Two posts sit chained together in the middle of the Wyoming prairie, each bearing a “No Trespassing” sign. Nothing surrounds them. Not a fence. Not a road. Underneath the chain rests a metal survey stake marking the spot where four pieces of land come together.

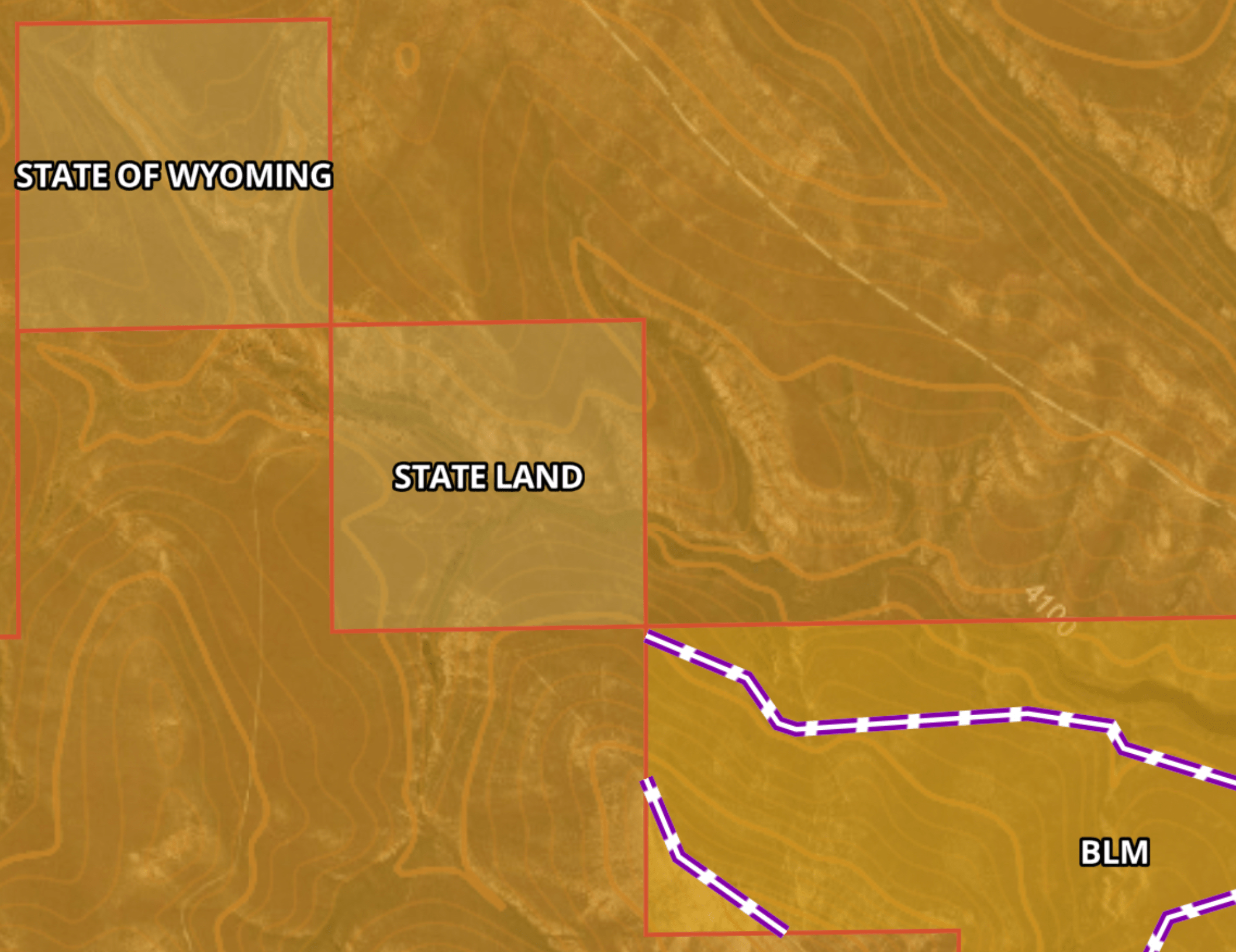

The Bureau of Land Management owns two of the pieces that touch at a corner. A private rancher owns the other two. The chain and signs are a clear signal: Do not cross here.

