the opposite slope, flirting within rifle range in the early morning quiet. And like you, they are standing on public land.

There are no fences or physical obstacles separating you from the herd, and you could walk to them without ever setting foot on private property. Moving into shooting position, however, could earn you a trespass charge.

Because standing in your way is an invisible, dimensionless barrier—the point at which two parcels of private land and two parcels of public land meet corner to corner, like the black and white squares of a chessboard. You’re pinched by a corner crossing, and out of luck. The elk are as safe as if they were standing on inaccessible private land.

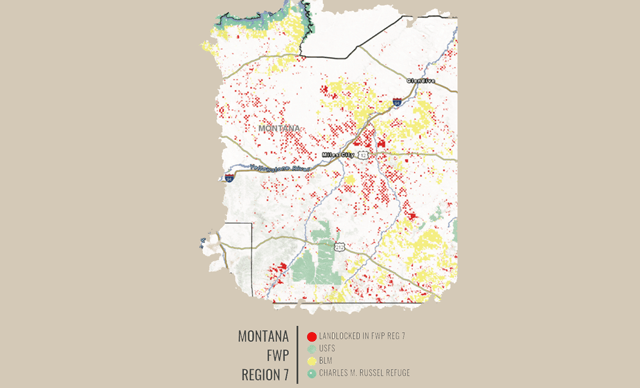

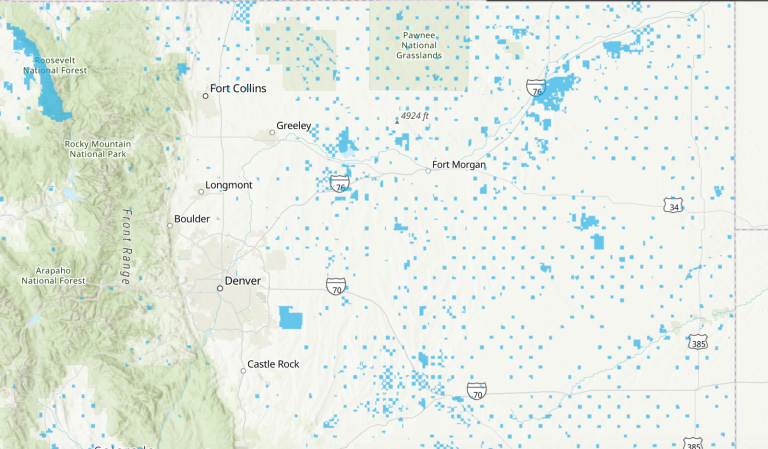

If the situation sounds painfully familiar, you’re not alone. According to Landlocked, a GIS-based public access mapping study conducted by the Center for Western Priorities in 2013, more than 1.5 million acres of public land in the intermountain West are effectively off limits, thanks solely to the public’s inability to legally step across corners.

The corners are remnants of centuries-old land-management policies, by which the American West was divided into a giant grid of square, 640-acre “sections.” It was a handy system for making sense, at least on paper, of a sprawling, unknown wilderness. The grid survey also served well for distributing land to territories to form states; to homesteaders to encourage settlement; to corporations to build railroads; to Native American tribes for reservations; to the military to build bases; and for otherwise disposing of the young nation’s vast real estate holdings.

What wasn’t sold or transferred remained federal land, and is today managed for the beneficial use of all Americans by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Forest Service, and National Park Service. This is the land on which most western sportsmen hunt and fish.

Parcels have, over time, been divided, combined, and reshaped by the hands of commerce and politics. Not everything is perfectly square anymore. But the original grid can still be imagined as a multi-colored Tetris puzzle—a square of BLM land, nestled inside an L-shaped state parcel, which abuts a T of private ground, and a long skinny rectangle of National Forest—that are western property maps today. There are still plenty of corners.

LOCAL ENFORCEMENT

The corning crossing conundrum was, in contrast, born largely by a lack of explicit policy. There has never been a federal statute, no law enacted by the democratically elected representatives of the American people, that defines what property rights are, and are not, afforded at the corners. Who has use of, and who can pass, chess-bishop fashion, the imaginary point where four parcels meet? We’ve never decided for ourselves at a national level. Instead, the question has been left for regulators, judges, and enforcement agencies to answer, on a state-by-state, or even county-by-county, basis.

For lack of clearer guidance, most jurisdictions have, according to University of Colorado Law School Professor Mark Squillace, based their positions on the 1979 Supreme Court case, Leo Sheep Company vs. United States. In it, the U.S. government was denied a road easement across Leo Sheep Company land; an easement that it claimed was necessary for access to the federally managed Seminoe Reservoir in central Wyoming. It’s a stretch, of course, to equate road construction with a hunter stepping over a corner. But the case set a precedent for the supremacy of private property rights in matters of public-land access. That’s been good enough to lock hunters out of otherwise legally accessible land in most of the intermountain West.

The de facto ban on stepping from public land, to public land, over an intersection with private, hits sportsmen and –women hardest in Montana and Wyoming. There, access to 724,000 and 404,000 acres respectively is lost behind such corners.

It’s not surprising, then, that citizens of those states should try to finally define the law for themselves, via the democratic process.

House Bill 171, introduced to the Wyoming Legislature in 2011, was an attempt to do just that. It would have decriminalized corner crossing, had it not been roped and euthanized in the House Agriculture Committee.

In 2013 hunters, anglers, and other outdoor enthusiasts rallied behind a similar attempt in Montana. H.B. 235 enjoyed vocal popular support, but it too died an ignominious death.

Large landowners, it turns out, still hold immense political sway in the Rocky Mountain states.

That may explain why hunters in Utah, Idaho, New Mexico, and Colorado have more or less resigned themselves to the status quo. Corner crossing in these states remains a prosecutable offense, but with far fewer affected acres than Wyoming and Montana, the issue is less pressing.

Sportsmen on the ground describe enforcement regimes that vary from district to district. In Washington, enforcement takes a common-sense perspective. According to Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Region 1 Enforcement Coordinator Capt. Dan Rahn, “If someone knows where they’re at, and they’re correct, and they step from public to public without setting foot on private land, they’re not trespassing. No Washington officer that I know would cite someone for that.”

Hunters in many of these regions have decided, for better or worse, that a “don’t ask, don’t tell” style “truce” is preferable to the likely result of a legislative battle. Even if that means an occasional early morning spent watching the herd wander unpursued over the horizon.