This story, “We Hunted off the Map,” first appeared in the April 1959 issue. It’s the third of Elliot’s stories from his time in Alaska, during which he also hunted Dall sheep and caribou. While it’s a classic big-game hunt of its era, this story also shows how hunting ethics have changed over the decades.

I PERCHED on the edge of a pannier, in fascination that must have been obvious. Paul Sloan, sitting cross-legged before the campfire, chuckled as he watched me. “You look like you’re about to grow roots into the ground,” he said.

Even that wouldn’t have surprised me. I wasn’t going to budge as long as Bill Boone kept talking. Bill was telling how he and Doc Johnny, his guide, had trailed their trophy bull moose and brought home its heavy-beamed spread, almost 60 inches from one tip to the other.

Paul and Bill, and John Harness, who completed our shooting quartet, are all Californians who’ve trekked through most of the big-game country on the continent. They’ve also hunted in Africa and Asia. I’m from Georgia and was on assignment here for Outdoor Life. I’d flown about 6,000 miles to meet the Californians on the northern rim of upper Yukon Territory, where we were to hunt in the most extensive wilderness I’ve ever encountered.

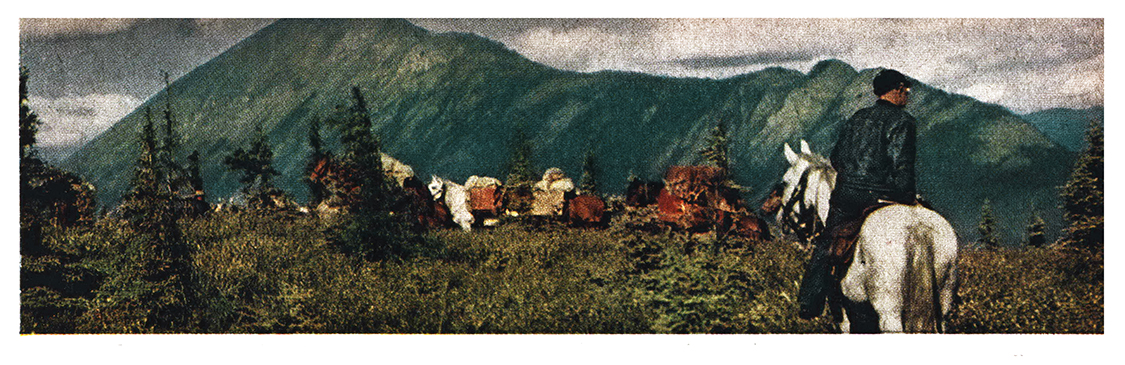

Louis Brown, of Mayo Landing, was our outfitter. With four guides and Vic (Frenchy) Poirier, our cook, Lou had traveled 10 days to bring his pack-string and saddle horses over the Mackenzie Mountain divide to hunt the north slopes which pour their waters toward the Arctic Ocean. We flew in from Dawson and met the outfit on a distant mountain lake that lies like a jewel in the massive ranges. In the three following weeks, we’d enjoyed one of the finest hunts any sportsman could hope for. We took four better-than-average Dall sheep heads, three caribou, and two grizzlies. Now Bill Boone had come up with a magnificent moose head, and his campfire re-enactment of the hunt was doing things to my blood pressure.

“Start over—at the beginning,” I begged, “and don’t skip a detail.”

For three days, said Bill, Doc Johnny and he had stayed on the track of the bull moose like a couple of famished wolves. It was along the rim of a muskeg bog that they first discovered his prints—wide, deep impressions that made the veteran guide pause and push back his cap.

They trailed the bull along a well-defined trail from an old salt lick above the Bonnet Plume River to where the tracks disappeared in spongy muskeg. From that point he could have gone any direction. The land was a crazy quilt of bogs, shallow ponds, and rocky backbones. One whopping ridge, with scattered spruce around its base, paralleled the river. Between this isolated height and the main ridge which climbs skyward through timber, brush, moss, barren earth, and rock, sprawled about a mile of muskeg. This flat, several hundred feet higher than the river bottom, was carpeted with knee-deep moss, and dotted with trees and small lakes.