This season four men, all of them non-resident hunters, placed a ladder over that chain and crossed from one piece of federal land to another to hunt elk and deer, earning them a ticket for criminal trespass and the attention of sportsmen and women from around the nation. More than 1,300 people from as far away as Australia have donated more than $50,000 as of Saturday morning on a GoFundMe page to pay for their defense.

According to the GoFundMe page: “Brad Cape, Phillip Yoemans, John Slowensky and Zach Smith … have pleaded ‘not guilty’ and currently this case is pending. Corner crossing is a legal grey area that stems from the public’s desire to access their public land by stepping from one corner of public to another. We believe this act does not violate law or cause any negative impacts to private landowners and their use of their property. These four hunters took every precaution to make certain private land was not touched.”

That’s the thing about corner crossing. New GPS technology has created a world where hunters can pinpoint where lands intersect, and someone can step from public land to public land without physically touching any private land. But whether or not that’s actually legal in Wyoming is fuzzy.

“There is no specific law on the books at the federal level that either expressly permits or expressly prohibits this act of corner crossing,” says David Willms, the National Wildlife Federation’s senior director of Western wildlife, who spent years as an attorney in Wyoming’s attorney general’s office. “At the Wyoming level, there’s no statute on the book that directly prohibits or permits corner crossing either.”

Depending on who you ask, this case could help resolve an issue that countless Western hunters have been hoping to resolve for years. Though legal experts doubt it could pave the way to setting a precedent, many hunters are hopeful that a favorable ruling would allow hunters to access millions of acres of locked-up public land. It could also go the other way, formally prohibiting crossing any of those corners and expressly closing even the existing, albeit vague, practice of slipping across corners. Or it could be a whole lot of nothing.

