A local conservation group and the U.S. Forest Service have proposed a land exchange that would put an end to decades of confusion over where the public can access the Custer-Gallatin National Forest in Montana’s Crazy Mountains. If the deal goes through, a new 22-mile public trail will wind through the eastern side of the Crazies, about 40 miles northeast of Bozeman.

The issue? Hunters say they will lose access to the public lowlands—and the elk that reside there—on the east side of the range. Now that the USFS is calling for public comment, which is open through Dec. 23, hunters are making their opinions known.

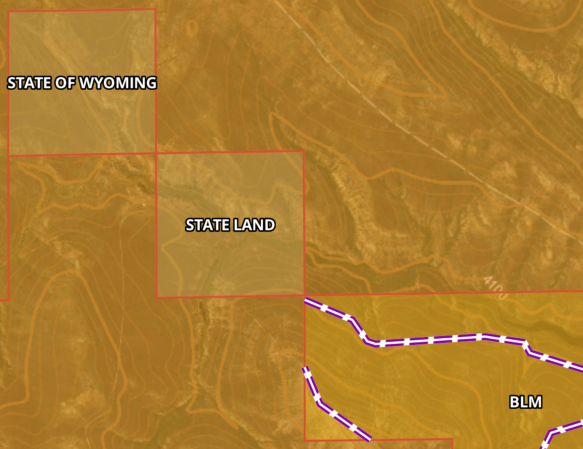

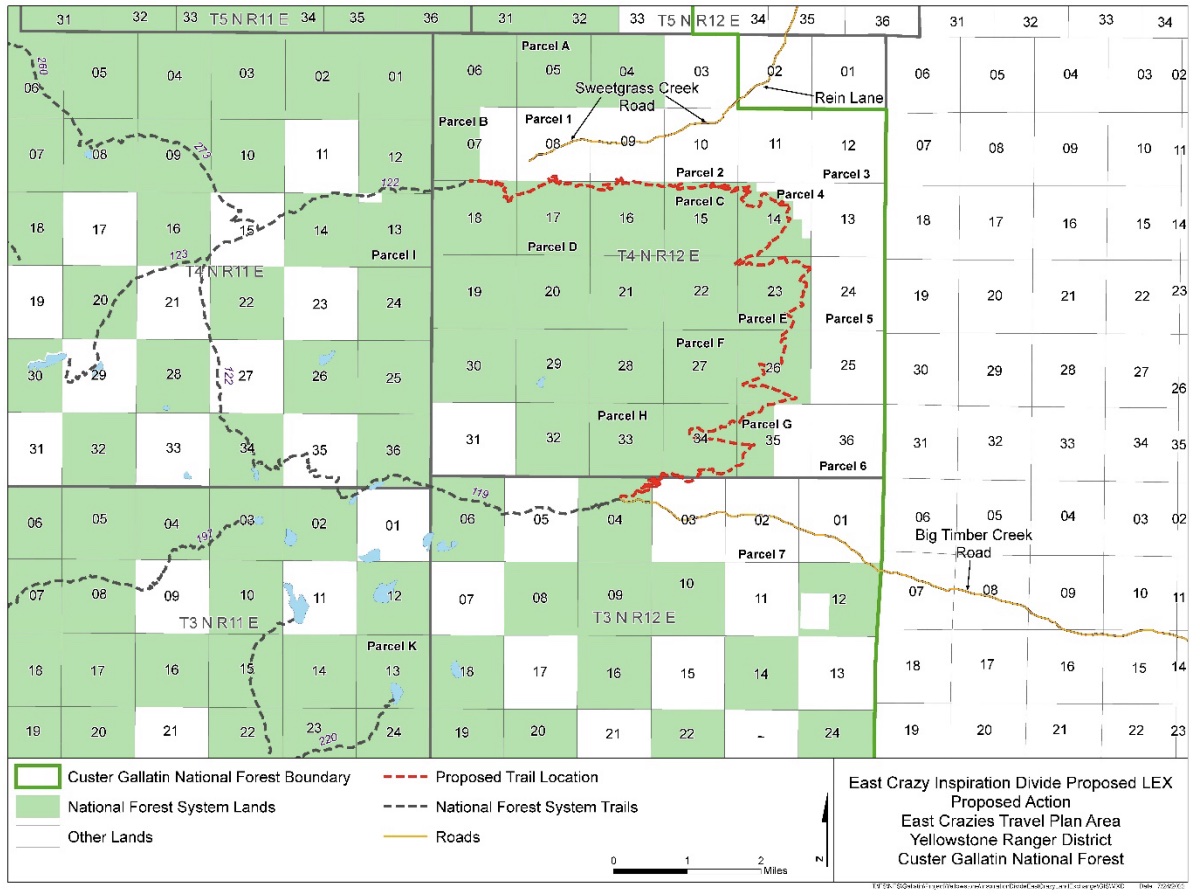

The swap was proposed by the Crazy Mountain Access Project, a group of ranchers, environmentalists, Bozeman and Livingston business owners, a representative of the Crow tribe, and members of the Yellowstone Club. The spirit of the deal is meant to secure public access to a checkerboarded landscape. Currently, access to the east side of the Crazy Mountains relies on prescriptive easement trails that cross private property in some places, which landowners have been obstructing and posting “No Trespassing” signs on for decades. The swap would consolidate the currently fractured public and private parcels through a series of land trades between six area landowners, the Yellowstone Club, and the Forest Service. It would then replace the historic East Trunk and Sweet Grass trails with a new 22-mile trail that would run through the consolidated public area. This would ultimately create a 40-mile loop trail through the Crazies’ impressive peaks.

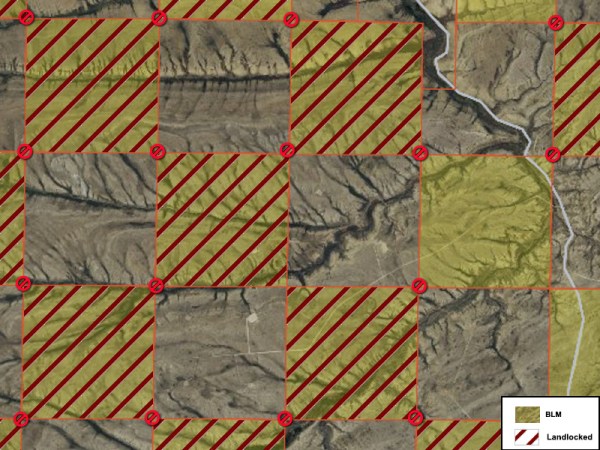

But the parcels that hold most of the area’s elk and deer could end up in private hands. In return, the public will get high-mountain country that many hunters consider unfeasible for scouting, hunting, and packing out meat without a string of mules or an endurance athlete’s physique. According to onX’s topography map, the eastern public land boundary will hardly drop below 7,400 feet, and the rare places where it does drop lower will bump against private land.

