I have never caught a muskie on the fly. Not in Minnesota or New York. Not in Pennsylvania or New Jersey. I tried in Washington State once too. In every location I’ve had looks and follows. I’ve had muskies trail my fly so close that the tail feathers were tickling their nostrils. Never has one opened its mouth to eat, yet the sore shoulders and arms eat away at me regardless. When you’re flyfishing for muskies, you can’t help but feel a little nuts. The method doesn’t let you cover water like you can with conventional gear. You can’t make a fly kick, spin, and vibrate quite like the lures these fish often crush. In many fishing scenarios, a fly rod is a better tool for the job, but this isn’t one of them.

You flyfish for muskies because you believe it is the ultimate challenge. I certainly feel that way, but I also accept that I’ve failed because I’m not utterly devoted to the goal. I give it a go once or twice a year, which might eventually get the job done if I’m lucky. If you really want to succeed badly enough, it needs to consume you. Per social media, this game is consuming more people than it ever has before. It’s gotten trendy, yet behind every trend there are pioneers that were honing the craft long before the craft got cool. For every muskie fly-dabbler, there are the guys who are singularly focused on this challenge every time they get out to fish. I’ve tracked down four of them. Some have been at it since the early ’90s, experimenting with tactics in a time when there was almost no information to feed off. Others have fewer years of experience, though more time on the water and muskies to their credit than guys like me ever will. They all bring a unique perspective to critical parts of muskie fly success, yet they all share the same addiction to getting a fly-hooked fish in the net and the agony of being haunted by beasts that showed themselves without chewing. If you’re thinking about joining their ranks, their insights and a look at what makes them tick will get you primed for the madness.

On Rivers: The Whitewater Sage

“There are days when I wake up and say, ‘Boy, I don’t know about this,’” Brad Bohen admits. “Hanging a shingle out as a muskie guide is one thing, but keeping the lights on is another.” Still, in 15 years of guiding flyfishermen, Bohen has never once thought of giving it up. He may seek other avenues of income, most recently launching a fly-material company specializing in top-quality, hand-dyed bucktails. Getting off the water, however, will never be an option. As Bohen puts it, when you grow up in Wisconsin, muskie fishing is part of your DNA, and he’s often credited with engineering new mutations within that DNA. He’s been tinkering with patterns and techniques for these fish since long before many new-school fly guys ever thought of giving them a go. But for those trying to follow in Bohen’s footsteps, the best flies and abilities won’t mean much if you’re not on the right water. Bohen knows his way around lakes, but he’s considered a river muskie specialist, and he believes success comes faster on a river when you understand how muskies behave in moving water.

“A lot of people think muskies are lazy,” he says. “They’re not. They’re very athletic fish. They’re streamlined. They can jump waterfalls. I catch a lot of them in rapids, and they can handle the chaos of heavy water very well. ”

In many regards, reading a muskie river is like reading a trout stream; holes, seams, and structure such as laydowns and rocks that break the current have the potential to hold these fish. Bohen hits all of that obvious juicy stuff, but his discovery of fish in fast water stemmed from his desire to seek out less-pressured targets. The average muskie guy—whether on a drift boat or jet boat—will pass up or avoid heavy, boulder-strewn water altogether, leaving the door wide open for Bohen. He’s so successful in heavy water that he cites it as a key characteristic of a great muskie river. But even more important, Bohen wants diversity and as natural a river as he can find.

“I think of muskies as being like brook trout,” he says. “The purer the ecosystem, the better they thrive. People with property along a lot of Midwest rivers mow their lawns right down to the water. They remove trees and brush. I don’t really like fishing in rivers in heavily populated areas, which is why I moved to northern Wisconsin.”

Bohen operates a muskie camp near Winter, Wisconsin, on the Flambeau River, which he considers the finest moving muskie water in the country. A stay at one of his cabins is specifically designed to make you connect with nothing but muskies and friends. There is no cell service. There is no wi-fi. This stretch of the Flambeau takes you back to an era when early fly pioneers from the ’20s and ’30s were catching these fish on huge bucktail flies with absolutely no fanfare. Bohen soaks up rare tidbits about these old-timers like a sponge, scouring dusty lodge logbooks and scribblings on ancient photos. Considering that the section of the Flambeau where Bohen operates remains about as wild as it was a century ago, it also fulfills another essential criterion: food diversity.

“A balanced ecosystem isn’t just about water,” Bohen says. “Muskies eat fish and crustaceans, of course, but they’re also going to go after mammals, amphibians, and birds. An abundance and diversity of those things is important. I love topwater fishing, and when the baby ducks are on the water? Yeah, you’d better believe those fish are looking up.”

