We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

The 40-yard mark is where most shotgun enthusiasts see their shooting take a nosedive. There are a few reasons why this happens. The first is simple: The farther a target is from your shooting position, the harder it is to hit. You also need to use different shotgun swing techniques to connect with clay birds. Also, shot patterns—no matter what choke or shot size you’re using—are going to be worse at 40 yards and beyond than they are at 21 yards, which is the distance to the center crossing point in American skeet.

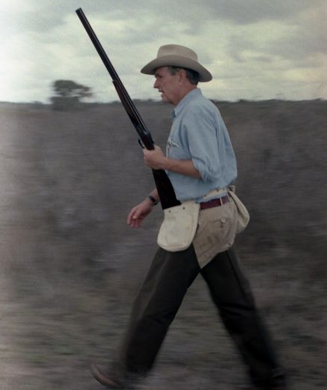

With the help of Field & Stream Shotguns Editor Phil Bourjaily, I’m trying to learn how to become a better shooter beyond 40. I’m not doing it so I can kill game birds at 40-plus yards. I don’t advocate longer shots on wild birds because it increases the chance of cripples. But understanding where to shoot and what technique to use in order to break clay targets at longer yardages can make you better at skeet, trap, sporting clays, and hunting birds. It’s a similar concept rifle shooters use when they shoot out to 1,000 yards: It turns a 200-yard shot into a no-brainer. That’s what I am after, only with a shotgun.

Here are the basic mistakes to avoid—and a few tips—to become a better shotgun shooter past 40 yards.

1. You’re Too Good of a Shot on Live Birds

Killing pheasants over a good bird dog or shooting ducks in the decoys is fun. But it doesn’t prove you’re a good shot, even if you rarely miss. I love both these hunting pursuits, but you don’t have to take much lead into account when a rooster flushes or a pintail is backpedaling over the spread. Some hunters have trouble making the transition from shooting accurately at wild birds to shooting clay birds, because the latter often requires you to get your barrel farther in front of the target and keep it there for a longer amount of time. This may only be a second or two, but it’s plenty of time to make a mistake. Unless you shoot woodcock or mourning doves, clay birds are also a smaller target to hit and they move faster than most wild birds.

Understanding that the approach is much different between shooting wild birds at 25 yards and shooting clays at over 40 yards can be tough for many hunters to comprehend (it certainly was, and remains, a challenge for me). Most hunters who can shoot birds well will look at the front of a duck or rooster, pull the trigger, and kill it. In the grouse woods or in quail hunting, many hunters will snap shoot these small birds, covering them with the barrel and pulling the trigger. Neither of these two techniques works well when shooting over 40 yards, which I’ll get into later. Your approach to hunting isn’t the same as it is shooting clays. Once you reconcile yourself to that, this process becomes far less frustrating.

The best example I can give you: Bourjaily and I hunted the Iowa pheasant opener, and I killed three roosters with three shotshells. That afternoon, we shot five stand and there was one looping target that I never broke in 25 shots. I kept trying to shoot it like it was a wild bird, and paid an embarrassing price. I let the way I shoot when I hunt get in the way of shooting like I needed to in order to break that clay. There’s a difference, and recognizing that is half the battle.

2. Your Mount and Lead Need to Be Better

Every little thing matters when you start shooting targets over 40 yards, starting with your mount. When you shoot low gun—mount, start your swing, then shoot—you’re going to have a difficult time connecting at long range. It all needs to be one compact motion. You need to look in front of the the shooting house or clay bird trap so you can see the bird when you call for it. Don’t look directly at the house or trap; that will put you behind the bird when it’s thrown. Your barrel must be even farther in front of where you are looking so you can see the bird and start moving the gun. Match the speed of the bird (your brain will take this over with practice) with your barrel, then bring the gun to your cheek for a full mount, see the clay target, and fire. If you want more information on this shooting method, check out Gil and Vicki Ash’s OSP School and teachings.

I practiced this mount on skeet first with Bourjaily before moving on to longer targets. Starting at shorter ranges is a good way to begin if you don’t already shoot this way, because it takes some getting used to and close-range shots are easier. It completely changes the way you shoot, and you will likely struggle with it. But in the long run it’s the best method for improving your shooting skills.

Also, make sure that when your cheek is on the stock you can see as little of the gun as possible. You should only be able to see the rib of the barrel. If you can see more of the gun, it probably means your head is too high, which will lead you to shoot high. That’s going to make your shot placement more difficult at longer yardages because visually you need to aim under the target and see more of the clay bird. If your mount is bad, you will be shooting over the top of the bird.

You can get away with a poor mount on skeet or trap at shorter yardages—I have for many years—and still shoot well. But this won’t last as you try to stretch out your shots. The margin for error shrinks at greater distances, and you have to be much more precise with your shot placement.

3. Master Continuous Lead

Top sporting clays competitors are among the world’s best shotgunners. This is because they have to shoot a variety of targets at varying distances, which requires different techniques. For example: Like many hunters, I am a pull-through shooter. I start behind the target, move my barrel past it, and shoot. It’s a very effective way to shoot birds at close range, but it doesn’t work as well on targets beyond 40 yards. Your timing has to be incredibly precise if you pull through targets past 40 because the shot window shrinks the farther away the clay is from you.

To shoot long distance, you must learn continuous lead. For continuous lead, you will keep the shotgun barrel out in front of the clay bird the entire time, and pull the trigger when you want to break the target. The lead distance will vary the longer the shot is. Continuous lead is easier if the bird is flying on a straight line. But if it’s not, that makes it really hard. If the clay has any arc to it, like a rainbow for example, you’re going to have to move the gun in a similar fashion. That’s tough, because you’re swinging the gun on a horizontal plane, but also having to move it up or down depending on the trajectory of the target. Also, most clay birds have a point where they slow down, or an apex right before they start to lose altitude. If a clay does this in your shot window, that’s where you should break it.

If you’re used to covering up the target with your barrel in order to break it, that doesn’t typically work over 40 yards. You need to see some space or sky between the rib of the gun and the bottom of the clay bird. Bourjaily told me that if I covered up the target at distance it would cause me to miss high and behind. He was right. I was taught to cover up ducks with my barrel to kill them. It’s an effective method when birds are in tight, but it does not work at distance.

Read Next: The Three Best Sporting Clays Shotguns for Beginner, Intermediate, and Advanced Shooters

4. The Pull Away Shot

Some long-distance shots are easier to break if you use continuous lead paired with the pull away shot. You will keep the barrel in front of the clay bird as you do with continuous lead, and just before you are ready to break it, pull even farther out in front of the bird and fire. Make sure that when you pull away from the bird, that you do so in the direction it is traveling. For instance, if the clay is crossing right-to-left and on a slight descent, I look at the space to the left and below the bird (7 o’clock) and pull away. If the bird is a left-to-right crosser and rising, I look at the space to the right and above the bird (2 o’clock) and pull away. It’s a precise method that’s tough to master, so don’t worry if you struggle to find the proper lead. It takes time.

A word of caution for anyone who expect these tips to automatically make them a better shot at 40 yards and over: They won’t. As you practice, you’re going to get worse before getting better. And, if you’re trying these tactics and they are not working for you, stop. The shotgun swing is like a golf swing. If you keep repeating the same bad practices, it’s only going to impede your progress.