When the moose trail disappeared in the moss, it seemed to be leading toward the main range, so Bill and his guide came back out of the muskeg to the big ridge, tied their horses in the timber, and climbed to where they could watch the broad sweep of mountain beyond the muskeg flat.

They kept their vigil for most of a day; early that evening the long wait paid off. They spotted two bulls in a willow clump several hundred yards up the mountain. The animals were too far away for proper evaluation, even through 8X glasses. Though the time was 7 p.m. and they were a good three hours from camp, they decided to cross the muskeg for a closer look. Johnny was reasonably sure one of these bulls had made the outsize tracks.

Leaving their horses at the foot of the ridge from where they’d spotted the moose, they slogged across the mile-wide mire on foot. Circling to get downwind, the hunters climbed the slope, working through thick willows and alders to within 150 yards of the animals. From that distance, Bill peeked through the brush at the biggest moose he’d ever seen. The antlers were still partly in the velvet and slightly ragged around the edges, which made them look immense.

Bill crawled a little farther up the hill to an open spot where he could sit and squeeze off a shot. They heard the 180-grain chunk of lead hit the huge animal’s shoulder. The bull hardly quivered. He simply took a couple of steps, as if to walk away. Bill squeezed off another shot, which hit inches from the first. He might have slapped the moose with a fly swatter for all the effect it seemingly had. The big animal continued to walk. Even Doc Johnny was awed.

“He can take plenty of punishment,” he whispered.

Bill held steady and tried for a neck shot with his .300 Weatherby Magnum. His first 180-grain Nosler bullet was backed by a series of 150-grain leads. His third slug, in the bull’s neck, put the big animal down for keeps.