On Lakes: The Record Holder

Absolutely nothing had happened for four hours on November 9, 2015. Robert Hawkins will admit that casting and stripping heavy gear, looking at scenery that never changes, and hoping your fly gets in front of a muskie on giant Lake Mille Lacs in Minnesota is painfully monotonous. It’s very easy to lose focus. Luckily, even after those uneventful four hours, his eyes were still glued to his fly.

“There were three of us on the boat, but I’m the only one who saw it,” Hawkins recalls. “All of a sudden, it just looked like the open end of a white 5-gallon bucket behind my fly.”

The fight lasted less than a minute, but the notoriety that came with landing a 57-inch muskie estimated to weigh more than 50 pounds will stay with Hawkins forever. He says at first he was too scared to go look at the fish in the net. The Freshwater Fishing Hall of Fame certified it as the largest muskie ever caught on fly, and although Hawkins had only been chasing these fish for a few years, he was fast-tracked to expert status in the muskie fly scene. He’ll be the first to tell you he’s still got much to learn. But ever since he nailed the record, he’s been learning a lot about still-water muskies.

“In rivers, the spots where you’re going to find muskies are a lot more obvious than they are on a lake,” says Hawkins, who moved to Minnesota from Montana in 2013 to take over Bob Mitchell’s Fly Shop. “Not that they’re easy to catch in a river, but they’re a lot more predictable. I’ve fished rivers my entire life, so lakes are a new challenge for me. I’m also a technology geek of sorts. I want all the cool new electronics.”

Hawkins certainly didn’t start out by leaning on side-scan and lake-mapping software. His first stabs at muskies on the fly were taken blindly, walking around local Twin Cities lakes and hoping. According to Hawkins, the average angler coming into his shop for advice is doing the same thing, though these days he tells them that putting even the inexpensive Navionics app on their phone can increase their chance of success tremendously. A picture of a lake’s contours, regardless of its size, is invaluable to help you at least figure out where the holes, drop-offs, and reefs these fish frequent are located. Having that intel is a confidence booster, and Hawkins says you need all the confidence you can get when fishing lakes, because the muskies are generally much harder to catch.

“Lake fish are a lot less opportunistic because they can sit in one place and let food come to them,” he says. “In a river, they kind of have to hunt their food. They have to make quicker decisions. A key thing I’ve learned on lakes is that you’ve got to move your fly fast.”

Hawkins has a theory that conventional gear anglers are much more successful on lakes because of the sound signatures lures like bucktails and swimbaits produce. You can tie flies with a wide head that will push water, but mimicking that high-speed vibration is no easy feat.

“You catch a lot more muskies in the figure eight on a lake,” says Hawkins. “They’ll follow from a distance, but it’s hard to strip that fly as quickly as you can swirl it with the rod tip right by the boat.”

On Technique: The Young Gunner

It’s the gill flare that Luke Swanson remembers most. He was 12 years old, fishing with his dad and grandfather, when the 47-inch muskie inhaled his live sucker. Having already learned how to fly-fish, it was at that moment Swanson knew that seeing that gill flare behind a streamer was something he needed. By 15, he had landed a few muskies that broke 30 inches. By 17, Swanson says, everything started to click, from patterning to presentation. The funny thing is, this wasn’t very long ago. Swanson is only 22, though the young gun’s reputation as a muskie fly guide on the Mississippi in his home state of Minnesota is flourishing. He’s already put lots of anglers on their first muskie, and even led renowned author John Gierach to his biggest.

“It took me seven years to top that 47,” Swanson says. “But even today, I don’t like to fish topwater flies because I love to see that gill flare below the surface.”

Swanson spent a season guiding in Alaska when he was 18, and although he loved it, he missed muskies and smallmouths too much. These days, he’s running well over 100 guide trips per season, more than half of which are devoted to muskies. Of those trips, in 2018, Swanson says he blanked maybe 10 times. That’s impressive, considering not all of his clients are fluent in the techniques required to catch these fish.

“You never want the fly to have the same cadence,” Swanson says. “You’re not trying to walk the dog. Every retrieve should be erratic, and you need to constantly change strip speed, pause length, and the number of pauses. Erratic action is what’s going to trigger muskies most of the time.”

Getting interest—and hopefully a take—is only the first part of the battle. The real technique kicks in after that chomp. Nothing costs more fly muskies than the dreaded “trout set.” Lift the rod to strike, and the fish is gone. Strip-striking low and hard is imperative for drilling fly hooks into a muskie’s rock-solid mouth. According to Swanson, many of his clients have trout flyfishing or conventional fishing backgrounds, making that need to strip-strike tough to remember in the split second when it counts. It’s equally critical to have minimal line off the rod tip during a figure eight to help get a positive set if a muskie eats close. Swanson prefers 15 inches, noting that if you’ve got a hot fish swirling next to the boat, it doesn’t care about your rod tip. It’s not going to spook.

