If you’re not careful, you’ll use up a whole summer eating barbecue, drinking beer, and fishing. Too much of that stuff will soften your shotgun swing as much as your belly. Next thing you know, it’ll be opening day of duck season, and you’ll make an ass of yourself by tearing through three boxes of shells and not cutting a feather. Picking up a shotgun in the off-season does you good.

Fortunately, there’s a world of wingshooting opportunity available all summer long, from feral pigeons and invasive Eurasian collared doves to crows and early-season geese. The action can be intense, and once it’s over, some of the birds are pretty good to eat. Which brings us back to beer and barbecue. It is summer, after all. —W.B.

Crows

Back in the 1930s, crow shooting was as popular as hot dogs at the ballpark. There were so many birds that fish and game agencies gave farmers free shotgun ammo to defend their crops. In Oklahoma, there was a full-on propaganda campaign to promote crow as a healthy and delicious game meat. Crow-hunting clubs popped up around the country. But eventually the Great Depression ended, and crow fell off the menu for most folks. Wingshooters moved on to more glamorous pursuits, and these days calling and decoying crows is done by a relatively small but dedicated group of bird hunters. Which means there’s plenty of room for you to get in on the action.

Crow seasons vary across the country, but whenever and wherever you chase them, you’ll still find farmers willing to grant you hunting access.

These birds like to feed on sweet corn, and typically pick off the tops of the cob, which makes the entire ear of corn unharvestable. Crow season gives you a chance to build a good relationship with local farmers that could lead to hunting opportunities later in fall. Plus, it’s just flat-out fun.

When Virginia’s early crow season opens in mid-August, Jamie Tomlinson gets after them. On a typical day, the 26-year crow-hunting veteran will shoot 10 birds in a morning. But on a hot hunt, he and a couple of buddies will bag 35 to 50 birds. Here’s how he does it.

Setting the Trap

Tomlinson focuses on finding food sources near crow roosts. In his area, that often means cornfields farmers have cut early for silage, or silage pits where farmers store their corn. He hunts early mornings, before the midday heat, and sets a spread of about 12 full-body decoys. Tomlinson can usually find green summer foliage to hide in, but if farmers have hay bales wrapped in white plastic, he’ll throw on a white painter’s suit and lean against a bale.

At first light, start working crows off the roost with a mouth call, Tomlinson says. The goal is to attract only a few birds, not the whole mob. “They’ll come in one and two at a time, see the decoys, and think there’s food,” Tomlinson says.

When the initial flights slow down, Tomlinson gets more aggressive and switches over to his electronic call to imitate a group of crows competing for food. Crows are typically in smaller family groups now—you won’t see the giant murders of 100 birds or more like you might in winter—though occasionally he’ll work in flocks of about 25 birds.

And yeah, believe it or not, crow is definitely edible. You can find a killer recipe at outdoorlife.com/blackbirdpie. —B.L.

