WE HAD FOUR DAYS TO HUNT. Just four fleeting days. In jail, I suppose, they’d have seemed pretty long. But if you’re a deer hunter, you know how short they were.

Every trick we knew failed. Hunting conditions were terrible. It was so dry that Idaho dust squirted up with every step and you could hear a grasshopper gnawing on a leaf half a mile away.

We were dog tired and as discouraged as a Republican in Georgia when we staggered into camp on the evening of the third day. The prospect of going home meatless next evening was about as cheering as running a spike through your best tire.

I was splitting wood and Burtt was peeling potatoes for supper when a pick-up truck pulled up beside our camp. A man stepped out and started to walk over toward me. I drove the ax into a log and straightened up, yanking out my handkerchief to wipe the sweat off my face.

Suddenly I recognized him in the dusk. It was John Smith, southwestern Idaho district conservation officer. I called Burtt and we shook hands all around.

Then John asked to see our deer.

“Deer?” I exclaimed. “What do you mean, deer? Aren’t you a bit previous?”

“Haven’t you boys got meat in camp—honest?”

“Not hide nor hair,” Burtt said. “We’ve hunted three days and haven’t seen anything bigger than a pine squirrel.”

“Too bad. But nobody’s having much luck. It’s so dry. Let’s see your licenses and tags and I’ll check them for you.”

After John initialed the licenses and handed them back, Burtt invited him to stay for supper, but he declined.

“I’ve got to check the rest of the camps along the river before the boys all go to bed,” he explained, “and I’ll have to hurry.” He started to climb into his pick-up.

“Wait,” Burtt said, “where can we find a couple of deer tomorrow?”

John tipped back his hat and rubbed his chin. “Where’ve you hunted?”

“Well, the first day we hunted on Granite Creek; yesterday we hunted in Ninemeyer Creek drainage; and today we hunted out the basin of that little creek that flows into the river just below camp here.”

“You haven’t hunted out Alder Creek?”

“No,” I said, “the hills looked so barren over that way that we didn’t try it.”

“Well,” John said, as he climbed in and stepped on the starter, “that’s where you’ll find your deer.”

When his tail-light disappeared around a bend in the road I said to Burtt, “Do you suppose John knows what he’s talking about? He’s a great kidder.”

“Can’t say. His finding out where we’d hunted and then telling us we’d find deer in the only place we haven’t sounded suspicious. Reminds me of the mining engineer and the tenderfoot.”

“What tenderfoot?”

“Why, the tenderfoot, fresh from the East and chock-full of innocence and optimism, who walked up to a mining engineer and wanted to know where to find a gold mine.

“The engineer was busy. He didn’t have time to give out with a lecture on prospecting. He eyed the dude up and down and saw the green sticking out of him all over. Wasn’t even any alkali dust on his boots.

“‘So you want to find a gold mine?’ the engineer said. ‘See that lone pine on the ridge over there across the canyon? You just go over there and start to dig in the shade of that tree. That’s the spot.’

“So the tenderfoot went and got him a brand-new pick and shovel. He struggled across the canyon and climbed the ridge. In the shade of the pine tree he started a prospect hole. About the time his hands were well blistered he hit a ledge of odd-looking rock. Didn’t know what it was. He couldn’t have told a piece of rose quartz from iron pyrites.

“So he had it assayed. It wasn’t gold, but it turned out to be rich copper ore—which is just as good if there’s enough of it. There was. In fact, the tenderfoot’s mine turned out to be one of the biggest producers in Montana.”

“Huh,” I said. “So you suspect, like me, that John was giving us the brush-off?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Maybe there are deer there. But it sounded queer to me.”

“I think we might as well try it. We couldn’t do any worse than we have the last three days.”

So next morning we had breakfast under our belts, lunches in our pockets, and were ready to leave camp just as the eastern stars were beginning to fade in the first streaks of dawn.

“Still think we ought to try Alder Creek?” Burtt asked.

“Might as well. But if we connect I’ll bet John will be as amazed as the engineer was when the tenderfoot uncovered his bonanza.”