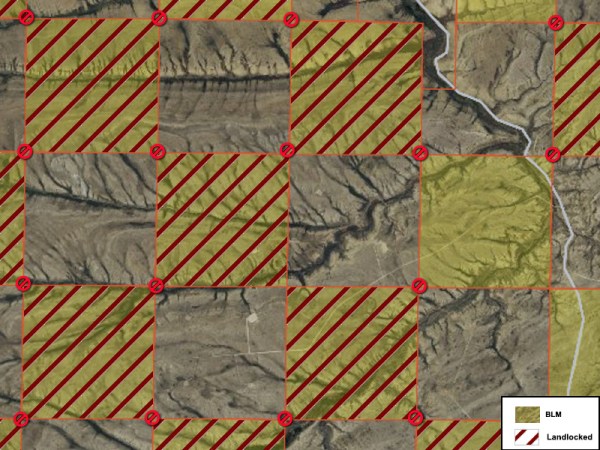

Locked Out of Public Land

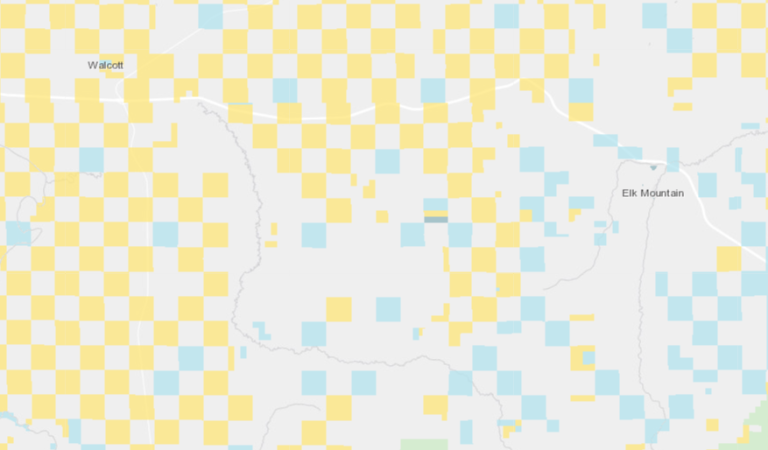

With 4.16 million acres of landlocked public land, Wyoming has the most inaccessible public acreage out of any state in the West. Some sections are thousands of acres, some no more than a few. Much of it is arranged like a checkerboard, a western anomaly dating back to when the fledgling United States wanted the West settled and railroads built to connect the country’s east and west coasts. Instead of dividing land by topography, as was often the case farther east, the federal government simply divided up hundreds of millions of acres into 640-acre parcels (1 square mile apiece) and handed them out. Much of that land was already occupied by Native American tribes, who were often forcefully removed despite formal treaties stating it was theirs.

The federal government then gave railroad companies like Union Pacific every other square for 20 miles on either side of its planned route. Railroad companies could borrow against the private parcels to help pay for construction.

The result is a big, curving paintbrush swath across western states full of hundreds of square miles of land that’s largely inaccessible to the public at a time when interest in hunting and other outdoor recreation is booming. In Wyoming alone, almost 2.3 million acres are locked up in this checkerboard pattern, according to an intensive survey conducted by onX Hunt and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership.

Most states explicitly state that walking, driving, or otherwise crossing private land to get to public land is some form of trespassing. Some, like North Dakota, grant hunters and anglers an easement across private land to access public. But what about when a hunter isn’t actually touching private land? Is it illegal to step over private land to get to public land?

Many hunters say no, many landowners say yes, and many legal experts say … maybe?

The Questionable Corner

This fall, four hunters from Missouri decided to risk it by crossing from one corner to another on that piece of land near Elk Mountain in southern Wyoming. They placed a ladder over the chain connecting two “No Trespassing” signs, and stepped up and over, from public land to public land.

They successfully killed elk and deer on public land, according to Jeff Muratore, a longtime Wyoming hunter who spoke with one of the hunters charged. At some point the four non-resident hunters were approached by the Carbon County Sheriff and each given a misdemeanor criminal trespass citation, which could come with a fine of up to $750 and 6 months in jail.

The specifics of the pending lawsuit are not public. Attorneys for the four hunters advised them not to speak to media, and Trevor Schenk, one Casper-based attorney representing hunter Brad Cape, declined to comment. The person who answered the phone for the landowner at Elk Mountain Ranch also said they had no comment. An undated real estate listing for that ranch says the ranch has no public access, citing “a U.S. Supreme Court decision on a ranch nearby which ruled it is trespass if you step over public sections of corners when private sections complete the corner.” (This is an unverified interpretation of the case mentioned below.)

Rick King, chief game warden for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, declined to add much more other than to say Game and Fish’s approach to trespass claims varies: case by case, and county by county.

So anyone speculating on what this current citation means for the future must rely on winding, messy case law.

And it starts way before the railroads, the checkerboard, statehood, and even the first European ship to anchor off the shores North America. The basis for landownership in the U.S. is often traced back to the 1200s and the Ad Coelum doctrine, a Latin term referring to common law of landownership. What Ad Coelum means, essentially, says Willms, is that “the landowner owns everything from heaven to hell, from the center of the earth to space.”

Except for the exceptions. Like planes. Landowners own everything underneath them—with the frequent exception of mineral rights—but everything above them becomes more complicated. Federal Aviation Administration regulations say that in rural, undeveloped areas, any airspace above 500 feet is public. Anything below 500 feet is the purview of the states to regulate.

Wyoming law then went so far as to say an aircraft is fine to fly over private land as long as it’s not “so low to interfere with existing use of land, water or use of space over the land,” Willms says. But it doesn’t give a specific elevation for that. So there’s no clue whether that’s 4 feet or 400 feet.

