After posting his “manifesto” on Facebook outlining plans for a revenge-fueled murder spree targeted at law enforcement officers, Christopher Dorner had been a fugitive in the California’s San Bernardino National Forest for nearly a week. He had already killed three people, and he would add one more murder to that tally before his reign of terror came to an end.

On February 12, Dorner was spotted by law enforcement officers as he drove a stolen car behind a pair of school buses on State Route 38. The officers lost track of that vehicle, but they didn’t lose track of Dorner. Knowing the mountain roads well, they found him again as he passed them in yet another stolen vehicle, this one a white pickup.

When Dorner saw the officers, he opened fire spraying bullets through the front windshield and driver’s door window. Several bullets pierced the vehicle’s cabin, including one that lodged in a seat just 10 inches from the driver’s head.

The officers returned fire, sending about two-dozen rounds into Dorner’s vehicle. Dorner eventually crashed the truck into a snow bank and fled to a nearby cabin. A short time later, the cabin was ablaze and Dorner was dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Dorner (pictured, left) was a former Los Angeles Police Department officer and had received extensive training at the department’s academy (he also received training as a Navy reservist). The officers responsible for finding him had received the same type of training. But, they had an extra edge that likely gave them the advantage in the California mountains: They were game wardens.

The highly publicized shootout serves as just one more example of an inescapable fact facing game wardens across the country: their job is evolving–and getting more dangerous all the time.

Superior Firepower

Patrick Foy, a Lieutenant with the California Department of Fish and Game, says he’s seen substantial changes in the types of crimes conservation law enforcement officers in his state now face.

“The criminal element is far more dangerous now than it ever was,” he says. “The proliferation of methamphetamine, the large-scale growing of marijuana in our National Forests, those things have really changed the landscape for us as wardens.”

The majority of people that game wardens encounter are armed, and statistics from the National Association of Conservation Law Enforcement Chiefs show that a game warden is seven times more likely to be assaulted with a deadly weapon than any other law enforcement officer. These encounters often take place in rural areas miles away from backup.

Since 2005, California game wardens have been involved in eight shootings (there is no available data on the number of shootings involving wardens nationally).

To meet the growing responsibility and increasing threats, many game and fish departments are beefing up their crime-fighting equipment and changing their tactics.

Foy says CDFG underwent a facelift about eight years ago at the urging of recently-retired Chief Nancy Foley. Prior to Foley’s tenure, CDFG wardens attempted to “live in the shadows.” The intent was to catch fish and game violators with stealth. But as more violent crimes were committed in the rural areas that wardens commonly patrol, it became clear that more aggressive tactics were needed.

“We came out of the shadows. We changed the way we mark our vehicles to make them more visible, we changed our uniforms, our procedures and training,” Foy says. “And, just as importantly, [Foley] made sure we were better equipped for the work that we do.”

The equipment upgrades included better protective gear and more firepower. California wardens are now issued two pistols, a shotgun, and a semi-automatic rifle.

“It was that type of rifle that was used in the confrontation with Christopher Dorner,” says Foy. “When a high-profile crime is committed in a rural area, we do feel that it’s highly likely that a warden will somehow be involved in that case. We just have a very good understanding and knowledge of those areas and we’re able to pick out things that just seem out of place. That’s what happened in the Dorner case.”

On a National Scale

“When I first saw the reports that Dorner was likely hiding in the mountains, I told my wife, ‘Wardens will have something to do with catching him,'” says Randy Stark, Chief Warden with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources’ Bureau of Law Enforcement. “She asked me why I thought that, and I said, ‘Because, they know those mountains better than anyone. If he’s there, they’ll find him.'”

“We’ve always been sort of a dual-purpose officer,” says Stark, who is also the President of the National Association of Conservation Law Enforcement Chiefs. “We’ve always taken on traditional law enforcement duties from time to time… But things really changed after 9/11. That event sparked a real focus on law enforcement as a community effort.”

Stark has been in conservation law enforcement for more than three decades. He joined Wisconsin’s warden service in 1984, becoming chief in 2002. In that time, he’s seen plenty of bad guys stopped by game wardens. He’s also seen the role of the game warden change dramatically.

Stark says today’s wardens learn basic law enforcement training and highly-specialized skills that make them well-suited for enforcing fish and game laws and assisting in enforcement issues outside city limits.

“We’ve got access to equipment that’s ideally suited for use in rural and water environments. And we’ve got the training and skills to use them,” he says. “We have ATVs and boats of all shapes and sizes. We have officers trained to use them. Game wardens, really, are ideally suited to handle law enforcement issues that occur in places traditional law enforcement probably isn’t equipped for.”

The good old days of a game warden driving around and just checking licenses seem to be over. In 2010 a Pennsylvania game warden was killed in a shootout with a deer poacher while patrolling rural roads at night. The state police commissioner described the shooting as “a ferocious exchange of gunfire.” The poacher was eventually captured and convicted. In Texas, game wardens help patrol the U.S./Mexico border, and a group of wardens were involved in a gunfight there with Mexican drug runners during the summer of 2011. Stark cites an even more violent incident in Wisconsin as the reason for the WDNR’s shift in equipment and tactics.

