Editor’s Note: If there’s one thing that’s certain after these last few weeks, it’s that Americans need to come together. To do that, we first must listen to those of us who have been ignored for too long. At Outdoor Life, that means black and other minority hunters and anglers who don’t often see themselves represented in the hunting and fishing community. We’re running a collection of essays to tell their stories and share their perspectives.

I’m a diehard bird hunter and dog man. I love everything about it: The discipline and patience it requires, the glorious days in the field, and the long, storied history behind it all. But as an African American dog man living in Georgia, I know that there’s a large hole missing in the history of bird hunting and dog training. That hole is created by stories unheard and untold to the general public.

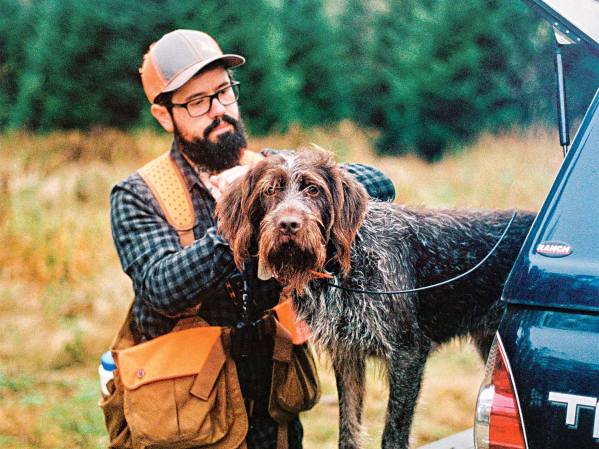

I got into bird dogs after my introduction to hunting, and immediately felt the loneliness of working by myself to train my dog to hunt. Being from Atlanta, I did not see many black folks with bird dogs, and it’s not often that you’ll pick up a magazine and see us in there. There had been little to no minority representation in the hunting community and even less so in the bird dog world. That, however, seems to be changing. One day I flipped through a magazine that I usually read for the Southern culture and stumbled across images of a world hidden deep within the depths of the South Georgia’s piney woods: the world of black bird dog trainers.

This sparked my curiosity, and for the last four and a half years I’ve been on a journey to better understand my connection to bird dogs, and my natural love for them. I’d been trying to figure out why I’m so drawn to the images of Neal Carter and Curtis Brooks Sr. riding horseback, pointers on their tailgates (below, you can watch the feature film Project Upland created to see what I’m talking about). When I look at those photos, I get those same feelings that young black athletes have when they see clips of Michael Jordan playing basketball or watch Tiger Woods take the lead at the Masters. Those feelings resonate within our community as we tell ourselves, “I can do that too!”

I’ve always felt the need to have a dog. Years ago I kept pit bulls and trained them to do all sorts of things, from basic obedience to protection. This was out of necessity as I grew into adulthood and started living on my own in areas where random door knocks happen at 2 a.m., unwarranted and unexpected. My dogs would bark back loudly, the hair on their necks raised. As I transitioned from pit bulls to bird dogs and connected with the images of little-known black dog men who were few and far between, the question haunted me still: What is it about a dog?

Recently I found a story in the beginning of Scott Giltner’s book about African American plantation life, Hunting and Fishing in the New South: Black Labor and White Leisure after the Civil War, that might hint at that answer. It opens with a former Alabama slave, Heywood Ford, recounting the tale of fellow slave Jake Williams, who became fed up with his living conditions and the officer in charge of the plantation (go figure). Jake and the plantation’s overseer were always at odds and Jake planned to make a run for it. But he had one precious piece of business to take care of first—his Redbone coonhound, Belle.

Knowing that he couldn’t take her with him, Jake asked Heywood to keep Belle and care for her. Unfortunately, it didn’t take long before the plantation overseer got wind of Jake’s escape and set out in a search, unleashing a pack of hounds to find and catch the runaway slave. It also didn’t take long before Jake was up a tree with a pack of dogs at its base. The overseer climbed up the tree to pull Jake down and, in his desperation, Jake kicked the man to the ground. Upon crashing down, the overseer was mauled by the pack of hounds, which shocked Jake. Hounds would never attack their owner—would they? Then Jake noticed that the lead dog was none other than ol’ Belle, who realized the man she’d treed was also the man who cared for her, and raised her with care and compassion.

Ain’t that ‘bout a thing, I thought to myself.