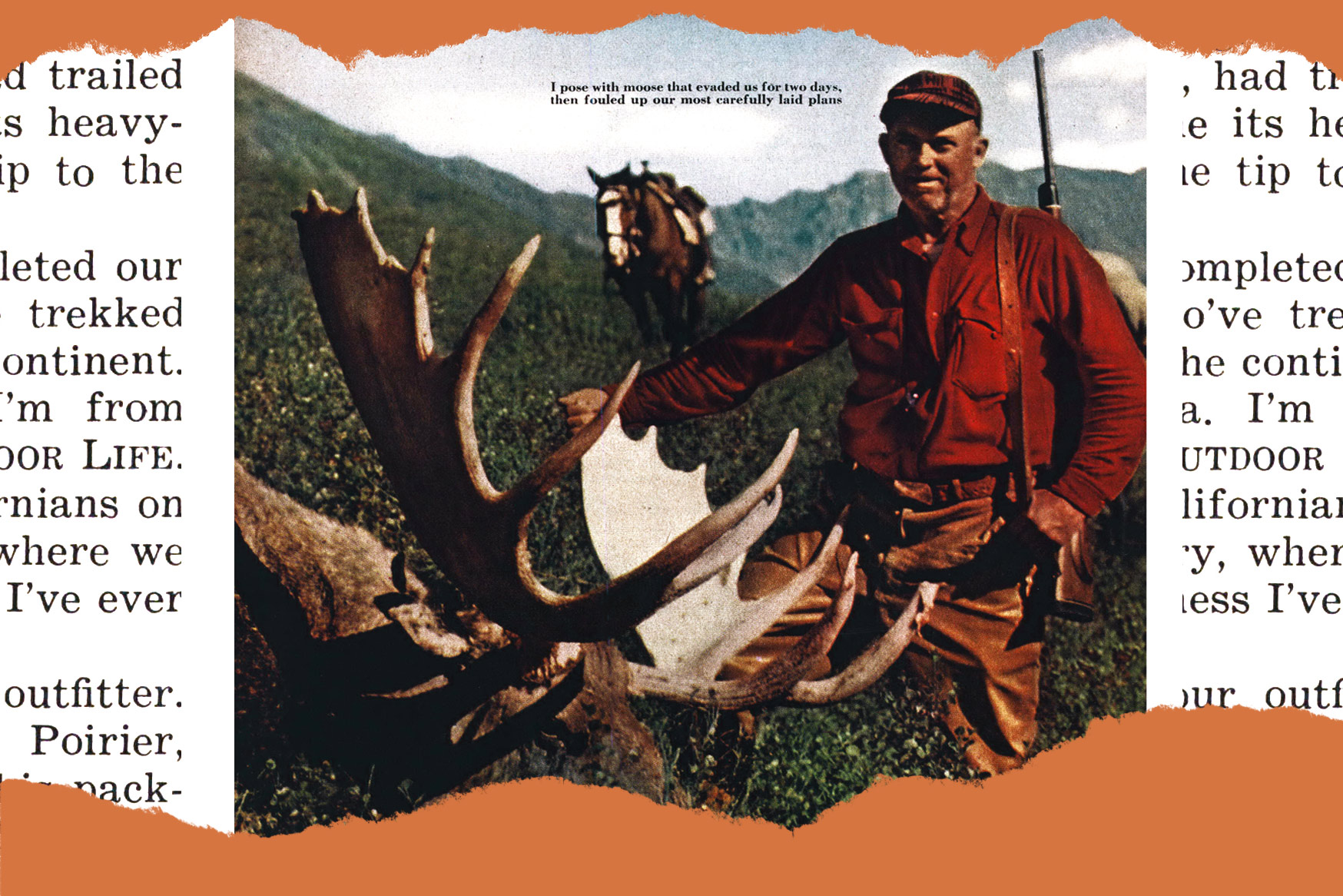

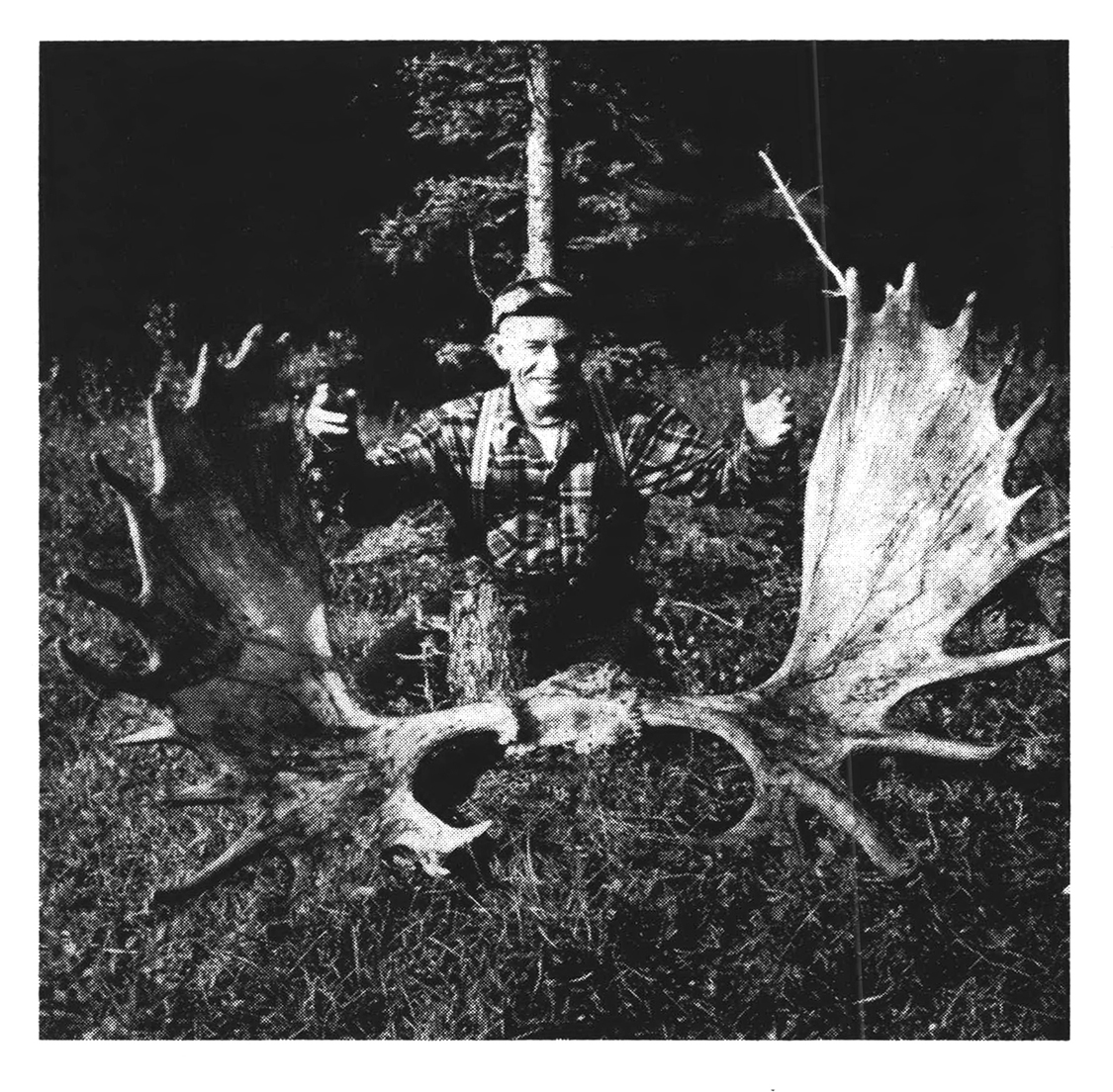

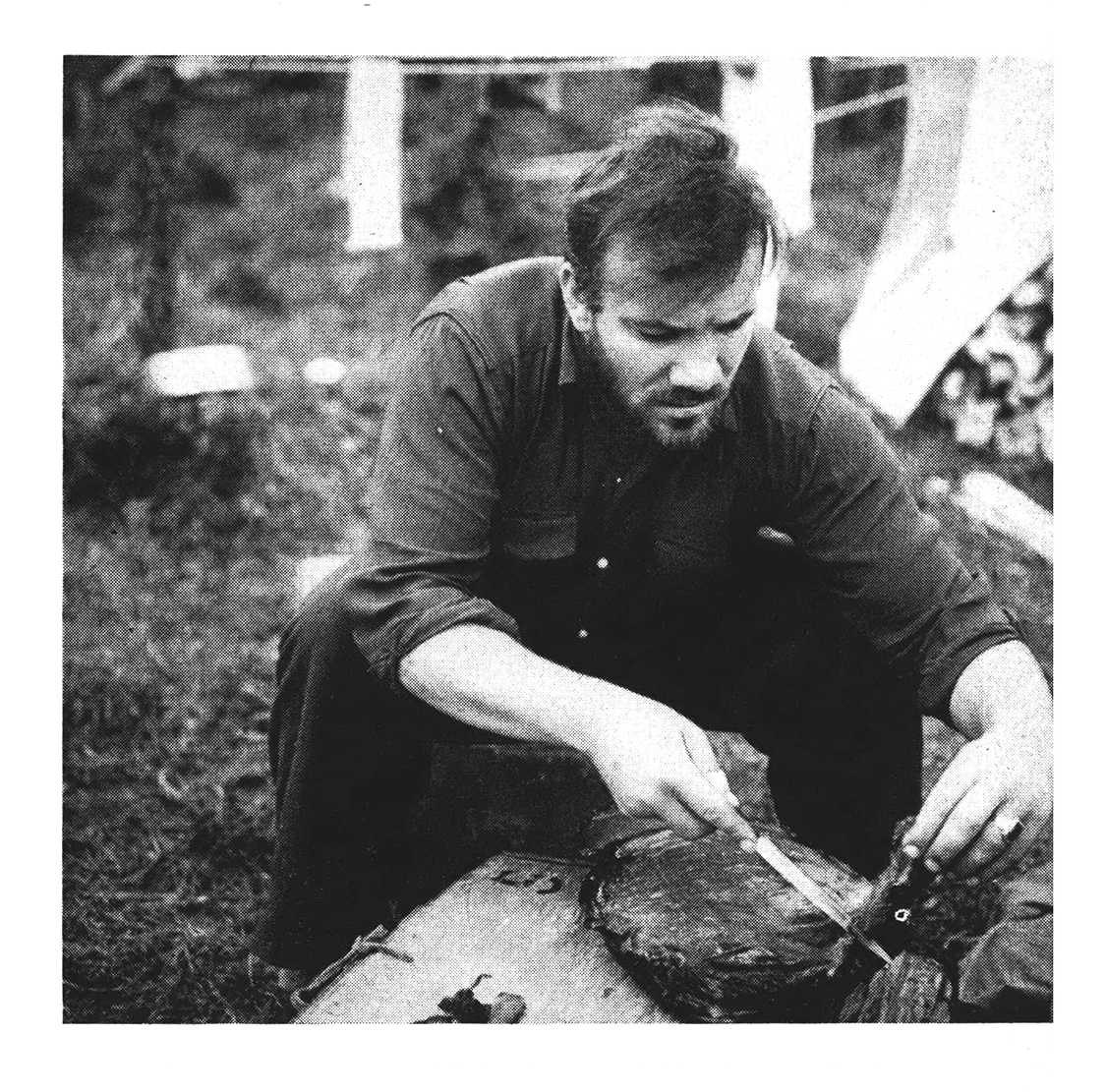

My hunting partner swore he was as proud as anything when he walked up to his trophy. Johnny had a tape in his hip pocket, and before he began to whet his hunting knife, they measured the spread of the green antlers. The rack was just under 60 inches; the palms were huge-35 inches long and 14 wide, with 28 points.

Bill and his guide didn’t try to cape out the animal that night, but merely field dressed it to pick up the next day with extra horses. They crossed the bog again and rode into camp around midnight.

I was already impressed with the magnitude of the country we were hunting, but it was during my search for a good moose head that I realized how fruitful and lush it is during its few weeks of summer. The massed vegetation grows literally with its roots in the ice. The ground never thaws more than three or four feet down, and yet the summer land is luxuriant in its production of fruits and succulent sprouts and grasses. The valleys and mountainsides produce bumper crops of blueberries, cranberries, and wild currents. Willow sprouts grow several feet tall, and grass and reindeer moss carpet the earth above where the shrubs run out.

