“Shoot that buck!”

Apparently, I answered back, “I will.” I don’t remember saying any such thing to Justin, my new friend and backcountry hunting companion. My sole focus was the reticle of my scope dancing around the animal as I struggled to control my runaway breath and pounding heart.

He had spotted the deer, which stood stoically 200 yards away at the edge of a meadow, seemingly daring us to do something. It must have felt like an eternity waiting for the deep crack of my .270 Winchester. The deer continued to stand there, still and strong. I continued to sit there, focused but fitful.

Finally, my index finger moved a fraction of an inch. The mountains reverberated with the finale. Then everything was silent.

The sudden climax of the shot, the chiaroscuro of life and latent death, the golden grass sparkling with sunlight, the sharp funk of gunpowder and wet earth, and the final emphatic stillness all captured me. This was only the second deer I had ever shot at, and the first on public land. The moment transported me somewhere else. But a flashing, intrusive thought snapped me back to reality: “You need to work the bolt, get your eye in the scope, and get on that deer, now.”

I jerked out the spent shell and slammed in a new one while scanning for the deer. I couldn’t find it.

I turned back to Justin. “Did I hit it?”

“I didn’t see it run off. I think it’s down,” he said. After taking some time to collect myself, and my gear—which was scattered across the hillside—we set off across the meadow to find out.

Prior to our hunt I had known Justin for all of 5 minutes. He had dropped off some frozen bluefin tuna our mutual friend in San Diego, had caught and sent up with Justin. We chatted a bit about fishing and hunting and living in LA. A few weeks later, I got a text out of nowhere from a number I didn’t recognize. It was Justin.

“Hey Eric! Were you game to get out to deer hunt? I’m heading out this weekend and wanted to see if you wanted to get out with me.”

Yes. Yes, I did. I wasn’t even paying attention to deer season. I was dealing with work and a newborn son and a 3-year-old daughter and a wife and a Brittany that hadn’t been out to chase quail yet this season. I had been on some sort of pandemic lockdown or another for over half a year when I got the invite. Some time out in the woods sounded like exactly what I needed. But he sent that text Wednesday night and planned to hike into the national forest Thursday afternoon and stay the weekend. I couldn’t make that quick a turnaround.

I told my wife about the invite anyway, and she said if I left Friday afternoon she would make it work. So Justin and I hatched a hasty plan to meet up at a particular spot in the forest on Friday night. That would take me on an eight-mile hike in as dusk approached—first down a gated road and then a rough backcountry trail.

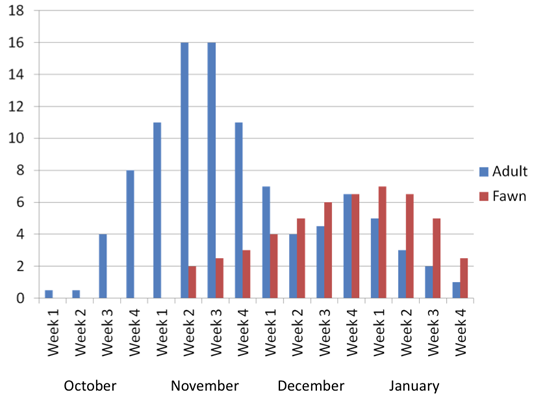

We were heading into D13, a general hunt zone with plenty of over-the-counter tags and lots of public land. But the zone has a hunter success rate hovering around 11 percent. Justin had already been pounding the ground for the past three weeks without seeing a legal buck.

Unexpected Success

As I started down the concrete road Friday afternoon, later than I had wanted due to a stop for my tag, some food, and a visit to the range to make sure my rifle was still sighted in, I hoped our hasty arrangement would work out.

I needn’t have worried. Just a mile or so down the trail I spotted a person with a heavy backpack walking toward me. I wasn’t sure at first, but the long dark hair, thin frame, strong beard, and kind eyes seemed like the guy who dropped off the fish a few weeks ago. My arms turned up in a “what’s going on?” gesture.

“I got one.”

I was excited for him. Every deer taken on public land in Southern California is a trophy, and he had gotten it done in less than a day on this hunt. I was disappointed, too, anxious that my hunt was over before it had even started. We chatted for a bit about what to do. There was talk of me going in solo, but I decided I wasn’t up for exploring this new country alone, especially so late in the day.

“I’ll just call it and head back,” I told him. “My wife will be happy to see me.” I think he could see through my attempt at being easy going. He knew I needed him for this hunt. I hadn’t earned it the way he had.

As we debated, a crowd of hunters on mountain bikes road by. We smiled and waved. Then a stream of cars poured in past the locked gate, heading to private property up the road. There were a lot of hunters here for the final weekend of the season.

We talked about going somewhere else, a spot we independently both knew reasonably well that we could drive into to save some time and Justin’s legs, which were burning from his pack out. But it was at 7,000 feet, weather was moving in, and neither of us had packed for that situation. Plus, given the spot’s accessibility, it too was likely full of hunters.

In the end, Justin volunteered to come back in with me. I did an about-face and we hiked back to his truck and made the short drive to town for some ice to keep his deer safe before we walked back into the wilderness.

I imagine in many parts of the country there would be nothing strange about pulling out a deer carcass in the parking lot of a gas station and sticking it in a cooler, but it felt pretty funny doing it so close to LA.

Plan B

By the time we got back to the trailhead the sun was setting. We toasted with some warm IPAs to celebrate Justin’s accomplishment and then set off in the dark, planning to get a couple miles in before setting up camp.