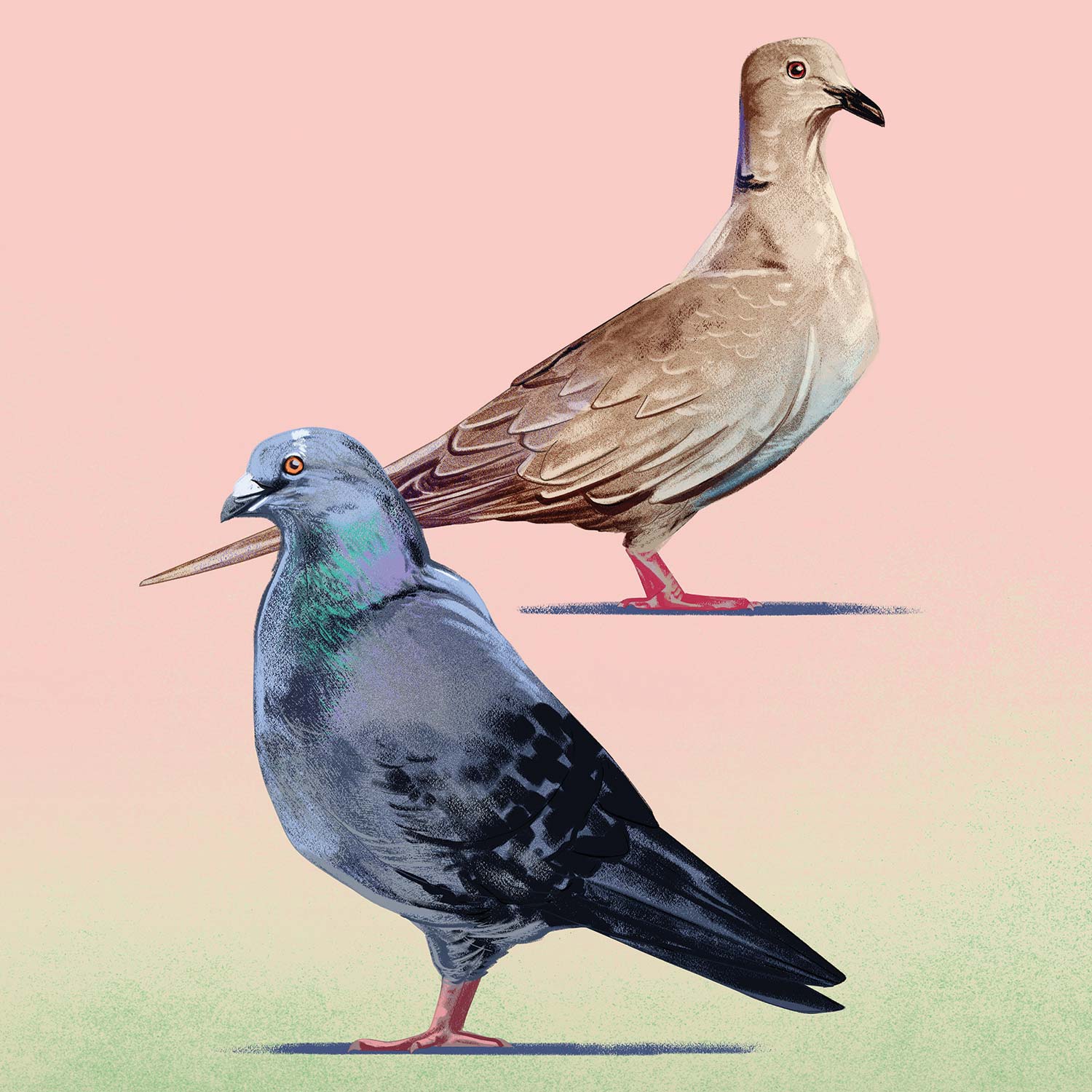

Pigeons and Collared Doves

I could’ve confused the affair with a dry-field duck hunt. Wayne Bolt, owner of Avian Expeditions (avianexpeditions.com) in the Texas Panhandle, had been scouting birds for days before we arrived. We set six-dozen full-body decoys on the X in the dark, flicked on half a dozen spinners, brushed in a blind, and hid ourselves.

“The big flocks will be coming in from town here in the next 20 minutes,” Bolt said.

He was right, though I don’t know that it took 20 minutes. My hunting buddy Terry Denmon, owner of Mojo Outdoors, had promised that I’d enjoy shooting feral pigeons over decoys.

“They circle and work like mallards,” he said.

He was also right. Swarms of birds appeared, setting their wings in tight Vs to dive-bomb our spread. After a few missed volleys at 10 yards, Denmon and I decided that we needed to adjust the spread out away from the blind a bit, to allow our patterns to open up. Bolt laughed: “Getting them too close for you guys, eh?”

Yep. We might’ve been a little rusty too.

We burned through a case of 20-gauge shells in a few hours. We were hunting early spring, shooting over a feedlot, but you can hunt pigeons year-round. In June and July, farmers begin cutting wheat fields, and pigeons swarm to them to clean up the waste grain. The outings become even more like waterfowl hunting then, with most of the gunning done from layout blinds or brushed-in stand-up blinds.

Pigeon Perfect

Feral pigeons live just about everywhere, but they’re especially prevalent near livestock operations, where they can roost and nest in dilapidated barns, silos, and storage buildings.

Bolt scouts hard for birds trading from these roosting areas to feeding areas, and many of his clients have come to prefer high-volume pigeon shoots to the waterfowl hunts that he also sells.

“The first time you hunt a new bunch of pigeons, you can stand in the field wearing blaze orange and it won’t much matter,” Bolt says. “But they learn fast. Pigeons are highly intelligent—they were trained to carry messages in World War II. You can still have a good shoot from an educated flock, but you have to change things up. Complete concealment in a layout or stand-up blind is mandatory.”

Dead birds make great decoys. “When I’m hunting a lot, I try to keep 18 to 20 fresh-killed pigeons on hand to use as decoys,” Bolt says. “If I don’t have any, I use full-body decoys. But real birds always outperform plastic ones.”

Motion decoys are lethal on pigeons. On a new field, Bolt will start with a single Mojo Dove, but as birds become more educated, he’ll add more movement to his spread, including multiple dove and pigeon spinners set on stakes, and small Dove-a-Flickers (each has a single spinning wing set on a timer) scattered throughout the spread.

