The way Dan Harrison sees it, the “Keep It Public” movement gets it doubly wrong when it comes to state school sections.

First, school trust lands aren’t public, he says, in the same way that federal Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management lands are. Second, the rising interest in public accessibility to these lands is relatively new, and contrary to the origin and purpose of this class of property, which cover some 43 million acres across the Western states.

As you might imagine, given the passion that public-lands advocates pour into voicing their interest in gaining, improving, and perpetuating access to public lands, Harrison’s opinion is heresy.

But Harrison, a big-game outfitter who lives and operates in western Colorado, says both history and on-the-ground consequence of these lands resist the “Keep It Public” rallying cry.

“These are not now, nor were they ever, established as publicly accessible lands,” says Harrison. “They were intended as a savings account for the states to fund schools and public education. The main purpose of the state trust lands is to generate revenue for the state, not to give hunters additional places to hunt.”

But Joel Webster, the director of the Center for Western Lands, a project of the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (TRCP), claims history is also on the side of those who maintain that state trust lands represent some of the best hunting and fishing destinations in the West (while keeping in mind the public purpose of our collective property). In many ways, both Harrison and Webster are correct; the difference is that Harrison is looking backwards at the origin of these lands; Webster is projecting forward, to an evolved way of considering how we value them.

What’s brought the issue to a head is a very modern way of analyzing the quantity and distribution of state trust lands.

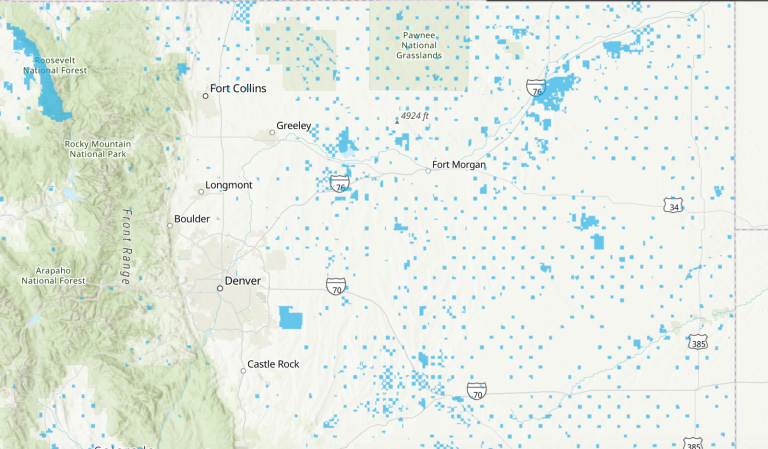

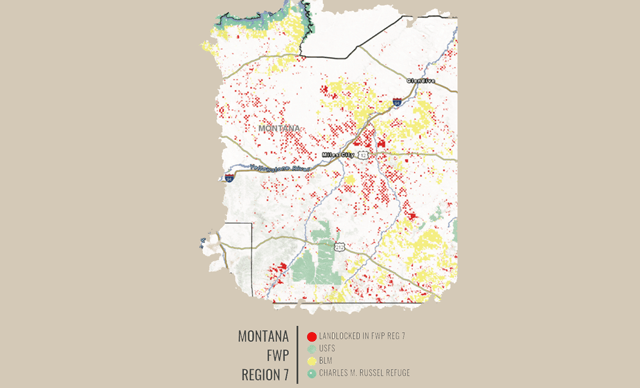

This summer, the TRCP teamed up with the digital mapping service, onX, to research and distribute the “State Landlocked Report.” The report identified 6.35 million acres of state lands in 11 Western states that are largely inaccessible to hunters and anglers because they’re surrounded by private lands.

“You’ll hear that states established these trust lands in order to generate revenue for a specific purpose, whether public schools or land-grant institutions,” says Webster. “That is their common history. But over time, states have come to recognize that the public purpose of state lands transcends just maximizing annual receipts from grazing or mining or timber harvest. They’ve defined the longer-term benefits as more sustainable, contributing to improved water quality, wildlife habitat, viewscapes, and public recreation.

“Are state lands public?” asks Webster. “It depends on the state, but in at least seven Western states—Washington, Montana, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho—the constitutions define state lands as public.”

Four states—Nevada, California, Arizona, and Oregon—do not define either the status or public purpose of school-trust lands.

Still, says Webster, these lands are owned by the people of the state, and not private entities. That makes them public by definition. It does not, however, make them multiple-use lands automatically open to hunting and fishing.

The Revenue Mandate

Most federal lands do not intend to turn a profit. Land managers receive an annual appropriation from Congress, and while they’re happy when receipts from grazing or logging subsidize capital projects in their areas, they recognize that all the multiple use that happens on federal land—from mining to horseback riding to hunting—is subsidized by the citizens of America. That’s one argument for public access to these public lands: the public pays for them.

State lands, on the other hand, were expressly created to generate funds. While both sides of the accessibility question can argue about history, the origin story of these state lands is clear: they were established primarily as a way to fund public institutions. This revenue mandate can both confuse and compliment the accessibility argument. Again, both Harrison and Webster are correct, depending on the state and the activity in question.