Wyoming and most other Western states also have exceptions for waterways. Someone can boat down a river through private land in Wyoming, for example, as long as they don’t touch the bottom. Exactly why that isn’t an issue in airspace is unclear, which is where the gray area becomes even grayer.

Landowners’ groups cite a U.S. Supreme Court case from 1979 between the U.S. and the Leo Sheep Company, which stated that “the Government does not have an implied easement to build a road across petitioners’ land.” But roads are not the same as stepping from one parcel to another.

In 2004, a judge in Albany County, Wyoming, found a hunter not guilty of trespassing when he corner-crossed to archery hunt elk. (In that case, the judge’s decision did not set precedent—it just found the guy not guilty.) Shortly after, Wyoming’s attorney general at the time wrote a decision offering the tiniest bit more clarity. The opinion reads that corner crossing doesn’t violate the state’s law prohibiting someone from crossing private land to hunt, fish, or trap public land, but it “may be a criminal trespass.”

So again: Hunters in Wyoming can be charged criminally for hopping from corner to corner—maybe.

A Legal Precedent for Corner Crossing Everywhere?

For the three Wyoming hunters and the Wyoming chapter of BHA—all who started the GoFundMe page to pay for the nonresident hunters’ legal fees—the issue is about a lot more than four guys from Missouri sitting with $750 misdemeanor tickets. It’s about trying to find some resolution to their own grievances as public-land hunters locked out of public land.

“We know that this case, no matter win or lose, is not going to set precedent. That has to happen at the appellate level,” says Buzz Hettick, a longtime Wyoming hunter co-chairman of the state’s Backcountry Hunters and Anglers chapter. “But what our biggest hope is, is that people recognize that access is a huge issue to sportsmen. And hiding from this thing on corner crossing is not going to solve the problems associated with it.”

Hettick, Muratore, and Pete Kassab are all clear that this is not an attempt to take private land. It’s about finding some resolution to a weird legal problem in the hopes of one day freely accessing all those pieces of public land that are sitting just out of reach for hunters.

It’s why they started the GoFundMe page. Based on the comments left by donors, it’s also why some of the more than 1,300 people have donated to the cause.

Jim Magagna, executive vice president of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, says the matter is settled through the 1979 Leo road case, and trying to cross corners is an infringement on private property rights.

“Saying ‘we stepped across it’ to me does not meet the legal test or practical test that you didn’t trespass on my property,” he says. “You may not be physically harming the land because you didn’t put your foot on it, but I would contend that you are interfering with the private property rights with the owner of the land.”

He does agree, at least, that corner crossing is a problem in many Western states, and would like to see resolution.

Randy Newberg, a Montana hunter who’s spent decades focused on the issue, understands the desire to fight the criminal trespass citation. He understands—and shares—frustrations by hunters that all this public land—16.43 million acres in 22 states—is out of reach. But he isn’t so sure this will result in the outcome everyone desires.

First, a ruling likely won’t create a precedent for anyone outside of Carbon County, Wyoming, and maybe not even then. Theoretically, if the men are found guilty of criminal trespass, they could appeal the ruling to a higher court and ultimately end at the Wyoming Supreme Court. Even in that unlikely scenario, the decision by the Wyoming Supreme Court would only apply to Wyoming, despite the fact that the public land in question is federally owned.

The only way it could set precedent outside of Wyoming is if the federal government gets involved, something Willms and other attorneys say is also very unlikely.

Read Next: WSA21-01 Is Back, and It Could Close 60 Million Acres of Public Lands in 2022

In the meantime, worries Newberg, lawmakers in states like Montana, Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming will look at this case and decide that it’s time to set formal laws penalizing the practice.

No court date had been set as of Wednesday. So what hunters know right now, is the case could either be dismissed or go before a judge or jury in a rural county in Wyoming, with the ever-so-slight chance it could help settle one of the West’s messiest public land issues—in Wyoming, at least.