There’s more to wild birds than the legs and breasts. Hidden beneath the breast bone is a holy trinity of organs that can be turned into fried goodness. I’m talking about wild bird giblets: the heart, liver, and gizzard.

The concept of saving wild giblets is another way to use as much of the bird as possible. But I’m not going to get preachy with an argument that starts with “the bird gave its life so…” Instead, I’ll say those giblets are at least another couple ounces of meat (upwards of half-pound on a big spring tom) that can be turned into some of the most delicious wild game meals you’ve ever eaten.

Now think if you’re processing a limit of roosters in Kansas, that’s 8 ounces of extra meat—one sizable burger’s worth. Or another way to think about it: A limit of giblets is one tray of fried appetizers. But before we start talking cooking techniques, let’s discuss how to pull and clean giblets.

What are Giblets?

For this article, I’m referring to the gizzard, heart, and liver of wild birds. Yes, in terms of offal you can save more, but I consider these three parts the most valuable table fare. Both the gizzard and the heart are just another form of muscle—with different textures than the breasts and legs—while the liver is meat of a different flavor. All are edible and all have their place in a hunter’s culinary repertoire.

Cleaning a Bird to Save the Giblets

Regardless of whether you are plucking or skinning your birds, if you cut below the keel bone with a small incision, right below where the breasts end, you can insert a couple fingers and open up the bird wide enough to pull out the innards. Another method, if you plan to spatchcock your birds (cut out the spine and flatten bird), you can remove the spine and pull out giblets from the back. I toss all the guts and save the heart, gizzard, and liver. While you can reach up and pull out the heart by hand, sometimes you may need a knife to sever the gizzard and liver from the guts.

How to Find and Clean the Gizzard

To help them digest their food, birds eat grit which is stored in their gizzard. This organ is located in the middle of the bird’s body cavity and is the largest, most solid organ inside the bird. Grab hold and pull, snip off any intestine attached so you’re working with just the gizzard.

To clean the gizzard:

- Take a knife and cut horizontally near the intestine hole and open, revealing the grinder plate.

- Use a large bowl with warm water to rinse out the grinder plate of all grit. Do not put this water and grit down your drain, but rather empty outside in yard.

- Freeze the gizzard for 30-60 minutes to facilitate cutting off grinder plate and silver skin. A slightly frozen gizzard is easier to trim. Some folks keep silver skin on, but I don’t because it has an adverse affect on flavor.

- I cut the gizzard in half, but you don’t have to. I’ve found it’s easier to clean if I am working with two halves.

- I first trim off silver skin on both sides, using the grip of the grinder plate on the bottom to help keep gizzard steady while I trim.

- Lastly, I cut off the grinder plate. All I want is ruby-red meat in the end.

How to Find and Prepare the Heart

The heart is located in the upper portion of bird’s body cavity. Reach up and you’ll feel a tight ball of muscle. Pull it out. You’ll recognize it immediately. Use a knife or fingernails to clip any attached arteries. For bird hearts, I don’t clean them the way I would a deer heart—meaning I leave the fat on and don’t cut it open. I leave wild bird hearts whole, rinse them off, and squeeze out any blood in the process.

How to Find and Prepare the Liver

The wild bird liver is likely the most discarded giblet. This nearly gelatinous bit of meat varies significantly in texture compared to the gizzard or heart. It looks almost too flimsy for culinary purposes. But don’t be fooled.

Compared to a venison liver, a bird’s liver is larger in relation to its body. I’d also argue wild bird livers require less effort to make them edible, compared to big-game livers.

To remove and clean a liver, carefully pull it from the guts (it’s that large, dark-purple oval). Snip the vein attaching it to that pile. Make sure that vein is removed—you don’t want to cook or eat it. Rinse under cold water.

How to Cook Wild Bird Gizzards

You can add the gizzard to your grind for either spaghetti or even burger. A grind that consists of 75 percent breast meat and 25 percent gizzard is quite tasty and creates more innate, wild-game flavor tones. With waterfowl giblets and waterfowl meat turned into grind, you can of course cook medium rare if you like.

However, likely the classic method is fried gizzards. For this, I prefer to soak my gizzards (after cleaning) in buttermilk for 48 hours then throw through 1:4 ratio of spice mix to flour and fry at 375 degrees until golden brown. Recently I used The Provider Fowl rub for a batch of mallard gizzards, and they turned out perfectly.

How to Cook Wild Bird Hearts

Cooking a bird heart can be really simple: Sear quickly in bacon grease or duck butter with a little bit of freshly cracked black pepper. Generally speaking, similar to venison heart, wild bird hearts are best served medium-rare, but can be enjoyed in a few different ways. You can fry them alongside gizzards, or you can add them to your grind.

