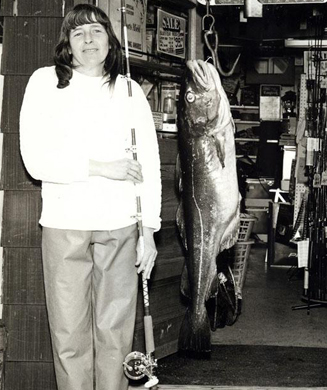

Billy Sandifer was a legend. During the Vietnam war he was exposed to agent orange, resulting in a slew of health issues. In 1977, he decided the best medicine was to retreat to Padre Island National Seashore in Texas—one of the largest expanses on undeveloped beach in the world—and live there alone with the coyotes. Over the next few years, Sandifer kept busy pioneering tactics for land-based shark fishing, a fledgling sport that was well off the radar of the masses. Sandifer routinely beached massive tiger sharks and hammerheads in quiet seclusion. But he wasn’t the only one playing this game.

For decades, a devoted underground network of land-based shark anglers has existed across the Gulf and Southern Atlantic States. For the most part, these thrill seekers kept to themselves. More importantly, they kept what they did largely out of the public eye. My good friend, Zach Miller, grew up in the 90s targeting monster sharks off the beaches and piers of South Florida. He was deeply embedded in that cult, but as he puts it, “We did everything under the cover of darkness. We left no trace that we were ever there.”

There was a strong conservation ethic among land-based shark anglers of Miller’s era, and a mutual understanding that if you wanted to continue doing what you loved, you stayed out of the way of tourists and you didn’t make a scene. Fast forward to 2022, and land-based shark fishing has become one of the most overblown, ego-driven gong shows in fishing. All this commotion is destined to destroy the sport, for what’s left of serious scenesters from bygone years.

A Privilege, Not a Right

On August 8, the New Jersey shore town of Sea Isle City officially outlawed targeting sharks from its beaches and jetties. According to the Asbury Park Press, violators can face a $1,250 fine per occurrence. This news is quickly circulating throughout the Northeast, as Sea Isle is the first city to ban the sport in the region.

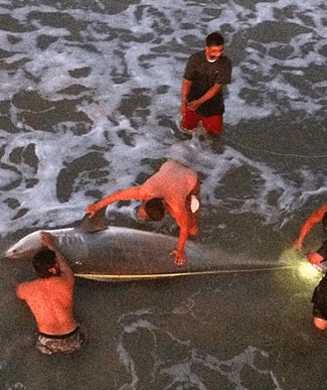

Frankly, it’s a laughable development to dyed-in-wool, land-based shark anglers in the South, who have watched town after town outlaw sharking on public beaches and piers. But the reason for these closures is the same in the Northeast and the South: A new generation of social media heroes has adopted the sport, and many treat their ability to target sharks from the beach as a right. They lack the forethought and respect of earlier generations to consider how the public will react to seeing a shark dragged onto the beach in the middle of the day.

This past July, while sitting on the beach in Ocean City, New Jersey, with my wife and kids, I watched two bros drag a kayak and heavy spinning outfit down to the water within 100 feet of the lifeguards and designated swimming area. They butterflied a whole menhaden, pinned it on a steel wire rig, and I watched the one fella struggle to paddle it out past the breakers. I couldn’t help but chuckle, because this was done so haphazardly, and I questioned whether the reel they were using could even handle a small shark. They didn’t catch anything, but I’ve been on the same beach when others have.

Two summers ago, a group of anglers connected with a 60-pound brown shark right in front of me. A crowd gathered in no time. When people realized it was a shark, swimmers quickly cleared out. For some onlookers, this was exciting. But I listened as moms raised concerns about sending their kids back in the water. My own daughter (who lives to swim) understandably got the jitters. I had to explain that the kind of sharks that live here aren’t likely to hurt you. In the Northeast, you’re most likely to hook brown and sand tiger sharks in the surf, both of which are fairly harmless and generally docile. Compared to what Southern anglers reel in, these sharks are also pretty small, yet the social media bravado around catching them is massive. Never mind that it’s technically illegal to target both browns and sand tigers.

Brown and sand tiger sharks are both protected species in Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey, but this doesn’t stop anyone from targeting them. Every angler I talk to from Cape Cod to Cape May tells me the uptick in folks sharking from shore is so noticeable that these anglers are becoming a plague on beaches. Wildlife agencies recognize that protected sharks will inevitably be hooked as bycatch by anglers looking for other species, which is why states like New York have created a set of guidelines for safely and quickly releasing a protected shark. One thing all the rules stress is not dragging a shark up on the beach, and not delaying its release with photos. But not only are anglers taking plenty of photos of protected sharks, they’re sending them to news outlets, exacerbating public concern.

This summer, there have been more stories about sharks being caught on Northeast beaches than can I ever recall. They’re coming from New York and more recently (drum roll), Sea Isle City, New Jersey. What most of these stories have in common is that they omit everything about the treatment of the sharks or their protected status, and instead prey upon that little bit of Jaws-born fear in every ocean swimmer.

Per this story in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Sea Isle City ban was prompted by residents who were concerned that anglers were attracting more sharks to the beach. This is actually an unfounded worry. The idea that putting bait in the water brings in sharks is inaccurate. Browns and sand tigers naturally live and feed tight to the beach. In other words, they’re already there and banning fishing won’t make them go away. But you can’t rely on the non-angling public to educate themselves. In my opinion, it’s the burden of the angler who does have knowledge of the species to not scare the shit out of the non-fisherfolk.

I’ve got nothing against land-based shark fishing. In fact, I’ve had the pleasure of doing it with a veteran crew in Florida, which resulted in me catching a 10-foot hammerhead—the biggest fish of my life. But the goal was catching a shark, not attracting a crowd—and definitely not getting on the news. If you truly loved catching these fish and not the attention, you’d be out there at night. You’d go out of your way to find less crowded, more desolate beaches (and plenty exist.) Otherwise, what’s happened in many Florida towns and now in New Jersey will continue until what used to be a cool underground scene is an illegal activity everywhere.