Sea water is rising in tidal areas from the Carolinas down to the Florida coast, and that could be disastrous for aquatic grasses and the inshore fisheries they support. In North Carolina the changes in water, grass beds, and coastal aquatic life have been dramatic, according to a report from Carolina Public Press.

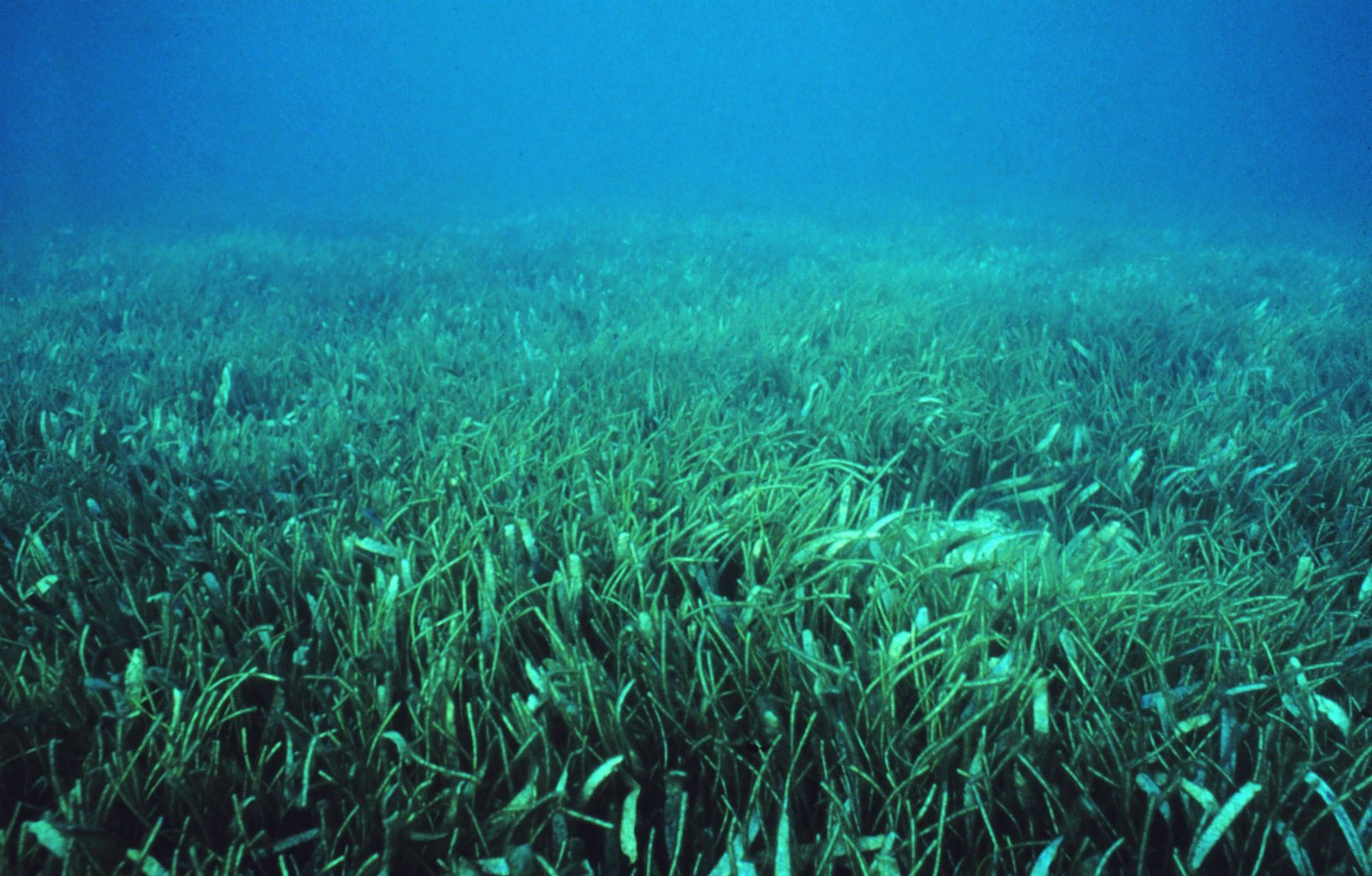

North Carolina has about 120,000 acres of seagrass habitat tucked around barrier islands and in estuaries along the coast. A unique mixing of seawater, brackish water and freshwater (in the lower reaches of coastal rivers) creates a rich nursery grass haven for a variety of species that allows year-round aquatic abundance in many regions. The seagrass supports baitfish species like pinfish which are prey for groupers, snappers and dolphin. Popular inshore gamefish like redfish and sea trout also rely on seagrasses. Unfortunately for the fish, and anglers, seagrasses are declining all around the Carolinas.

“Nowhere are we seeing increases in seagrasses in North Carolina,” retired NOAA scientist Jud Kenworthy told Carolina Public Press. “And one thing is clear, if you don’t have seagrass, you’re going to lose fisheries. That’s unacceptable.”

Saltwater flowing in and out of costal marshes fosters a staggering amount of diversity, providing food, refuge and nursery habitat for more than 75 percent of fisheries species, including shrimp, blue crabs, and finfish, reports Carolina Public Press.

READ NEXT: Florida’s Water Crisis Has Sport Fishing on the Brink of Collapse

“Seagrass and marshes are dynamically interacting with each other,” Kenworthy, an adjunct faculty member at UNC Wilmington, told the Public Press. “Many (aquatic) species need both, and we are just now beginning to insert a way of thinking into this process at larger scales and time frames.

As sea levels rise costal marshes are flooded with more salt water, which throws off the balance of a delicate system (certain plants cannot survive being constantly submerged).

“Seagrass sets the stage for everything. Losing it threatens the entire system. It’s the driver of our fisheries. That alone justifies its protection.”

Carolyn Currin is a research scientist at NOAA’s laboratory in Beaufort, North Carolina, studying microscopic organisms that flourish in marshes and seagrasses that form the basis of a vast food chain.

“Water (from higher sea levels) is inundating the lower and upper elevations of marsh for a longer time,” Currin said. “So, the whole community of marsh has to respond to increasing periods of flood (tide).”

Higher water from rising tides increases salinity, diminishes sunlight needed by vegetation and reduces dissolved oxygen in the water. None of this is good for sustaining healthy coastal grasses and the aquatic species they harbor.

“Those marshes will not be fish habitat if they are underwater most of the time,” says Currin. “We really need to think about the future and come up with habitat restoration plans that will be resilient to an extra 6 inches to a foot of sea in the next 25 to 30 years.

“We’re thinking that those low marshes won’t be around in 10 to 20 years.”