Many hunters wonder if the swap is even necessary in the first place. But those who are intrigued by the premise of consolidating public lands in the Crazies call this trade a bad one.

The Argument Against the Swap

As the proposal currently stands, six landowners would get 4,135 acres across 10 parcels and the public would get 6,430 acres across 11. But according to John Sullivan, chair of the Montana chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, the math doesn’t paint an accurate picture of how this trade impacts the public.

“In every metric in this land swap, the landowners win more than the public does, except for the actual acres being swapped,” Sullivan tells Outdoor Life. “The landowners get more stream miles, more water rights, and significantly more wetlands.”

Instead of a traditional land sale where a piece of land is appraised and issued a price tag, this swap operates under the premise that the traded parcels are equal in value. According to the proposal, if a final appraisal finds that the parcels aren’t of equal value, cash or other land might get added to the deal to make up for the inequity. But as far as hunting access and proximity to big game goes, Sullivan says hunters will lose no matter what.

“It’s very clear that we’re giving away the quality elk habitat in exchange for higher country and less productive landscapes,” he says. “The public will be congested on one trail into that particular landscape and the majority of elk reside on the lower country and in the Sweet Grass Canyon area.”

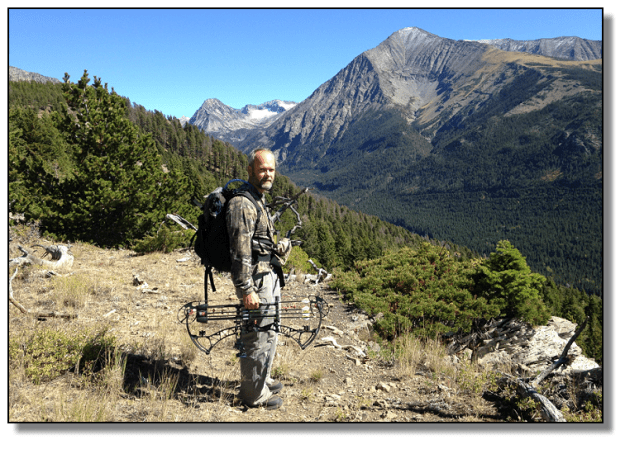

The consequences of a long, singular access point are already visible elsewhere in the mountain range. In October, Jake Lunsford drove to the Crazy Mountains from Rhode Island to hunt elk on public land with his brother-in-law, friend, and their young sons. They used the Big Elk Creek trail across private land on the McFarland White Ranch in the north Crazies, which the Forest Service secured an easement for in September 2020. The group hiked four miles to a Forest Service campground. When they arrived, they were met by eight other parties with mule trains.