From the time the plane set us down on a small lake near Wind River, to the end of the hunt, we covered a rough perimeter of 100 miles, spaced with five camps. For most of this country close under the Arctic Circle, we had maps. Then one day we rode off the map and were on our own. Lou and his guides had hunted this country three years before, though, and were familiar with the land’s general pattern.

John Harness and I decided we’d like to make a fly camp away from our main base of operations. Our outfitter, Lou Brown, would guide John, and Paul Germain would be my guide. Setting up such a side camp in that land, merely to see game, is somewhat like riding from Brooklyn to Manhattan in New York to look at traffic. But we figured it would be a change of pace and give us longer to hunt. Lou suggested the long valley of Pops Creek. Lou had labeled that one himself—just as he designated all places in that country that he wanted to remember for some special reason. Ronnie Pops, widely known Vancouver sportsman and taxidermist, had gone into the area with him several years before and had brought out some magnificent trophies.

WE PACKED a couple of horses with sleeping bags, tent, extra clothing, and enough food for a couple of days. We were climbing into the saddle when Frenchy, our camp cook, walked out of his tent.

“You’ll bring back some meat, maybe?” We promised that since our supply of wild steaks, chops, and roasts was low, we’d do our best.

We crossed the Bonnet Plume River, wound through lowland forests of spruce, and worked our way upriver to Pops Creek. Even to one gorged on scenery, as I had been for weeks, the canyon was spectacular in its massive and rugged spread. It dwarfed even most of those I’ve seen in our stateside parks, which are preserved primarily for their natural beauty. And since Lou and Ronnie Pops had hunted here more than four years before, as far as we knew, no human had left a bootprint in the place.

“I wonder how long this land will stay virgin,” I said.

Lou told us that already there was talk of a military road over the ranges and down to the arctic coast.

We rode most of the day, looking at bands of sheep high under the rims, and watching for grizzlies feeding above timberline on the bold slopes rising from the creek. We stopped to look at many game heads, but saw nothing outstanding. At the last main fork of the stream, we climbed a long, wooded backbone to a shoulder of the mountain, where the timber ran out in scattered, scrubby trees. As we dismounted to make camp, a rainstorm swept the mountain, whipping through the trees and blotting out the big land around us.