Bonus Birds

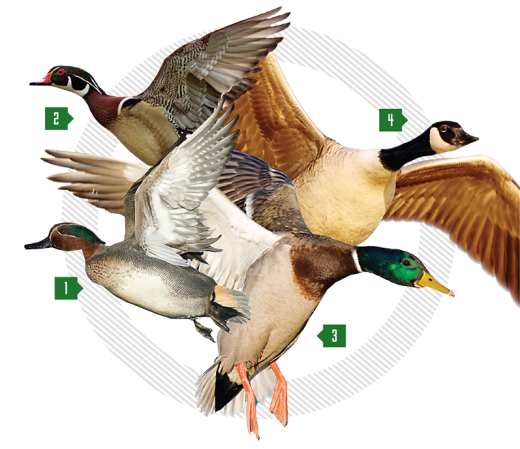

You’re likely to see Eurasian collared doves on a good pigeon shoot—we certainly did. These birds are similar to mourning doves in many ways (they’re pretty damn good wrapped in bacon too). Adults sport a black ring at the nape of the neck (hence the name), and they make a harsh, distinctive reeaaa call. For hunters, the most important difference is that collared doves were introduced into the U.S. by mistake in the ’70s, and have colonized so quickly that they can now be found all over the country, with the exception of the Northeast. They’re considered an invasive species, and in most places, you can hunt them year-round without a bag limit. But on a summer pigeon hunt, you must be absolutely confident in your dove ID. Blasting a mourning dove by mistake during a pigeon shoot in July is a serious game violation.

“First thing I tell my clients is, if they’re not 110 percent sure that it’s a collared dove, don’t shoot,” Bolt says. “A mature Eurasian dove is big, the size of a feral pigeon. A mourning dove has a pointy tail, while a Eurasian dove has a blocked one.”

The birds have different flight patterns too. Mourning doves are legendary for their shifty, left-to-right movements that cause most wingshooters to blow their shotgun-shell budget. But Eurasian doves tend to fly at a constant pace, staying on a straight flight path. But fair warning: Eurasian doves are blazing fast, and it’s still entirely possible to miss them. —W.B.

Early Geese

Late-summer geese might seem like easy targets—the birds haven’t been pressured since winter, early bag limits are generous, and there’s often less competition from other hunters. But don’t be fooled. These local birds have the home-field advantage.

Joe Fladeland, an avid North Dakota waterfowler, has hunted the state’s early goose season since 2005. That hunt opens August 15, but even if you can’t make it to NoDak for the earliest goose opener in the country, Fladeland’s tips can be useful on your own hunting grounds. Many states offer an early honker season in the first weeks of September.

“Geese are still in fairly small groups at this time,” says Fladeland, a pro staffer for Field Proven Calls, Banded, and Avery. “You’re looking for groups of 100 or maybe 200. For the most part, they haven’t even thought about migrating yet. They’ve just gone from individual family groups to maybe 10 families.”

Seek and Hide

Summer geese aren’t locked into rigid feeding patterns and don’t have to compete for food, which can make it tough to locate the X. Fladeland starts scouting for local geese a couple of weeks before the season, keying on freshly harvested ag fields—typically peas, oats, or barley. He targets fields that are far from roosts so birds must fly in rather than simply waddling over to feed. Lazy summer geese have a habit of walking right from a roost pond to a field to feed.

“Stay on top of them and monitor their activity,” Fladeland says. “I’ve watched fields of geese for two weeks before the season thinking we would be in for a great hunt, and then two days before the season opened, the geese switched fields and split into multiple groups. A field of 450 can become three fields of 150 really quickly.”

With a promising field located, Fladeland focuses on his hide. Layout blinds are best, but some situations—such as a cut oat field that offers no cover—make that impractical.

“It just depends what you have for a field,” he says. “If the field is carpet-low, you might have to shift to the edge cover. If there’s a little dip where the combine couldn’t cut, you can put your blinds in there.”

Even when using layout blinds, Fladeland augments his hide with natural cover by raking up as much stubble as possible. The key is to gather stubble and natural vegetation from areas that are away from the blinds, otherwise you just end up creating a visual accent around the blinds.

“I’ll fill a truck bed full of stubble and use it between the blinds,” Fladeland says. “I’ll even try to level it out so you don’t have humps where the blinds are.”

The number of decoys Fladeland sets depends on how many hunters he’s trying to hide, but in general, you need fewer decoys early in the season than you do later. Five hunters call for a 100-decoy spread, but a good hide with only two layout blinds requires just three dozen full-bodies.

Read Next: The Best Hunts of Summer

Capture the Flag

Fladeland doesn’t go heavy with calling during the early season, because summer geese are not as vocal as migrating birds. Instead, he relies more on flagging to attract honkers and guide them to his setup.

“Once I can tell that they see the spread, I flag at them to get them headed my way,” he says. “If they start to set down too early, or if they start swinging, then I’ll flag at them aggressively.”

When the geese lock on to the spread, or if they’re going to slide by inside 50 yards, drop the flag and get ready to shoot. —B.L.