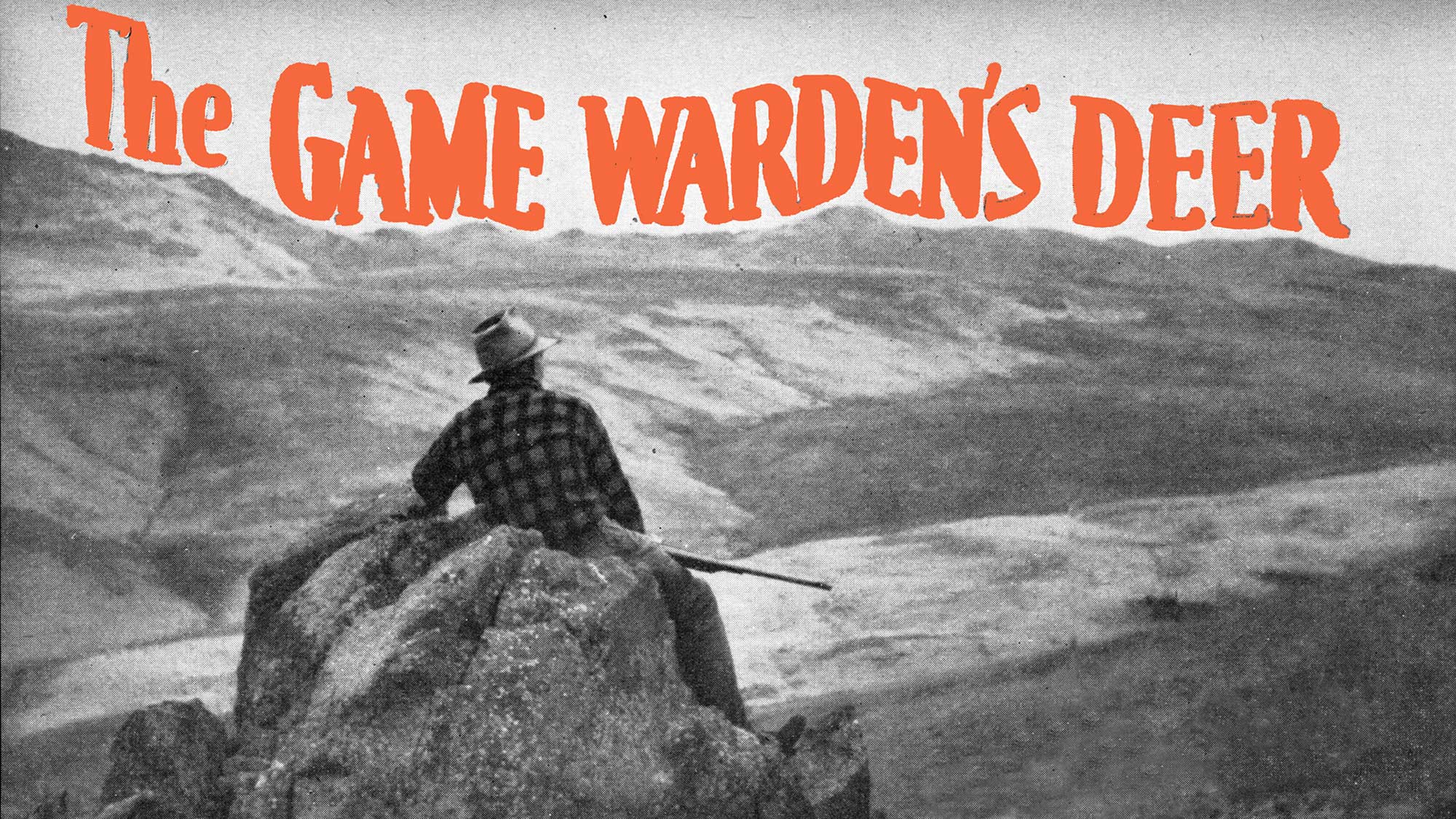

Alder Creek slips down a rather narrow canyon between barren hills, to empty into the Middle Fork of the Boise River about a mile east of the spot we had chosen for a camp site. We were hunting near Alexander Flats, a level patch of ground just big enough to whip a dog on, some fifty miles east of Boise, Idaho.

The slopes north of the Flats, toward the divide between the drainages of the North and Middle Forks, are ideal mule-deer country—when the deer are drifting downriver from their summer range in the Sawtooth Mountains. This trip, however, we arrived before the migration started. What few deer were in the region probably were residents which summered there rather than higher in the mountains.

We weren’t exactly oozing optimism when we crossed Alder Creek and started up the big ridge on the eastern side. Once we climbed past the first barren slope and could see up the creek, however, we discovered that the drainage was more promising than we had expected. The ridge shot up high near the river, then sloped down for several hundred yards to a low saddle before it started up again in toward the divide between the Middle and North Forks. The saddle appeared to be a natural deer pass.

There was a buck track in it, a track so big that Burtt gave a low whistle of amazement when he stooped to examine it. “This is fresh,” he said.