“Our officers used to just be issued shotguns. Now we issue rifles and shotguns,” says Stark. “This was a result of an incident in which we had someone shoot and kill six hunters. We had to go in and find him and, at the time, we only had [Remington] 870 shotguns. We were badly outgunned. All of our wardens now have tactical shotgun and rifle training. All of our wardens also now go through active shooter training. Like every other area of law enforcement, we have to be aware of the times we live in.”

**

A New Breed**

Mark Michilizzi is on the opposite end of the experience spectrum from Stark. As Stark prepares to retire in the fall, Michilizzi, who has been a warden with the California Fish and Game Department for just three years, is only getting started. In many ways, Michilizzi is a living representation of the evolution of the game warden that Stark described.

To become a warden, Michilizzi had to attend the same training academies as California police officers, in addition to special training required to patrol wilderness areas and enforce conservation law.

The fact that game wardens will likely be outnumbered and outgunned is stressed in the training process. It also forces them to use a different approach than other branches of law enforcement employ.

Stark, in fact, said that it’s a game warden’s ability to communicate that makes him uniquely qualified to handle difficult situations in remote areas.

“If you encounter a situation in the woods, you’d better be able to communicate effectively. You can’t just run in there with your hand on your gun and say something that’s going to escalate the situation,” he says. “You have to use your communication skills as a method of defusing that situation.”

Perhaps the most underestimated challenge for the modern-day game warden is changing public perception about the job.

“I don’t think people really understand what game wardens do. They assume we only focus on fish and game laws and natural resource protection,” says Michilizzi. “And that’s certainly a priority. But public safety is our top priority. You have those times where you make contact with a father whose son has just killed his first deer and that’s an incredible experience to share. But right over the hill might be someone growing marijuana, and he’s got a bunch of buddies with him and they’ve got guns and aren’t happy to see you.”

_Photo Captions (from top):

– Texas game warden Jake Mort travels with an M-16 on a Parks and Wildlife boat as a U.S. Coast Guard boat is seen in the background, on Falcon Lake, which straddles the U.S. Mexico border in Zapata, Texas (AP Photo/Eric Gay, File).

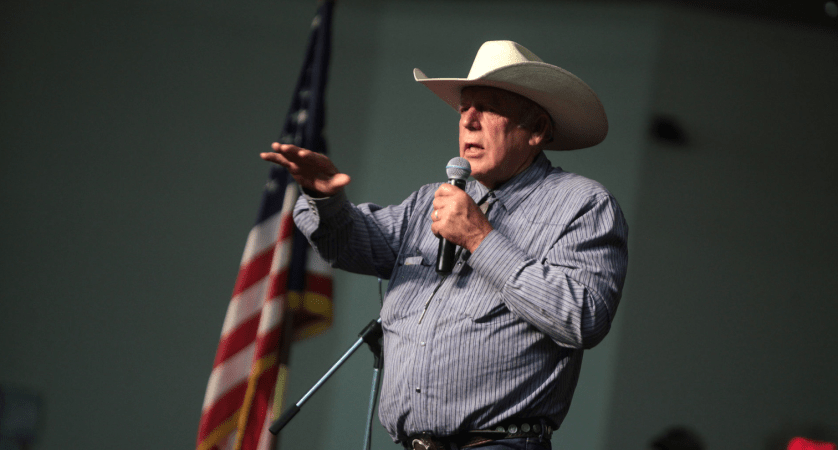

– Christopher Dorner, an ex-LAPD police officer and U.S. Navy reservist. Dorner was deployed to Bahrain with Coastal Riverine Group Two in 2006. He was honorably discharged from the Navy Reserve on February 1, 2013.

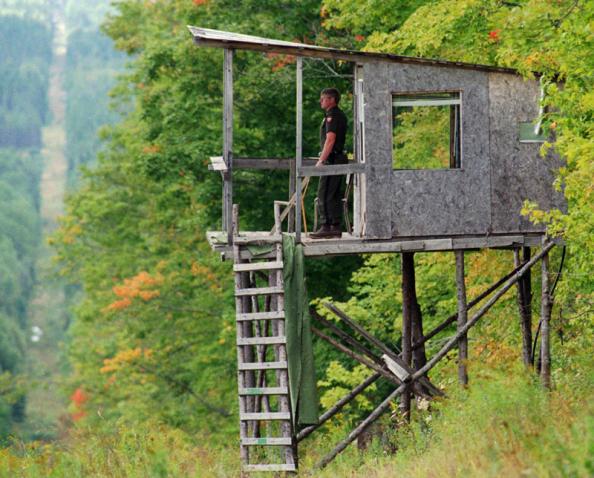

– Sgt. David Allen, a Maine game warden, checks the view from a Canadian hunter’s unoccupied “cache” along the Quebec border. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)_