We unloaded our horses and pitched the tent in as level a spot as we could find. My guide located one of those eternal spring holes in the muskeg-downhill 100 yards—and we collected wood for a fire. The rainstorm moved on, the sun slipped behind the massed mountains, and an icy wind whipped along the slope.

Before we blew up our air mattresses, we took time to glass the slopes around us in the fading light. Two small bunches of caribou, first of the migrating horde, dotted both sides of the creek valley. They were brown specks moving against the green hills.

Through his glasses, Lou spotted a bull moose almost a mile away, across one of the creeks. We all had a look.

“At least he’s big enough to rate a good once-over,” the outfitter commented.

White sheep fed across the face of the mountains on three sides of us. Beyond the main valley from camp, we counted more than 30, browsing along an almost-vertical slope. Lou dug his 20X telescope out of a saddlebag and used it until the light grew too dim.

“All I can make out,” he said, “are ewes, lambs, and small rams.”

WE ENDED the day with a pot of tea over a roaring fire, which dried our rain-soaked clothes and provided heat for a frying pan full of caribou slabs and mushrooms.

I had already crawled into my sleeping bag when John came into the tent. With hands on hips, he regarded me for a moment and laughed.

“You gonna sleep standing up?”

I felt that way, too, for our campsite was so slanted that my feet were 30 inches lower than my head. Lou came over from the campfire and stuck his head in the tent flap.

“If you wake up in the creek,” he said, “wash your feet and come on back for breakfast.”

Rain was pattering against the tent when I came to life again. Paul had a fire going and coffee water on. The rain was cold and slanted down the mountain.

“It’s a good day to stay inside and read,” John yawned, “if we had anything to read.”

Shortly after six o’clock, my guide and I saddled up and rode to one of the misty valleys we’d crossed late the afternoon before. We were at the edge of timberline, and the wet brush soon had us soaked to our belts. We followed the contour of the hillside, stopping to glass a ewe and lamb that grazed complacently not more than 200 yards above us. Looking through my binoculars, Paul Germain muttered the longest sentence I’d heard him make.

“Little sheep—they’re coming far down the mountain. The big rams are staying on top.”

As if to verify his observation, I spotted a big Dall ram on the skyline, lying in the V of two long slopes, where not even a cony could have approached unnoticed. Farther on, we stopped to examine the fresh print of a grizzly, and moments later the Indian slid off his horse.

“Bear. He’s going over the mountain,” he said. I saw the hind end of a grizzly disappearing beyond the skyline. He was making tracks—fast. We talked it over. The animal hadn’t seen us and the wind was in our faces, so something else must have startled it.

“What would spook a grizzly ?” I asked.

“A big moose, maybe,” Paul grinned. “But it must be big.”

We hunted out the canyon for the rest of the day, and spotted only two moose—a cow and calf-feeding in the willows of the creek bottom. We tried to stalk close enough for a picture, but mamma got our wind and dodged through the deepest part of the thicket. Then we tied our horses and climbed a tremendous hunk of ridge where we sat and glassed a pair of valleys until two hours of late-afternoon rain drove us back to the horses.

The sun set clear and cold. That night we got a good frost with a touch of ice. Before Paul had built his breakfast fire and put on coffee water, Lou walked to the rim of the hill above timberline to glass the slopes. He came back with the information that our moose was in the same spot where we’d discovered him two afternoons before. Over coffee, we decided that since we had only a 20- to 25-mile ride to our main camp, we’d have enough time to look the bull over at close range and decide whether he was in the trophy class.

While they completed the job of breaking camp, I walked downhill with my glasses and rifle. Walk is hardly the word for it. Like most of those arctic slopes, this one pitched away from camp at about the same slant as our tent roof. Without the alders, willows, and scrubby spruce to hold me up, I might have gone headlong off the mountain. I worked my way directly across the canyon from the moose, and through my 8X glasses got a good look at his head: it looked massive.

According to our agreement before I left camp, I waited in the creek bottom until Lou, John, and Paul brought the horses down and tied them in the timber. From the bottom of the canyon, we mapped our strategy.

