If you live somewhere in pheasant range or travel there to hunt, one word permeated your thoughts and your discussions with hunting buddies over the summer: drought.

Across much of the core pheasant range, dry weather in late spring turned into the prospects of a drought by early summer and devolved into a downright extreme situation by late July and August.

Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa (and in roughly that order) were hit hardest. Farther south, Nebraska and Kansas didn’t totally escape some level of drought conditions.

The drought equation for upland birds is at once simple but scary. Dry and warm weather is good for hatching nests and raising broods. But conditions that devolve into drought begin to affect habitat quality and quantity. Habitat doesn’t grow as well or become as lush, food sources (high-protein insects) may dry and disappear, and producers need to hay or graze to keep livestock and livelihoods alive.

Of course, among hunter circles, there are always your Eeyores (the it’s all over and there ain’t no pheasants left crowd), as well as your Polyannas (the quit-yer worrying everything is gonna be great crowd).

Reality falls somewhere in between. Conditions also depend on the state you hunt or are considering hunting, and even specific regions within each state.

That’s what Pheasants Forever’s annual state-by-state Pheasant Hunting Forecasts are all about: Starting down your research road for this year’s hunts. Go to the page, click on a state and get your footwork started.

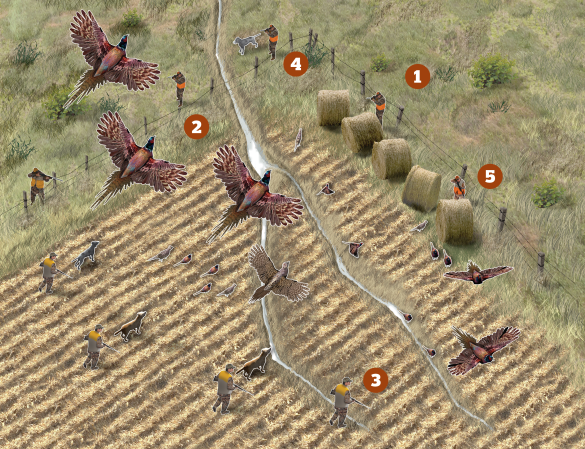

But here’s a shorter rundown: The Polyannas win out over the Eeyores. Bottom line is, there will be birds to hunt. But do your research, make your calls ahead, don’t expect the habitat to look like it did in the past, and expect to hunt. Here’s a bird’s-eye view.

Montana and North Dakota got hit hardest by drought, and of the core pheasant states, hunting will be most challenging on the far northern plains.

Minnesota will have birds, and in localized places, maybe more than one would expect.

Iowa, the up-and-coming pheasant hunting powerhouse state, fared fairly well.

South Dakota obviously will have birds, but since roadside pheasant surveys were suspended there, it is hard to put real data on the ground to direct your hunt. Public land hunters will work harder than ever for birds and must be prepared to find habitat that is few and far between.

Kansas and Nebraska will be about like last year, which is to say fair to good depending on region.

And as noted before: Everywhere, beware. Emergency haying and grazing happened. Habitat is going to look and feel different. Do not be surprised at what you find. Be ready to drive … and then to walk.

The scariest year of a drought for upland birds is not year one, when hunting is still fair to decent. What bites hard are the following years, when the habitat is degraded and the birds don’t have as much to start with.

In the end, it all comes down to available Habitat. Despite the ring-necked pheasant’s survival grit and determination and resiliency, the birds’ prospects are only as good as the habitat available to them. That is just simply what Pheasants Forever does. Since inception, PF has impacted over 21 million acres of habitat, and created over 215,00 acres of permanently public wild places to hunt and recreate. Upland wildlife habitat and public lands need you.

— Tom Carpenter is the editor of Pheasants Forever’s Journal of Upland Conservation.