“Yeah?” I countered. “When it hasn’t rained for four months, how can you tell whether a track was made last night or last week?”

“Well, for one thing, there’s no dew in it, and no cobwebs. For another, the dirt hasn’t crumbled down around the edges.”

“Suppose it is fresh,” I said, “what good will it do us? You can’t trail a deer through even the first rocky spot when it’s this dry.”

“No,” he admitted, “you can’t. But it is encouraging. Maybe John did give us a good steer—and maybe it just happened! Let’s give this whole drainage the once over. There’s a chance the buck might be in it. If he isn’t, there might be other deer.”

“All right,” I said. “I’ll cross the creek and work up the west ridge. You take this one. Between us we can see the whole drainage. I’ll meet you on the divide at 3 o’clock—if I don’t get a deer first—and we can hunt out the creek bottom on the way back.”

Burtt agreed. I walked down to the creek, took a drink, and started up the opposite slope. I spent the remainder of the morning working up the ridge and inspecting the little brushy pockets, so favored by mule deer, that lay in under the roll of the hill.

There wasn’t a sign of a track crossing the ridge; apparently the buck had turned up the creek from the saddle. Noon came. I began to get discouraged. We had a short half day left.

I walked fifty yards out on a hogback from the main ridge, so I would have a better view of the creek basin. Here the draw fanned out in a grassy little flat on which frost-tinted aspens made splashes of vivid yellow.

I unwrapped my lunch, put it where it would do the most good, and smoked a pipe. Then, after carefully brushing away the duff to expose a spot of mineral soil—for the sake of safety—I knocked the ashes out, ground them into the dirt, and stood up. I had watched the draws, both north and south, and the entire drainage of the creek for half an hour. Time to find another vantage point.

For no reason at all, when I raised up, I carried a rock about the size of a baseball in my hand and gave it a thoughtless toss into the thicket, possibly fifty feet down the north slope from where I had been sitting.

The brush exploded when the rock struck. I caught a glimpse of a big, gray shape and a rack of antlers crashing toward the bottom.

That buck had lain there while I walked out on the hogback, ate lunch and smoked a pipe. He wouldn’t have moved at all if the rock hadn’t startled him out of hiding.

He was out of sight in the cherries before I could get my rifle to my shoulder. However, I knew that a mule deer, given a choice, usually will run uphill. Here the buck had three choices. Once he reached the bottom of the draw he could run downhill along it; up the barren south slope of the opposite hill; or up the draw and to my left. This last was his best bet; for at the head of the draw, 200 yards away, there was a thicket of fir. If he reached it he would have an excellent chance to escape.

Actually, I didn’t think of all that in the few seconds it took the big buck to crash through to the bottom of the draw. I sat down, wrapped the sling around my arm, shoved the safety off, and watched for him to break uphill along the bottom.

He did just that, running like Whirlaway in the home stretch. The bottom was clear of brush so he had free running, but he was partly screened by the chokecherries on the slope. I let him go until he came in line with an opening through the brush. Just at that moment he slowed down to look back. It was a fatal mistake.

