Big trout are not necessarily genetic mutants–they’re simply voracious feeders that are constantly on the prowl for an easy meal, which means some of the slabbiest salmonids of the year are highly catchable right now in the tailraces below dams.

Whereas most of the year big fish sulk in deep holes and feed mostly at night, in winter the baddest brownies and most reckless rainbows head to the churning waters of dam outflows. These behemoth trout–particularly browns and rainbows–abandon their usual cautious ways to get in on the food buffet and chow down on churned-up bait pieces spit out by dam turbines.

“It has been my experience that tailwater fish act much different from regular [river] fish,” says big-trout fanatic Kelly Galloup, author of Modern Streamers for Trophy Trout and owner of the Slide Inn on Montana’s Madison River. “First, you have the filter feeders that sit and eat Mysis shrimp all day. Then you have the fish that basically take up residence below the dams, becoming free-foraging meat-eaters. Here on the Madison in Montana, I have that situation. The fish are generally taken with bigger diving crankbaits and mostly at night. They seem to look primarily for really big food sources, such as chubs, crayfish, and medium (6- to 12-inch) trout. Targeting these fish can be difficult simply due to the volume of water that dams can put out. The unique situations are when you get a push of stunned fish. Obviously when that occurs, the forage base is right in your face, so you simply match the food with an appropriate-size fly or lure. I have seen where killed or stunned cisco and shad (not all the fish are killed; many are simply stunned and have trouble regaining equilibrium) can go for miles below the actual dam. In my experience, this is the ultimate in feeding frenzies for truly huge fish.”

Galloup’s obsession is hunting the biggest browns of the year. “I can’t explain the addiction. It’s primal. There’s something savage about the way big browns look–and it’s so rare to catch a 10-pound-plus brown. It’s special. It’s like trophy hunting.”

Top Tails

In expansive tailwaters, where the water is cold and usually holds lots of whole or chewed-up bait, try trolling. One of the top tailwaters in New England, for example, is the Connecticut River below Moore Dam, north of Littleton, N.H. Porker browns in the 10-pound-plus class–with the large spots and custard-color bellies–regularly come from this New Hamphire-Vermont border water. The Moore’s sister dam, the Comerford on the Connecticut River, is also a big-brown place of local lore. The Western tailwaters like the Madison, Yellowstone, and South Fork of the Snake, and the White River in Arkansas, where Dave Whitlock has perfected many of his big-brown fly patterns, are prime sites to find trophy brown banquets each winter.

The tailwater section of the White River runs more than 90 miles from Bull Shoals, thanks to a cold-water infusion, back into the White at the confluence with the Norfork River. This section is brown-trout central. Guide Donald Cranor, of Gassville, Ark. (troutguide@gassville.com), looks for gravel-bed spawning areas (redds), and drifts egg patterns or salmon-egg sacs off the redds for 7- to 9-plus-pound browns.

“Another very effective method is to back-troll stickbaits like a Smithwick Rogue or Xcalibur XEE4 EEratic Shad. Just hold your boat in the current and cast downstream, letting the current do the work,” says Cranor. “If you don’t get a strike, let the boat drift back a few feet and try again. A 4 ½-inch bait darting around a spawning redd is enough to get the attention of big browns. Of course, this all depends on the amount of water that is in the river at the time. Your bait has to be close to the bottom for this to work.” That’s a good point–remember you’re fishing tailraces, so the water level will fluctuate due to dam releases.

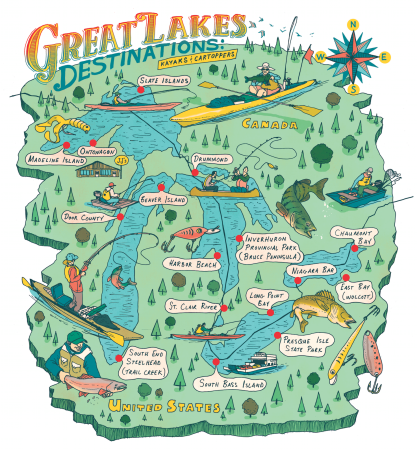

Lake Ontario tributaries such as the Salmon River in mid-northern New York are revitalized for anglers with surging runs of steelhead and salmon each winter. But the big attraction these days are the truly outsize brown trout–the super-slobs–that follow the steelies and Pacific transplants, scarfing down the egg clusters of these spawning fish. Any brown approaching 10 pounds earns a slob nod. But consider that the New York State-record brown of 33 pounds 2 ounces came from Lake Ontario. Or that a former world-record brown of more than 41 pounds came from Michigan’s Manistee River. In the Great Lakes’ dam-area outflows, trolling deep-running crankbaits (that New York record took a Smithwick Rouge) is a primary method, and tailraces are a trophy-worthy place to center your efforts.