We weren’t quite close enough for a certain kill, and if we boldly climbed the slope to the patch of timber where he lay, the moose would most certainly slip away. We decided that I should remain in the canyon, Paul would stay with the horses, and Lou and John would cross the creek and climb the mountain on the downwind side of the moose. They were to go around and approach him from above. When the bull spooked, he’d either climb above the timber and be an easy target for John, or come downhill toward the creek where I waited. We figured that under this arrangement, he didn’t have a chance. The bull had other ideas.

I sat with my back against a frosty boulder on the canyon floor for three-quarters of an hour while they made the climb. I could catch only occasional glimpses of the hunters pulling themselves by handholds up the brushy slope. At other times I marked their progress by the shaking undergrowth of alders. I also watched the spot where I’d last seen the moose.

He must have gone out of there like a furtive cottontail, carrying his big rack low. Through the glasses, I suddenly discovered him standing 100 yards from where he’d made his bed, on the same contour. He was looking over his shoulder at the two hunters who had approached him upwind. By all our calculations, he should turn downhill, directly toward me. So I held my fire and waited.

For five minutes he stood motionless. My hunting companions who’d moved in from the hill didn’t see the bull. I could tell that from the way they continued to advance, stopping to peer through the foliage. There was no way I could signal them, so I remained motionless to see what would happen. When the moose moved, he didn’t come toward me, but turned up the hill.

I realized then what a long flight my bullet had to make. I was using a variable scope and turned it to 8X. I guessed my distance was about 400 yards. But with the bull pointing up hill, I didn’t want to take the chance of spoiling a ham or shooting off one of his antlers. So I held my fire until he stopped and turned broadside.

HE LOOKED almost too far off for my .300 Kennon Magnum, but I tried it anyhow. I held just over his back and squeezed off a shot. The bull looked down, as though annoyed, and I figured my 180-grain Core-Lokt was low. Holding a little higher, I tried again. The moose stumbled slightly, but didn’t go down. I later learned that my first lead cut a piece of meat out of his leg below the knee and the second, a chunk out of his brisket. He turned at an angle toward John and Lou. My third shot, held over his shoulder, plowed into his jugular, but didn’t stop him.

He was almost 200 yards away from my two hunting partners, and bleeding profusely. Lou could visualize a day of tracking him through the brush and maybe finding him in some distant canyon, which would mean an all-night ride back to our main camp.

“Better see if you can stop him,” he said to John.

I was too far away, of course, to hear the conversation. But through the telescope sight, I watched John swing, and saw the hair puff up where his bullet struck just under the backbone at the top of the bull’s shoulder. The moose paused, stood a moment, then went down.

With mixed emotions of elation and uncertainty about whether I could even claim the kill, I walked back to Paul who was keeping watch over the horses. We untied the pack animals, swung into our saddles, and made the steep climb to where the bull had gone down. Lou and John were there ahead of us, and John stuck out his hand.

“Congratulations on a great shot.”

“You’re being a gentleman,” I said.

“It’s your bull,” Lou put in. “He was dead on his feet. We just didn’t want to climb any farther up this mountain than we had to.”

The bull looked even bigger than he’d appeared in life. Elation warmed me to my toes. Then I showed what a tyro I really was by swaggering completely around the animal before we put a tape on its 55-inch spread and made pictures.

John and I squatted on our haunches while Lou and my guide Paul, dressed out the animal. It was a neat process, in which they saved all the meat but one shoulder.