Lunsford’s crew rode out some nasty weather for a week and eventually harvested a mature bull. But the elk dropped into a drainage close to a private parcel before expiring. As Lunsford and his 7-year-old son quartered the bull, a string of pickup trucks pulled up and parked on adjacent private land. A large group of men proceeded to stare at Lunsford and his son through binoculars while they broke down their elk. Then the Marine Corps veteran began his six-plus-mile packout.

“Hunting is not purely hiking, and at some point you know a big load is going on your back, and that if you don’t get the meat out in time you have sinned against God and elk alike,” Lunsford says. “I am grateful to the landowner and the Forest Service [for] granting me a way to access lands that we all own. But…if access is so far from the elk that I can’t physically retrieve my quarry on a successful hunt, is it really access?”

The swap could be a bad omen for public land hunters across Montana, says Andrew Posewitz, a Montana historian, conservation advocate, and founder of the Montana Public Trust Coalition.

“This is a terrible proposal for hunters. It will effectively turn [hunting in] the Crazies into a one-shot season,” Posewitz says. “After opening weekend, the elk will concentrate on the newly private low country where there is less snow and less pressure.”

To Posewitz, BHA, and other organizations decrying the swap, this all started with the Forest Service not defending the historic prescriptive easements on the Sweet Grass and East Trunk trails. They fear the saga is going to end with those trails—and prescriptive easements everywhere—facing erasure and abandonment at the hands of landowners who get away with blocking public access.

“The Forest Service has failed the public and they know it. They know they botched these prescriptive easements. Their written record universally asserts the public’s right up these trails, but they have subsequently abandoned them, and they’re trying to hide that fact with this land swap,” Posewitz says. “It is the equivalent of burning down the building to cover the body they shot.”

The Argument for the Swap

The exchange is an easy sell for lots of interested stakeholders. Hikers and trail runners get access to that special high-mountain scenery that the Crazies are known for. Mountain bikers get thrilling elevation change. Everyone can comfortably leave the trail knowing they aren’t in the proverbial crosshairs of a wary landowner, and landowners won’t need to worry about the public crossing their lands. Those who run outfitting services will have access to even more elk on the lowland parcels they’re gaining.

“Re-routing the East Trunk trail to consolidated public land is a better solution in terms of clarity for the public,” CMAP member and Park County Environmental Council deputy director Erica Lighthiser says. “[The public would be able to] access public lands and walk or ride on a trail that is clear, easy to follow, identifiable on the landscape, and also resolves this long-standing issue. The previous, historic route on the east side went through a lot of private land.”

The Crow tribe will supposedly get access to Crazy Peak, a place of cultural significance where members have fasted, prayed, and visited since time immemorial. The Crazy Mountains were originally part of Crow tribal lands before colonialist settlers arrived and drove them from the range in the 1860s. In the swap, Crazy Peak will remain in the hands of David Leuschen, former partner at Goldman Sachs, co-founder of a private equity firm in the energy sector, and owner of Switchback Ranch. As the proposal says, Leuschen would sign an agreement with the tribe allowing members exclusive access to Crazy Peak, which he would put in a conservation easement to prevent any future development. (Opponents of the exchange point out that any binding contract holding Leuschen to this agreement is absent from the proposal.)

Leuschen is a member of the Yellowstone Club, the group that provides financial backing for CMAP and would pay for the trail reroute. As of 2018, the exclusive community in Big Sky, Montana charged a $400,000 deposit plus a base annual fee of $41,500 for all members. That’s before the multi-million-dollar condos and private ranches and the five-figure homeowner’s association fees.

The Club’s interest in this proposal lies in a different part of the trade. They would add 500 acres near Eglise Peak in Big Sky to their expert ski terrain. In return, the public would gain 558 acres adjacent to the Inspiration Divide trail, much of which is steep and about half of which is above the tree line. In fact, between those two parcels, the public gets the highest piece of snow-choked ground: over 9,700 feet above sea level on the eastern slope of Cedar Mountain.

Some hunters are on board with the swap for the sake of consolidated public lands and clarity on where they can legally access them. The long trail would also limit hunting pressure by weeding out those who don’t have what it takes—either the cardiovascular strength or the stock—to make the miles-long trek into elk country.

John Salazar is a Montana public land hunter, a board member of the Montana Wildlife Federation, and a stakeholder in CMAP where he represents the hunting interest. (He is not to be confused with the former Colorado Congressman.) Salazar has been vocal with his opposition to the 2019 lawsuit over prescriptive easements. He sees the land swap as a more viable way to secure access in the Crazies than fighting for prescriptive easements that might be too far gone.