Even if you do get a muskie pinned, you still haven’t won. Swanson says many anglers want to raise the rod to fight, which can be almost as damning as trout-setting. “I always tell people, you never want the rod at eye level,” he says. “It should be low and to the side, bent as hard as you can bend it throughout the fight.” The need to keep up the heat is one reason why Swanson uses two-handed fly rods made from medium-heavy conventional rod blanks. The other is to save your shoulder. “I tie on an 18-inch fly, and using that rod, you can cast it for two days straight and not be sore.”

On Flies: The Lion Tamer

Blane Chocklett likens muskies to lions. They’re social creatures. They “sleep” together, and when they decide they want to eat, they go kill something, come back, and “sleep” again until the next feed. It’s this behavior that makes them so hard to catch. Not only does your fly have to be in front of a fish that wants to feed, it has to make that fish decide your fly will be the only meal it might get for days. Chocklett calls the New River in Virginia his home waters, and he’s been fishing it since he was a kid. In the early ’90s—at a time when, he says, nobody was muskie fishing the New—a teen Chocklett drew inspiration from Larry Dahlberg, who had been throwing flies at muskies for decades. Today, Chocklett is an authority on fly-tying, and he says the productivity of modern flies blows away the patterns he grew up learning on.

“These days we have a lot more eats out from the boat than we did years ago,” he says. “That tells me our flies are creating the right triggers, and a fish that eats out is easier to catch than one you don’t see until it’s next to the boat.”

In the muskie genre, Chocklett’s jointed T-Bone Fly is his masterwork. Its key feature is its ability to turn sideways on the pause, exposing its full profile to the fish. It’s also tied with a reversed bucktail to give the illusion of mass without adding weight.

“You want to have a large head on any muskie fly,” Chocklett says. “It’s like creating a dam that diverts water around the head. On the strip, that head stalls, but the rest of the fly keeps going, so it jackknifes. Most of the fish I catch T-bone the fly when it shows its profile. They just drive right through it, man.”

Chocklett says it’s also essential that a fly has the ability to turn and show off that profile at a variety of retrieve speeds. In spring especially, Chocklett often employs a fast, double-hand retrieve to really get a fly moving. He says muskies generally are more apt to chase when the water is cooler. Constantly changing retrieves is imperative because you can’t catch a muskie you can’t make move.

“It’s like a cat with a laser pointer,” Chocklett says. “Once you get him engaged, you can start teasing him and get him. But the whole game is about just getting to that point.”

Read Next: 5 Pros Share Their Topwater Muskie Fishing Secrets

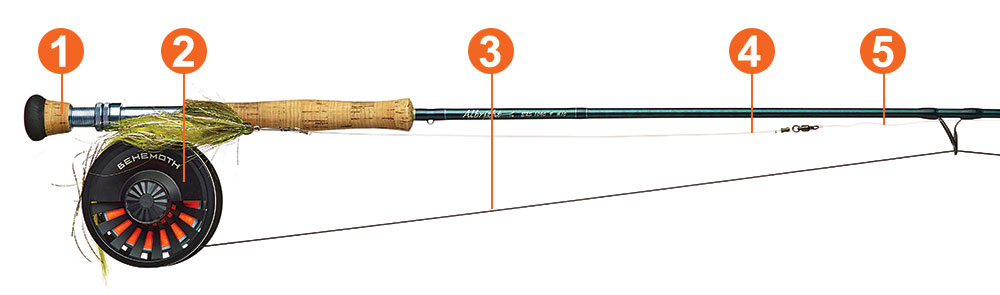

1. The Rod: At minimum you’ll want a 10-weight rod, though many muskie nuts lean on 12-weights. Make sure it’s a good caster for delivering those meaty flies. But more critically, make sure it has the strength and backbone to drive hooks and muscle fish to the net without snapping.

2. The Reel: Most muskie fights will be short and very sweet, and will happen pretty close to the boat, so you don’t need a drag that can stop a tuna. A reel with a midrange price tag that’s the appropriate size for the line and rod will suffice.

3. The Line: To help get bulky muskie flies down and keep them there, you want a sinking line. A slower intermediate sinker will get you by in most scenarios, but having a 250- or 300-grain sinking line will come in handy in deeper water.

4. The Bite Tippet: Whether connected by crimps, knots, or a barrel swivel, the bite tippet material is often a topic of debate. Some anglers lean on light steel cable. Others like single-strand steel wire. I’ve talked to many, however, who prefer 80- to 130-pound fluorocarbon, because they swear its low visibility increases strikes.

5. The Leader: Many muskie fanatics skip tapered leaders, believing sinking lines and heavy flies provide plenty of turnover juice. Four or 5 feet of 40- to 60-pound fluorocarbon is the norm.