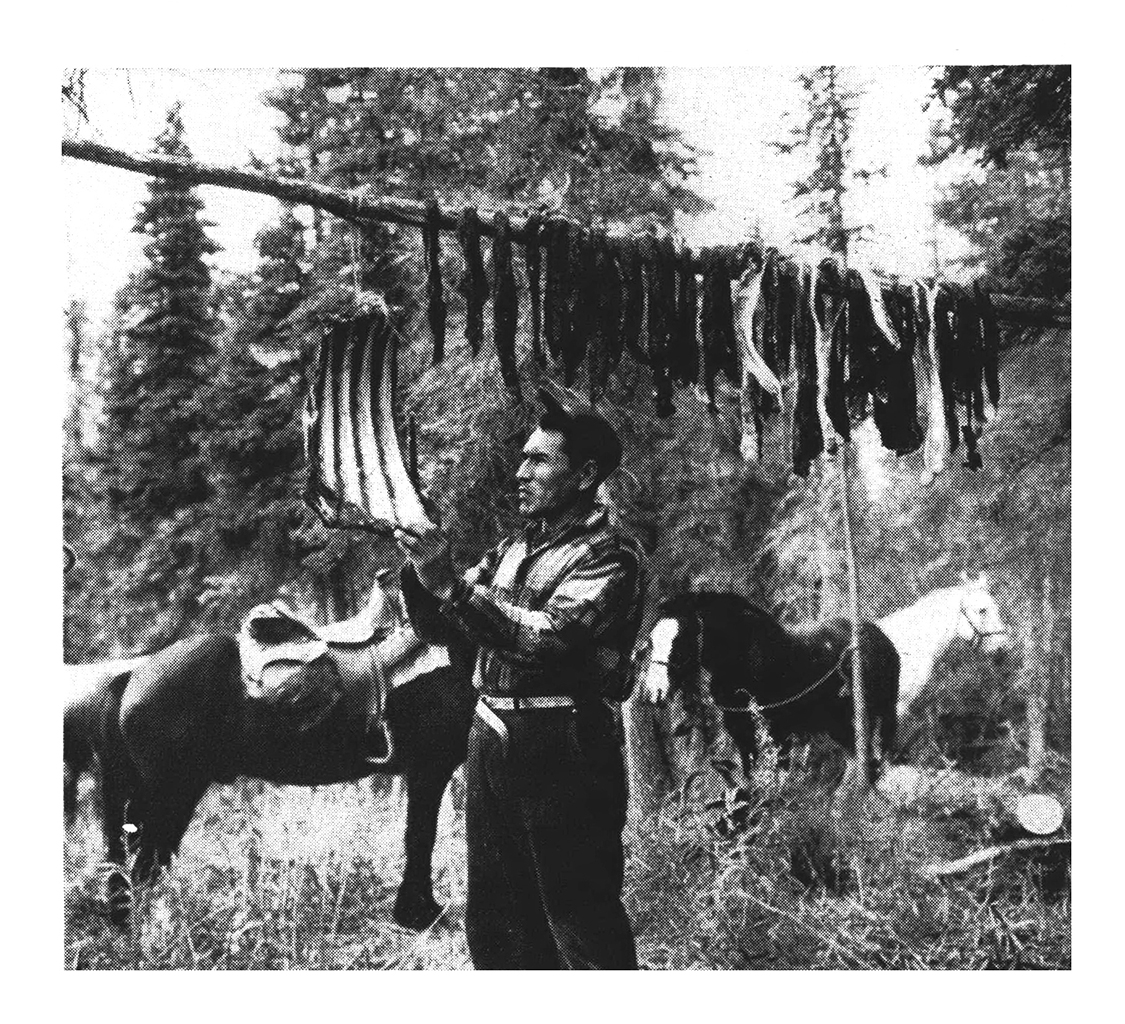

As with all of our game kills, they prepared every edible bit of meat to be packed into camp, where most of it was hung on racks to cure. The Indians made jerky out of a portion of each kill, hanging strips of it in the sun over a light smoke to dry. I could never quite decide whether moose meat was more delicious than sheep or caribou, or even whether Frenchy’s moose steaks were tastier than the strips of jerky roasted over a campfire.

Paul wore a pleased expression as he wielded his knife. We’d hardly packed in enough grub for two days in the fly camp, and were already short on rations. That morning for breakfast, Lou had divided a cup of cereal among the four of us, and then packed a chunk of bread and piece of cheese for lunch. We finished dressing out the bull and Paul asked the question that was inevitable after each kill: “We can build a fire now? And make tea? Roast a rib?”

Camp was 20-odd miles away, with the Bonnet Plume River to ford. Lou voted him down, with the promise that we’d haul those ribs along and cook them over a campfire the next day. We did, too. But that noon it was sure a disappointed and meat-hungry man who boarded his horse for the long ride to Frenchy’s well-stocked larder in the cook tent.

This text has been minimally edited to meet contemporary standards.