State lands are a consequence of our national independence. In 1785, fresh from the Revolutionary War victory but prior to ratification of our federal constitution, a committee of founders fretted about how to parcel out the millions of acres of land in what was then known as the Northwest—primarily the Ohio River Valley and its tributaries. The Land Act defined how settlers could obtain this “vacant” land, establishing counties that were divided into 6-square-mile townships. Each township was further divided into square-mile sections, 36 per township. Each of these sections could be sold or granted to qualifying settlers, or kept in the public domain to be used for a defined public purpose. West of the Mississippi, it became common that two sections in each township, 16 and 36, were granted to the state as trust lands.

In almost every case, as these areas were settled and their statehood established, the public purpose of state sections became the establishment of public institutions, usually schools. This is another consequence of the visionary Land Act. Founders were sensitive to equity of new states entering the Union, and didn’t want these citizens carving homesteads out of the virgin forests to be at a disadvantage with the older, established colonies that became America’s first states. In what later came to be called the “equal-footing doctrine,” they settled on state trust lands as the mechanism to fund the public institutions that they hoped would perpetuate democracy in the fledgling nation.

Revenue from these state sections would be collected by state governments and used to build schoolhouses and county courthouses and to fund the creation and operation of public universities, which came to be called “land-grant colleges” in many Western states. In most states, then and now, revenue was generated by leasing the state lands to private citizens or corporations for a specific purpose. Sometimes it’s to be grazed by cattle. In other places, it’s to be mined for minerals or to be logged for timber. In almost all cases, then and now, other non-revenue-generating activities are secondary to the money-making purpose of these lands.

The Colorado Dilemma

Most states are satisfied with receiving sustainable funds from their trust lands. But others are keen to maximize the revenue, which can create some interesting tensions on the ground. Take Harrison’s home state of Colorado.

Colorado has so successfully maximized the revenue potential of state sections that it has raised $1.4 billion over the last 10 years for public schools. But it’s done that by creating a market-based lease arrangement for state lands that can be at odds with public access. Many hunting outfitters, Harrison included, lease state sections for more money than the state might make in a multiple-use scenario, and then exclude the public in order to increase the carrying capacity for big-game animals. The more valuable the state section, the higher the lease and the receipts that go to Colorado’s schools.

The onX/TRCP report focused on Colorado’s management, noting that only about 20 percent of its 2.8 million acres of state lands are open to and accessible by the public.

But Harrison says the arrangement has worked well. It’s poured money into public-school accounts, and it’s also benefitted the land.

“Of all the Western states, Colorado has stayed most true to the idea of what school trust lands were intended to do, which is generate income off recreational and agricultural use,” says Harrison. “The state allowed leasees to make improvements to the land, and the state rewarded those leasees with recreational access and the ability to recoup some of that investment through fees that the landowners could charge.”

But sportsmen and women in Colorado have balked at the system. Why, they ask, are they locked out of legally accessible state lands that are benefitting only a small number of private interests with a profit motive?

The question became so pointed that earlier this year, the state’s land board and wildlife commission agreed to use hunting and fishing license revenue to pay some of those state leases, opening nearly 500,000 acres to public recreation.

Harrison says the arrangement is unsustainable.

“They’re taking land from people who had the recreational rights, and they’re using state money to pay the state for something that the private leasee was previously paying,” he says. “That’s robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

A Changing Definition of Public Purpose

But Webster says the system is sustainable, and is copying what other states are already doing to secure public access to state trust lands.

“I’d characterize Colorado’s mechanism as evolving,” says Webster. “But it’s similar to the way that Montana, Washington, New Mexico, and Arizona secure public access.”

Those states attach a fee to hunting licenses, or ask recreationists to pay a state-land access fee directly, but in any case, the payment satisfies the revenue mandate of each state.

Will each of these small license surcharges equal the large sums that lease-holders pay for exclusive use of state sections? Over time, Webster says that they do, but he cites another benefit of allowing public access to state sections.

“There’s a growing awareness of the economic engine powered by outdoor recreational activities,” says Webster. “Not just hunting and fishing, but hiking, skiing, and mountain biking. All those activities return money to rural economies, and indirectly to state trust accounts. The more land available for these activities, the more revenue is generated.”

Besides, Webster points to language in Colorado’s constitution that charts a path to a broader public-trust requirement of state lands, beyond simply funding schools.

“In 1996, voters approved Amendment 16 to the Colorado Constitution, which significantly altered the terms of the state’s trust mandate to emphasize a mission of long-term stewardship rather than just revenue generation,” he says. “This stewardship principle required consideration of both economic values and other public values, including environmental, aesthetic, and recreational values. Rather than requiring the State Land Board to maximize revenues, the board is instead required to manage trust lands in order to produce ‘reasonable and consistent’ income over time.”

As further evidence of the evolution of the state-lands value, Webster noted that in Montana, which currently has one of the most recreation-friendly policies toward trust lands, sportsmen were locked out of state lands until hunters and anglers pushed the issue 30 years ago.

“I think states see the larger value of including all users and uses of state lands,” he says. “History is on our side here. This is an issue that sportsmen will win on going forward.”