I’d been working a Labrador and a pointer for years in hopes of emulating and mastering the work that so many of my African American forefathers had done so well during the worst of times. During my own hunts, I’ve seen it all click, when the dog work comes together in ways that gives me a reverence for nature and the power of my dogs. Some of these hunts I’ll never forget. Like the first time I decided to bring my Labrador, Ruger, on a wild quail hunt that was supposed to only be for Vegas, my pointer.

Vegas was young, inexperienced, and needed wild bird contacts. But he also needed birds to fall in order to put all of the pieces together. We’d gone out once before on the same wildlife management area and found, pointed, flushed, and missed roughly six coveys of birds. I still beat myself up over that day. I was over-choked and shooting under the birds every time.

The young pup had done his job and I had failed him miserably. That silent, “I,” in team wasn’t holding up his end of the bargain. This next trip had to count. All I could think about was getting another chance, and ran through the hunt again and again. It was December, but still plenty hot, which meant thick ground vegetation, brush, and thorns pierced my Double Tin chaps with ease. I knew once I’d screwed in the proper chokes in my 20-gauge I’d be in the game and birds would fall. But who would pick them up?

I don’t let my pointer retrieve birds for field trial conditioning, and I certainly wasn’t about to get on my hands and knees looking for downed birds that were notorious for running out their last breath. So I figured that day would be the first day I’d run my pointer and a flushing retriever together.

I let both dogs off the tailgate and gave Vegas the go-ahead and kept Ruger at heel as we walked through the piney woods. The good thing about bobwhites is that they usually do not stray far from where you found them last time. And the good thing about smart bird dogs is they remember where they last found the birds. All was in order after a few minutes of walking.

The Garmin collar vibrated and I’d looked down at Ruger and said, “Your buddy’s got his part down, now time for you to get ‘em up.”

We walked into the point and I released him from heel by his name to flush the quail. In no time they were up. I’d worried that there would be competition between the two dogs, and we’d have a meltdown. But there was no time for that worry now. I fired at a blur of flushing feathers and connected. Vegas gave a little chase, as he was not broke to shot in those days, but he let Ruger retrieve the downed bird. The whole scene lasted seconds, but it will last forever in my memory, and to this day I hunt both dogs together. They understand the notion of teamwork and being connected. Everyone has a job, and everyone gets rewarded when the job is done well.

Nowadays we guide other hunters and have received a multitude of compliments from guests of the hunting club. They love our unified effort to deliver an exciting experience over class dogs, and at the end of the hunt the guests always thank the dogs—and I thank them as well.

My African American forefathers found a connection to their dogs that, in some ways, were much like themselves. Dogs, like the black men of those days, were quite proficient in their hunting capabilities, but they were seen as tools and subjected to lesser treatment. But we, as African Americans, understood the brutality of the world around us and placed our faith in similarly disregarded, yet loyal, beings. We connected with our hunting dogs—hounds and bird dogs both—in ways that could never be fully described in written word. So we told stories. Like all hunting tales, they were sometimes highly dramatized. But still, they served as parables to teach the upcoming generations of dog men and women in our community.

Read Next: The Vanishing Legacy of Southern Rabbit Hunting

The story of Jake and Belle, like many stories of old, is likely touched with a little more sauce than what actually took place. Yet that story is still true, in the deepest sense, in the hearts and minds of black folks. This is how we teach. This is how we’ve learned. And still, decades later, our oral history is being passed on to bring up our next generation of black bird-dog trainers.

It gives me great hope to uncover more of our stories—ones that reveal the strength and ambition that permeates African American history, and that drive me to keep uncovering old stories and find a place for these narratives in mainstream culture. These stories can no longer remain hidden and unfamiliar. These stories make me a better dog man. I know that the resilience and creativity of my ancestors helped lay the foundation for the hunting dog training that I am committed to today. As for the rest of the hunting community, hopefully these stories force us as Americans to confront the ugly past, which brought that plantation overseer to the base of Jake’s tree. It’s time, America, to come off the tree and together, equally, we can let the dogs do their work.

Durrell Smith is a 30-year-old native of Atlanta, an author, visual artist, art teacher, bird dog handler/trainer, and most notably, the host and founder of The Gun Dog Notebook Podcast. He writes mainly for Project Upland and is also a member of the Ga-Fla Shooting Dog Handlers Club in Thomasville, Georgia.