How to Cook Wild Bird Liver

Liver has a more distinct taste. That’s probably why pâté is one of the most popular use for livers. I’d consider making a good pâté to be about the same level of challenge as making a quality sausage. So for this recipe, I had to recruit a friend.

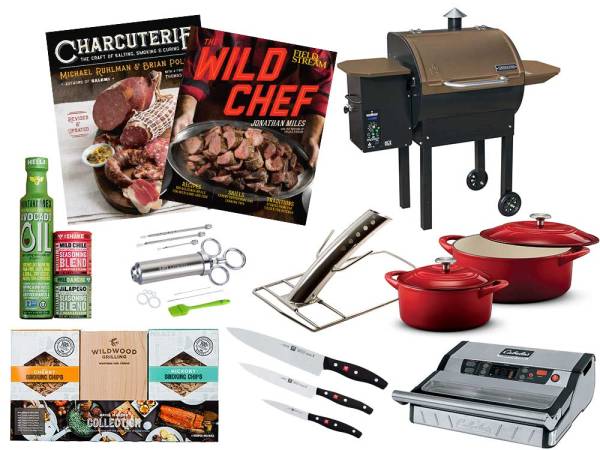

Cosmo Goss is a Culinary Hospitality Consultant with Graduate Hotels in Nashville, New York, and Seattle, as well as the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood. He spends a large chunk of his time working as the chef and culinary director at the Shalhoob Meat Company in Santa Barbara. Goss has made thousands upon thousands of pounds of pâté and has won awards for his charcuterie spreads. His main advice for making an amazing pâté: “Quality of ingredients is most important thing to remember. Ninety percent of pâté recipes call for cognac or whiskey. Buy the good stuff, not stuff cheap stuff in plastic bottles.”

The recipe for Goss’s own wild liver pâté is delicious and will win over anyone who spreads it over a toasted baguette.

Wild Liver Pâté

You definitely want a blender for the recipe. A food processor won’t get the smooth consistency that’s synonymous with pâté.

Ingredients:

- 1 pound wild bird livers (veins and excess fat removed)

- 1/2 white onion, cut julienne

- 3 cloves garlic, chopped

- 1/2 cup unsalted butter

- 2/3 cup rice vinegar

- 3 tablespoons cup fish sauce

- 6 tablespoons mirin rice sweet cooking wine

- 1 tablespoons Sambal chili paste

- 1/3 cup heavy cream

- 1/4 teaspoon curing salt #1

- 1-1/2 teaspoon kosher salt

- Rice bran oil or other high heat oil

Add about 3 tablespoons rice bran (or other high-heat) oil to a large sauté pan over high heat. Pat the livers dry and when the oil is just to the smoking point (approximately 450 degrees Fahrenheit), carefully add them to the pan in a single layer. Do not crowd the pan, as you want a solid sear. Sear for 1-2 minutes until golden brown and flip cook for another minute and remove the livers from the pan and set aside.

Add the onion slices to the pan and reduce heat to medium. Lightly salt and pepper. Stir onions until seared and slightly caramelized (approximately 15-20 minutes) then add chopped garlic and butter. Cook for another 3-5 minutes, stirring frequently. Add the vinegar, fish sauce, Mirin and Sambal chili paste and bring to a simmer. Let it simmer until the liquid has reduced by 2/3-3/4 (so, ideally, only 1/4 of original amount of liquids remains).

Add the livers back to the pan and cook until the livers are just warm. Remove pan from heat. While the liver mixture is still warm, place mixture into a blender with all the remaining ingredients except the heavy cream. Blend on high until the mixture is smooth, about 1-2 minutes. Reduce the speed to medium and slowly add the cream.

Taste the mixture. It should be just salty, but if not, season with a little more salt. Transfer the pâté to a non-reactive container (glass, for example) and cover with plastic wrap, placing the wrap directly on the pate itself so it prevents oxidation. Place in an ice bath covering the mixture by three-quarters. Once cool place in the fridge. This will stay good in the fridge for up to 10 days. Serve on toasted bread with some quality pickle slices. Enjoy!

Can You Eat Giblets from Aged Birds?

Short answer: Yes, you can. Slightly less-short answer: If the giblets smell “off” after cleaning, trust your nose and like with any meat: “When in doubt, throw it out.”

Can Your Freeze Wild Bird Giblets?

Absolutely, just make sure to clean them first. I once froze a spring tom’s gizzard without cleaning. Upon removing months later, when opening up, it was one of the gnarliest things I’d ever seen—like something from one of the Alien franchise movies. So make sure to clean. Otherwise, giblets freeze and keep, generally speaking, the same as any other cut of wild meat.

Any questions or comments, reach out to the author on Instagram @WildGameJack.