We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

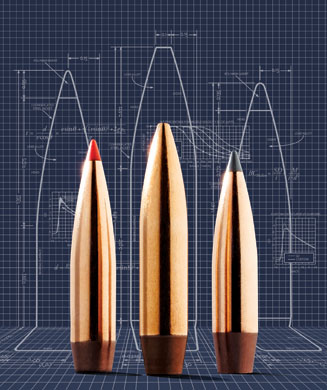

Photo by Stuart Fisher

The performance specifications used to describe most shooting equipment is easy to grasp. With rifles, we have trigger weight and length of pull. On scopes, we talk about magnification and objective lens size. Bullets are bit trickier, however. The common performance attribute for projectiles–ballistic coefficient (BC)–is more difficult to understand. Here’s what it is and how it is measured.

Ballistic coefficient is the number used to determine how well a bullet flies; in particular, how well a bullet will retain velocity.

Retained velocity may not seem as important as drop, or wind drift, or kinetic energy (KE). However, retained velocity fundamentally affects every aspect of external ballistic performance. A high BC bullet retains velocity well and will have less drop and wind deflection, and it delivers more KE to a distant target. Understanding BC is critical for any type of long-range shooting.

Two Ways to Measure

So how is BC determined? There are several ways to approximate BC through predictive calculations, but we will focus on the direct experimental measurement of BC.

Measuring BC requires equipment and precision beyond the means of most shooters, but the process is simple to grasp. Fire the bullet and measure its muzzle velocity and one of the following:

A) Time of flight to some distance, or

B) Retained velocity

BC can be determined from either one of these measurements. The choice of which method to use depends on which instrumentation is available.

At the high end, there’s Doppler Radar, which tracks the bullet along each foot of its trajectory and measures its position, velocity, and deceleration along the way. Unfortunately, this technology is expensive and out of reach even for most major commercial bullet companies.

Dual Chronographs

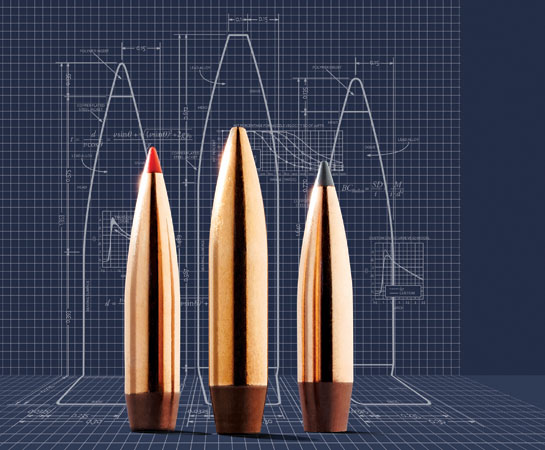

Photo by Yamil Sued

TIP: When using an optical chronograph, set it up at least 10 feet from the muzzle in order to get consistent readings. Fabric bags used for coffee beans and flour make economical sandbags, which can be used to keep your screens from blowing over on windy days.

A more conventional approach is to place a chronograph at the muzzle and another downrange. Firing a bullet through both chronographs will show you the bullet’s velocity decay directly. It’s simple, but there is a flaw with this approach. To get the most accurate BC measurement, you want to maximize the range between the two chronographs. Positioning them 100 yards apart is not adequate, and even 200 yards is marginal. You want at least 300 yards between the two chronographs. Supposing you have a range where you can do this, it leads to another problem. Careful shooters may be able to “thread the needle” from 300 yards a few times, but eventually the inevitable happens, and the chronograph takes a bullet for science. When that happens, the test is over.

The more practical way to measure BC over long range is to measure the time of flight using microphones that can detect the passage of the bullet from many feet away, allowing the sensor to be placed out of harm’s way. You still need a chronograph at the muzzle to measure the initial velocity. Also at the muzzle, a microphone will register the muzzle blast and trigger the clock to start. When the bullet passes the downrange microphone, the total time of flight is recorded. Along with the muzzle velocity measurement, an accurate BC can be calculated.

In principle, measuring BC is not difficult. The devil is in the details of measurement imprecision. Just one yard of error in range can introduce a 5 percent error in a BC measured over 300 yards. The same 5 percent measurement error can be induced by a 0.0014 second time-of-flight error, or a 4 fps velocity-measurement error. Precision while gathering the data is paramount.

After the raw measurements are made, the BC is corrected for standard sea level atmospheric conditions so it can be used as a basis for performance comparison and accurate trajectory calculations.

BC in turn forms the foundation for accurately calculating long-range shots.