In a recent interview with BBC Radio, director Steven Spielberg expressed remorse about how his epic 1975 film, Jaws, negatively shaped the public’s perception of sharks. Jaws did, after all, paint the great white as a vengeful creature, intent on singling out humans to satisfy its unquenchable thirst for blood. That portrayal made Jaws terrifying, and subsequently one of the most acclaimed and widely viewed films in the horror genre. It is hard to deny, of course, that interest in recreational shark fishing spiked after Jaws. The late 1970s and early 1980s are considered by many offshore anglers the heyday of shark fishing, and with minimal regulations, or a complete lack of them in some regions, most of the time a caught shark was a dead shark.

In those days sharks were hung up at the marina scale for crowds to gawk at, regardless of the food value of the species.

“That’s one of things I still fear. Not to get eaten by a shark, but that sharks are somehow mad at me for the feeding frenzy of crazy sportfishermen that happened after 1975,” says Spielberg. “I truly and to this day regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film. I really, truly regret that.”

It’s true that shark populations are in trouble the world over these days. Many species, including the great white and, more recently, mako sharks along the Eastern Seaboard, have been given protected status and made off limits to recreational and commercial anglers. The reality, however, is that while Jaws may have fueled the recreational shark fishing fire, it was not the spark that ignited it, nor is it the strongest flame still burning down shark numbers.

Monsters Are Real

The shark in Jaws may be the most psychologically disturbing monster in horror history, and the reason for that is simple. King Kong, as an example, terrified viewers when it was released in 1933, but no one was genuinely worried about a gigantic ape attacking their city. It was just too fictional. But Lake Placid depicted a giant saltwater crocodile consuming bathers, and Anaconda showed us Jon Voight getting regurgitated by a 40-foot snake. Both of those animals exist in the real world, it’s just that most Americans don’t put themselves in habitats where they live. However, most of us spend time on the beach and swim in the ocean, and Jaws reminded us that we can’t always know what’s swimming out there with us. While the shark in the film was bigger than average, great whites large enough to consume a human exist along almost every coast on the planet.

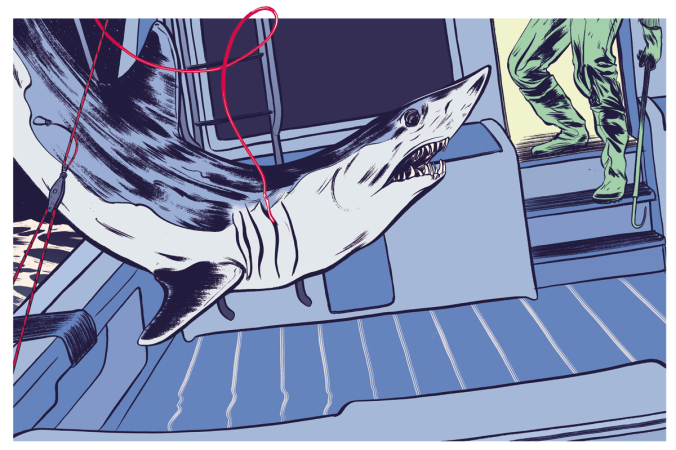

Captain Frank Mundus was one of the first people to ever capitalize on the public’s fear of sharks. In the 1950s, while running charters for bluefish off Montauk, New York, Mundus noticed the abundance of sharks in the area and shifted his business model. He began offering “monster fishing” trips. He advertised by routinely hanging huge great whites, threshers, and makos at the dock, becoming somewhat of a tourist attraction in the seaside town. Eventually, Jaws author, Peter Benchley, would wind up on Mundus’s boat, and although Benchley never officially confirmed it, it is widely believed that Mundus was the inspiration for the Captain Quint character. It was this meeting between the self-proclaimed “Monster Man” and the novelist that would change the course of recreational shark fishing.

Cheap Thrills

Guys like Mundus existed all over the country before Jaws, it’s just that their numbers were relatively small. The charter fleet in Florida was always happy to let Midwest vacationers crank on tiger sharks and hammerheads, and just the experience of catching a 10-plus-foot fish was thrilling for tourist anglers. A lack of edibility didn’t matter, but that wasn’t the case for fishermen elsewhere.

Where I grew up in the Northeast, mako sharks were as coveted for the table as tuna and swordfish. On both the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts, there had always been a contingent of offshore anglers who treated them with reverence and respect. What Jaws did was draw more thrill seekers to shark fishing than serious anglers, prompting more captains to focus on sharks, and new captains to jump into the game to grab a piece of the action.

Ironically, whereas Spielberg and others believe Jaws started the downfall of sharks, I credit the movie with my deep love of fishing. It is my all-time favorite film that I’ve been watching since I was about 6 years old. Quint and the shark planted the notion that there are bigger fish to catch than the bluegills and stocked trout I knew. Jaws created aspiration.

In my opinion, hook-and-line anglers have never been as damaging to shark populations—even in the post-Jaws era—as mass harvesting. After all, only so many large sharks can be hooked in a single day on the water with a few lines out. But the fear created by Jaws also lead to beach communities around the world using everything from miles of entangling nets to long lines in attempts to rid large stretches of coastline of sharks in order to make bathers feel safer. Thankfully, much like how recreational fishing regulations have been drastically altered to protect sharks, new technology is making it possible to repel sharks instead of kill them. Why then are these fish still in so much trouble? At this point, it has little to do with a movie and much more to do with greed.

Stop the Shark Finning

Just recently, the US House of Representatives approved legislation to ban the buying and selling of shark fins in the United States. Shark fin meat is considered a delicacy in many Asian countries, where it can fetch incredible amounts of money. It has been outlawed by many nations and is highly regulated in others, but as it goes with any trade, if there’s money to be made, rules and laws will often be skirted. What’s so brutal about shark finning is that no species is safe—any shark that comes aboard is finned alive and its body is tossed back into the sea. By discarding the body, more space is created onboard for more fins, which means more sharks can be killed in a single trip. And while there isn’t much of a market for shark fins in the U.S., this illicit practice still takes place in our waters to supply the foreign market.

From Thehill.com: “This bill will finally remove the U.S. from the devastating shark fin trade once and for all … [and] will also help to fight illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing by giving the U.S. more tools to take action against countries that fail to address these devastating and destructive practices in their fleets,” Oceana’s Beth Lowell said.

Although this is a great step in the right direction, the sad reality is that we’re a long way from ending shark finning on a global scale, and this trade stems in no way from the fear or thrill-seeker curiosity created by Jaws. Take the practice out of the equation, and shark populations could rebound over time, because while there was certainly damage done in the past by recreational anglers, attitudes have now largely shifted and regulations have changed. Fishermen are arguably more in tune with the plight of these fish and have more respect for them than ever before, so in a strange way it can be said that Jaws also led to this stronger conservation ethic. It created more shark anglers, and over a generation Jaws ended up being the catalyst for the complete debunking of the idea that all sharks are hellbent on killing you.