The airport ticket agent paused when she printed out my baggage tag.

“Where in the world is ABR?”

When I told her it is the code for the regional airport in Aberdeen, South Dakota, she shrugged and placed the tag on my gun case.

“I’ve never heard of it.”

Obviously she’s not a pheasant hunter.

The first Chinese pheasants in North America were released in Oregon’s Willamette Valley in 1881, but the edge-dwelling upland birds fared better in the wide-open spaces of the American Great Plains, where shotgunners have been pursuing them for the last century.

More than any other state, South Dakota has embraced the ring-necked pheasant, and the state earns significant revenue from the 150,000 upland hunters who bag more than a million roosters there every year. The bird is as much a symbol of that state as the bison and the presidential figures carved into the face of Mount Rushmore.

While the number of put-and-take operations featuring captive-raised pheasants is growing in South Dakota, this remains one of the last places where large numbers of wild birds thrive, thanks to classic habitat: wetlands, small-grain fields, and expansive blocks of intact grass that stretch across the rolling plains.

And more than any other city in America, Aberdeen is a town defined by the rooster pheasant. In Brown County, where Aberdeen is the county seat, hunters harvested more than 87,000 birds in 2012, and 68 percent of the pheasants harvested were taken by nonresidents, who dropped $12 million in that county alone.

Rooster Town

The gaudy Asian bird shows up in just about every facet of the town’s identity and history. The Golden Pheasant Festival of the 1940s brought big-screen talent to the prairie town, and the now-defunct Aberdeen Pheasants was a talent pipeline for the Baltimore Orioles. Today’s NAHL affiliate is called the Aberdeen Wings, and its cocky mascot is named, predictably, Winger.

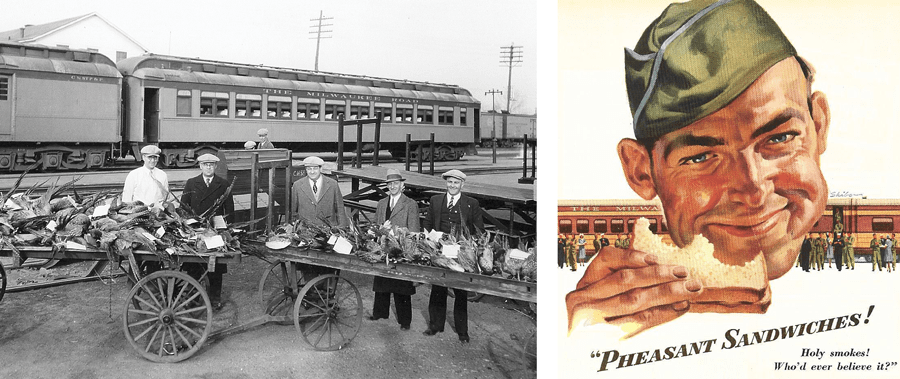

Visitors arriving at ABR are greeted by a 7-foot statue of a wild-eyed pheasant and a banner advertising a million-dollar prize if you shoot “Ringneck Rodney,” a banded rooster that must curse the bounty on his spurred leg. The airport is crowded with hunters in brown duck and blaze orange, and as one shotgun case after another rolls off the baggage belt, locals hand out traditional pheasant sandwiches to hunters. Welcome to Pheasant City, USA.

When a hunting trip starts out this way—the sandwiches passed around on opening day are a nod to treats that locals served to World War II troops passing through town—one’s expectations are pretty high. Happily, they weren’t misplaced. By the time we started our first hunt, I’d seen no fewer than a hundred birds picking over the harvested fields and standing in small groups at the edge of Highway 281.

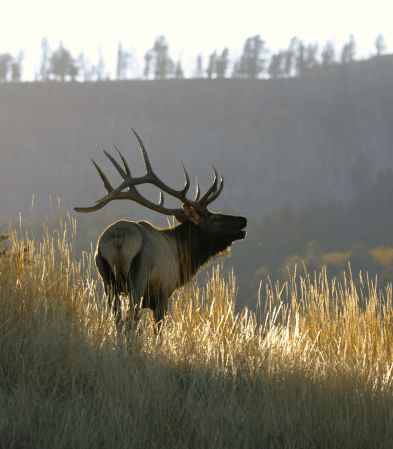

On my group’s first pass through a patch of CRP ground, we flushed roughly 30 wild birds, all rising up with drumming wings and cackling out across the steel-gray sky. For a guy like me, who learned the trade on released birds, these wild roosters were blindingly fast, exploding from cover and blitzing across the fields in a blur of color that left me clipping tail feathers on my first few attempts. Despite my initial failures, I had plenty of opportunities to get the hang of timing my swing until there was sufficient daylight between the bead of my Franchi and the bird. Hens are off-limits in South Dakota, so learning to pick out a rooster and then shoot before he beats out of range is a special challenge, but it’s one that brings thousands of hunters to Aberdeen each year.

“Hunting—and hunting wild pheasants in particular—brings a much-needed economic infusion into small-town South Dakota,” says Charlie Wonhof of Full Circle Lodge, located outside Aberdeen. “More habitat equals more pheasants equals more hunters.”

CRP Acreage Declines

South Dakota’s best pheasant habitat is associated with private land enrolled in the federal Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). The unharvested grasslands are important to upland birds, providing food, security cover, and brood habitat. CRP ground also reduces erosion of the thin prairie soil, filters ground water, and provides habitat for a variety of wildlife species beside pheasants and grouse.

But 10 million acres of CRP have been lost in South Dakota since 2007, and current CRP acreage is the lowest it’s been since the late 1980s. This is due largely to money. Farmers, lured by lucrative commodity prices fueled by export demand and ethanol subsidies, are taking land out of CRP and planting it to corn. As ag commodity prices increase, more CRP ground is tilled under, and biologists predict reductions in the wildlife-carrying capacity of large blocks of the Great Plains.

Research has shown that fractured habitat can have a negative effect on survival rates for birds, which tend to be more stressed and vulnerable in smaller plots of land. Nearly everywhere row crops fragment large stands of native grass, pheasant survival rates drop significantly.

Across the Dakotas, high pheasant numbers track closely with large blocks of CRP ground, and support for CRP unites some odd bedfellows: wingshooters, environmentalists, and Main Street businesses. Aberdeen merchants know that as the ring-necked rooster goes, so goes the regional economy.