“As it stands right now, [the proposal] definitely needs improvement. But consolidating public land is always the goal,” Salazar tells Outdoor Life. “I looked at the map and I see areas on there where I think you can get into elk, especially in bow season, within three to five miles of the trailhead if you were willing to do so. I know [the trail is] a journey the way it reads on the proposal, but it’s an opportunity to have a true backcountry experience. I think we’re starting to lose that a lot in Montana. There’s people everywhere you go.”

A Reputation for Trouble

Until recently, the public has relied on historic prescriptive easements to cross private parcels on the East Trunk and Sweet Grass trails. According to Montana law and the U.S. Forest Service manual, undeeded prescriptive easements are just as legitimate as deeded easements as far as public access is concerned. But once five years have passed without use or maintenance by the public or a federal agency, which in this case would be the Forest Service, the easement expires and the trail is considered abandoned.

Landowners with chunks of the Sweet Grass or East Trunk trails cutting through their property have tried to expedite that abandonment process by locking gates, posting “No Trespassing” signs, and requiring users to sign in with them before setting foot on the trails. (That last tactic forces the users to get landowner permission to access what should be freely accessible, reinforcing the argument that the easement has been abandoned.)

A regional supplement to the Forest Service manual, published in 1993, says that “Forest Supervisors are responsible for and shall: Continue to use, operate, control and maintain…existing roads and trails within the Region not covered by written easements…Monitor roads and trails that cross non-Federal lands, and when land management activities such as logging, road building, fencing, or signing/orange paint threaten to breach the facility or restrict National Forest use, immediately contact the landowner to prevent such breaches.”

The supplement goes on to say Forest Service officers may “assert Federal right-of-way ownership through such sections as citing the landowners for trespasses and removing privately installed signs/orange paint, gates, fences, or other barricades from the facility. When timber harvest or other landowner operations are anticipated to damage road/trail segments, the landowners should be notified in writing that the United States ownership rights need to be protected.”

But somewhere along the way, the Forest Service stopped trying to defend the trails and entered negotiations with the landowners instead, plaintiffs in a recent lawsuit say.

Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, Friends of the Crazy Mountains, the Skyline Sportsmen’s Association, and Enhancing Montana’s Wildlife and Habitat sued the Forest Service in 2019 for abandoning the two trails, among other issues. But their claims were dismissed in an April 2022 ruling, in which Montana District Court Judge Susan Watters opined that the court couldn’t compel the Forest Service to defend the trails, even though they’ve shown up on Forest Service maps since the 1920s.

Now, proponents of the land exchange argue that the Sweet Grass and East Trunk trails aren’t secure access points, for hunters or any other public land users. Hunters have used those trails for decades to access quality public elk habitat in Custer-Gallatin National Forest, especially because they are shorter and more feasible for packing out meat on foot. But so far, the land swap has been much more attractive to the Forest Service than enforcing those easements, let alone perfecting them in court.

“The Forest Service has made it very clear that they intend to give up all rights on the Sweet Grass Trail,” Sullivan says. “Once they do that, it will be virtually impossible for the public to reestablish our rights.”

In fact, nowhere is it clearer that the Forest Service is intent on handing Sweet Grass Canyon over to the landowners than on page 36 of the preliminary environmental assessment for the proposal. In the fourth paragraph, the federal agency seems to negate the intrinsic value of what is arguably the most beloved part of the eastern Crazy Mountains.

“The Sweet Grass Trail is a long out and back trail with no scenic destination.”

John Daggett was born and raised in Harlowton, Montana. He harvested his first cow elk in the Crazies at age 12 and his first bull elk in the same spot at age 16. He then went on to work for the Army Corps of Engineers, the Forest Service, the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Bureau of Land Management across a 39-year career. When asked about that sentence, he had choice words.

“They’re flat full of bullshit,” Daggett tells Outdoor Life. “That’s garbage. I’ve been up all the drainages on the east side, and I will tell you, the Sweet Grass is the most crowned jewel if you’re looking for Glacier Park-type views. That drainage is it.”

Just the Beginning

While hunter access organizations continue fighting for the Sweet Grass and East Trunk trails, John Salazar and Erica Lighthiser have made one thing crystal clear: CMAP and the Forest Service want to hear from the public. Both acknowledge that the proposal is not perfect as it stands right now and needs further work before it can best serve all parties.

“The public needs to speak out about the things they see that are lacking in the proposal, and it is lacking some things. Make sure that you comment, make sure that your voice is heard,” Salazar says. “We’re reaching a time when we’re going to have plenty of money in conservation groups, where we might be able to improve the access on the east side if this gets done. So I would say to people this is the beginning of something, not the be-all end-all.”