The wild turkey’s return to Nebraska is one of hunter-based conservation’s great success stories. Six decades ago, there were no turkeys in Nebraska. Now Nebraska’s turkey flock is a puzzle for scientists. The reintroduction of wild birds to Nebraska—many of which had mixed with domestic birds—has created a genetic tapestry researchers are only just beginning to unravel. Many traveling hunters know that you can kill a Merriam’s, Rio Grande, and Eastern gobbler in Nebraska. But how pure are those subspecies? The first documented release of wild turkeys in Nebraska occurred in 1959, when 28 Merriam’s birds were translocated to Pine Ridge in the northwestern portion of the state. Although the Merriam’s subspecies was not believed to have been previously present in Nebraska, that flock flourished and quickly expanded their range into southeastern Wyoming and South Dakota. Two years later, 518 Rio Grande/domestic hybrid birds were released in the riparian forests in the central and south-central portions of Nebraska deemed suitable turkey habitat. That release was much less successful, and in many areas, the efforts failed completely. The success of the Pine Ridge Merriam’s flock prompted biologists to transplant some of those birds for release in other portions of the state, where they continued to expand their range and hybridize. In the southeastern portion of the state, the remaining Rio Grande birds from the 1961-62 release colonized suitable habitat, and the release of Eastern wild turkeys in the extreme southeastern corner of the state further tangled the branches of Nebraska’s wild-turkey family tree. IDENTIFYING NEBRASKA’S BIRDS Many turkey hunters don’t care which subspecies they’re after, so long as they gobble and strut. But two groups in particular have a vested interest in the DNA of Cornhusker turkeys. One is hunters seeking a Grand Slam, recognized by the National Wild Turkey Federation. A Grand Slam requires one of each of the four major U.S. subspecies of wild turkey (Osceola, Rio Grande, Eastern, and Merriam’s).

The other group is a team of scientists from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission and the University of Nebraska at Lincoln. Using DNA analysis, these biologists are unraveling the genetic composition of turkeys across the state. This research has the potential to explain which subspecies of turkeys have been most successful, how certain subspecies have adapted to varying habitats across from the Sandhills to the agricultural areas, and whether hybridization of wild birds with domestic turkeys has affected survival rates.

A COMPLEX LINEAGE

Differentiating between turkey subspecies is a complicated matter, even when DNA is analyzed. Essentially, a wild turkey is a wild turkey, and even morphologically identified subspecies like the Rio Grande and Merriam’s birds share so much of their DNA that they are almost genetically identical.

The genetic testing to date is consistent with the historical record that, over time, bird populations have intermingled and muddied the genetics.

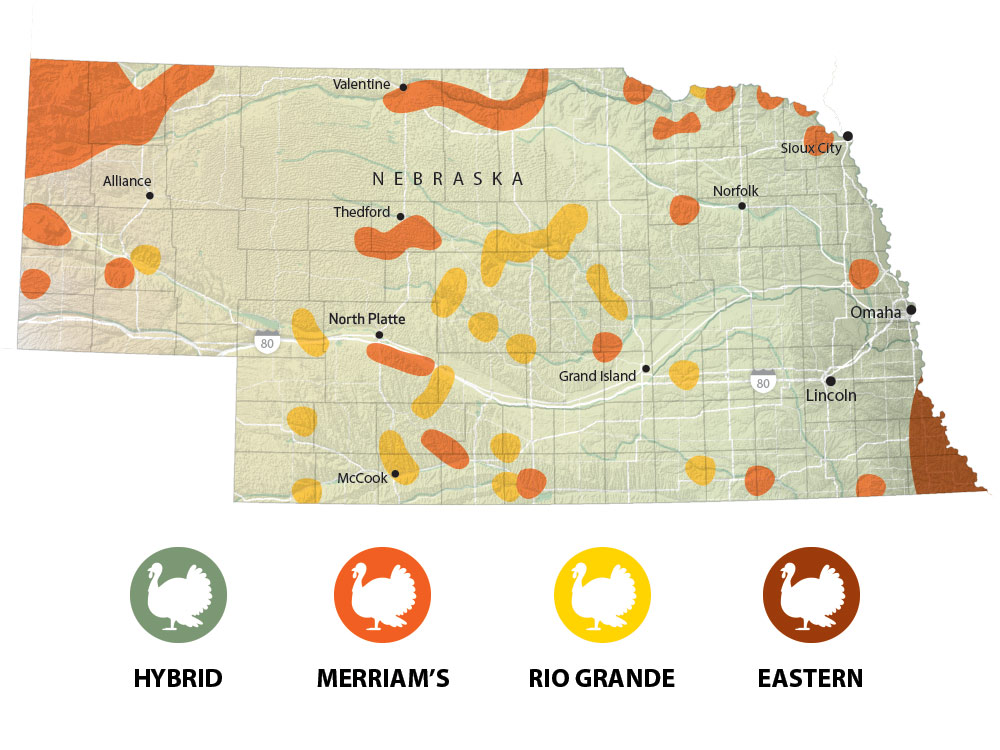

Evidence shows that turkeys in the western portion of the state exhibit traits from western turkeys (including both Rio Grandes and Merriam’s), and birds in the eastern half of Nebraska are more typically Eastern wild turkeys. The most concentrated western stock birds (no surprise) are found in the northwestern portion of the state, and the birds from the southeastern corner primarily exhibit characteristics of Eastern birds. Outside the Pine Ridge area, most wild-turkey populations in Nebraska include at least some birds with domestic DNA.

WHAT IT MEANS FOR HUNTERS

If you’re going to Nebraska looking for an Eastern gobbler, then you need to concentrate your efforts along the southeastern edge of the state. The western half of Nebraska is home to birds with all three haplotypes, and so many of the turkeys are hybrids. Your odds of success on a Merriam’s—or at least a bird with a white-tipped fan—are highest in the northwest because it’s well-documented that the birds released at Pine Ridge were Merriam’s. And if you’re looking for a bird with Rio Grande features, focus on the southern and southwestern portion of Nebraska, where Rio Grande hybrid birds were released in the 1960s and where modern DNA evidence reveals birds with western blood.

But the bottom line is that wherever you’re hunting in Nebraska, you can find turkeys with genetic characteristics of more than one subspecies. You’ll need to base your identification—and your Grand Slam bragging rights—more on appearance than genetic analysis. For most of us, that’s just fine.

Read Next: Top 10 DIY Western Hunts

What’s in a Grand Slam?

Wild turkeys now inhabit every county in Nebraska. Per the National Wild Turkey Federation, hybrid birds can be classified as the subspecies that they most closely resemble, and so hunters technically can shoot 75 percent of the Slam in Nebraska—but knowing where to look can dramatically help your odds.

Centuries of Strutting: A Nebraska Turkey Timeline

1804

Lewis and Clark report seeing wild turkeys in what is present-day Nebraska.

1915

Wild turkeys are considered all but extinct in the Cornhusker State.

1937

The Pittman-Robertson Act provides much-needed funding for wildlife-restoration work. 3

1945

World War II ends, and serious wild-turkey-restoration efforts soon begin across the United States.

1951

Cannon nets allow for highly effective trap and transfer of wild-turkey flocks.

1959

Twenty-eight Merriam’s turkeys are released at Pine Ridge. They flourish.

1961

Rio Grande hybrids and Easterns are introduced in other suitable habitat areas in Nebraska.

Today

Nebraska has one of the country’s highest turkey populations—albeit with a bunch of hybrid birds.