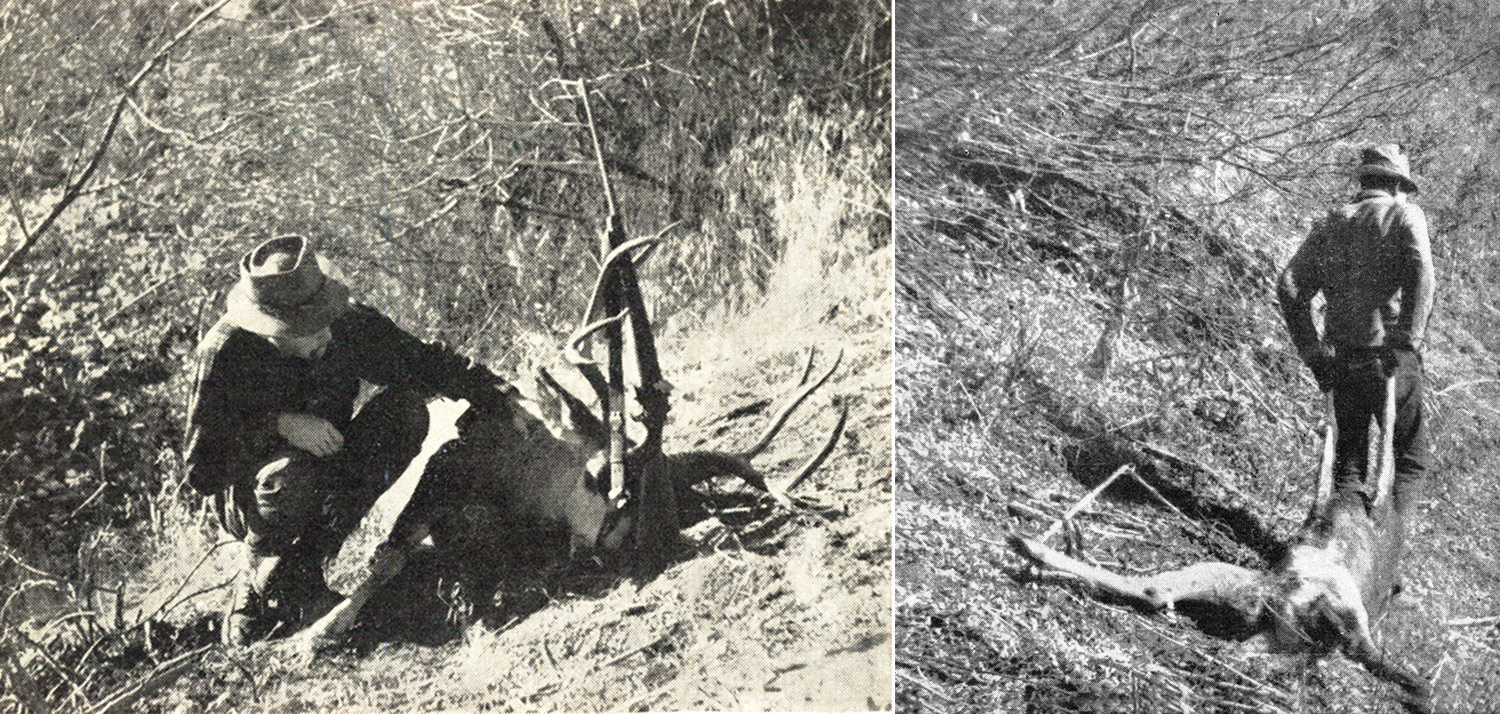

The .30/06 roared and he tumbled in a heap. He staggered to his feet and ran a few steps. I slammed another hull into the chamber and kept the rifle on him. But I didn’t need to shoot again. He toppled over gently and was through.

When I got to him, I discovered that he had a wide spread with four points on each side, but his antlers were rather slender.

I dressed him, sewed up the incision with a boot lace to keep dirt out, and dragged him down the draw to the shade of the aspens on the flat. I was so exhausted when I got him that far that I realized I’d never get him to camp in one piece I carried the heart and liver and my rifle to camp, then drove to the mouth of the creek and brought back an ax, my pack sack, and a tarp.

I skinned the deer out, split him down the back, and divided each side into three pieces. After wrapping the meat in the tarp to keep off flies, I hiked to the car with the head and hide. They made a pretty fair load. Then I carried the meat down in three more trips, stuffing just about all I could carry into the pack sack each time.

As I was walking up the creek for the last load I met Burtt coming down. He was dragging a big doe.

“Gosh,” I exclaimed, “I didn’t hear you shoot!”

“You probably were in camp with a load of meat. I saw part of your venison back at the flat. You must have got a good one. What was it?”

“Four-point buck,” I said. “But where did you get yours?”

“Up the creek. When I heard your shot I was nearly to the divide at the head of the creek. You only fired once, so I figured you got him. I hunted around in the basin at the head of the creek for two hours. There was quite a bit of sign, but I didn’t see any deer.

“Finally I gave up and started back. I picked the easiest route, right down the creek. I was pretty disgusted and was crashing along through the brush like a spooked steer when I heard a snort. “I stopped and looked around. Couldn’t see anything for quite a while. Then this doe started to run. She had been lying under some brush about 100 yards above the creek. When she heard me she snorted and stood up, but I didn’t see her until she moved again. I hit her pretty far back the first time and killed her with the second shot.”

It was dark by the time we got back to camp, where a pot of coffee and some deer liver and bacon and fried potatoes helped to revive us. We broke camp by lantern light and started home.

The Game Commission maintains a checking station on the highway a few miles east of Boise. When we pulled up beside it, John Smith and the deputy assigned to the checking job came out together. When John recognized us he asked, “Where’d you get your deer?”

“Right where you said.”

“That right? Hmmm. I knew you’d find ’em there!”

But he said something else under his breath. And unless my ears fooled me, what he said was, “Well, I’ll be damned!”

This story, “The Game Warden’s Deer,” originally ran in the April 1944 issue. Read more OL+ stories.