As we walked, we could feel the rolling hills, which had been so open and expansive during the day, closing in on us. “It’s amazing how claustrophobic everything feels at night,” Justin said. The landscape at once felt infinitely distant and oppressively on top of us.

Later we walked past a group camping in a turnout with an illegal fire blazing. We exchanged hunting pleasantries and they invited us to share camp with them. Normally the thought of bullshitting with strangers while sharing some beers and whiskey would be appealing, but I was here for a reason, and fighting a hangover while trying to rouse myself at 4 a.m. wasn’t going to help me shoot a deer. We politely declined and kept walking, hoping to put some distance between us and them.

But with the hour getting late and Justin’s legs all but shot, we decided to cut back on our original goal for the night and camp in a canyon Justin had heard someone had taken a buck out of. We scrambled down a nasty, steep, sandy game trail, crossed a dry riverbed, set up our tents, ate some chili mac, and turned in.

Before I could even unzip my sleeping bag, Justin was snoring the snore of a man who had put in an honest day of hunting and had filled his tag. Sticking some ear plugs into my ears to muffle the sound, I could only hope for the same in the coming days.

We woke early to rain, which dampened my hopes of seeing deer. The plan was to climb a finger a couple hundred yards away we had identified on our digital map, and then glass the canyon floor that led to a valley with water.

As we approached, turning our headlamp beams to high, we realized that the finger was much steeper and brushier than we thought it would be. There was no way up. We had to change tactics before sunrise.

After huddling over our phones we decided to cross the canyon and perch ourselves on a hill on the other side. The drizzle continued on and off. We found a spot that seemed to offer reasonable views of potential bedding and feeding areas, and settled in as best we could, slowly getting drenched. Justin must be kicking himself for coming, I thought.

Unfortunately, the only action we got that morning was of the human variety. In the distance we saw the headlights of even more vehicles drive up the road we had been walking the night before, and then the roar of an ATV driving up our canyon right at the start of shooting light. So much for seeing deer, I thought.

At one point I thought I heard a gunshot from the ATV crowd deep down the canyon. An hour later, a group of four other hunters meandered up the canyon the same way the ATV had gone.

READ NEXT: Best Public-Land Hunting Near Big Cities

There is something discouraging about seeing other hunters, let alone lots of other hunters, when you’re in the field. It’s the competition, of course, but also facing up to the idea that the plan you hatched was not nearly as original or clever as you thought.

The rain started again, harder than it had been all morning. Then it started hailing. We looked at each other, slightly miserably, and decided we needed to move. We had to get deeper.

A couple miles later we were walking past private property that somehow existed in the forest and saw almost a dozen does that seemed mostly unafraid of us. A mile or so later we passed another stretch of private land and Justin recounted the incident he had on an earlier visit to the area with the ornery landowner—who, rifle in hand—quizzed Justin aggressively about whether he was “poaching on my land.” We hurried through, thankful no one was around today.

Seeing a lovely draw up a hill that proved to be public land, we decided to take a detour and scope it out, only to find ourselves bushwhacking through dense willows and chaparral that slapped us and cut us and left us crashing and stumbling through a riverbed. Chastened physically and mentally from the ordeal, we climbed the hill and sat a while.

We saw no deer, of course, and had to return the same way, losing precious hours in the process.

We trekked down a narrow canyon, following a stream. A deer appeared on the opposite hillside and I struggled to bring my gun around while Justin pointed frantically, only for us to both realize it was just a doe and fawn, which quickly bounded away. Unlike the deer on private property, these critters were plenty spooky.

Improbable Success

We marched through an epic canyon, rock-hopping ungracefully with our backpacks on before reaching the spot where we had originally planned to meet up, which was situated at the edge of a meadow. We continued on to our hunting destination, a large bowl surrounded by dense draws filled with brush. It looked like a place bucks might frequent.

“I don’t know how we are going to get down there,” I said to Justin. Dusk was approaching and I was feeling worn down from our detour up the hill. I couldn’t handle another date with a bunch of sadistic brush. “We won’t make it before we run out of light. I think we should go back to the meadow.”

We set up just off the trail looking down on oaks and pockets of open land, and it might have been promising. But just a few minutes into our sit, Justin suggested we move.

“I think we’ll have a better view from the other side,” he said.

We didn’t have the best view, it was true, but I felt unsure about moving again with so little light left. Something told me I should trust him, though, so I agreed.

We marched around and located a hillside bisected by game trails with plenty of signs of deer and sat right down on them. We now had an unobstructed view across the meadow and a limited look into the oaks. It didn’t take long to see something.

“There’s a deer!” I whispered-yelled. I spotted what I was sure was a buck just inside the dark tree line a couple hundred yards away, but I couldn’t tell if he had a forked horn—the legal requirement in California. I thought about trying to put on a stalk to get closer, approaching with the cover of some large bushes in the meadow. All I had were these 30 minutes and a morning hunt left, and there was a deer, right now, in the trees. But Justin suggested we hang back.

“We know there are deer here,” he said. “We should come back in the morning.”

I knew he was right. My potential stalk had a good chance of spooking the deer, which would leave us with no options. Hopefully that buck would come back tomorrow. We watched him mill about in the blue light until the shooting time ended. Finally, we went our way, and the deer went his.

Things felt different the next morning. It was the last day of the season. We had seen what was almost certainly a buck. And the weather had taken a turn. It was no longer wet, but clear and very cold. I woke up chilly and sore, with ice crusting my tent and cramps roiling my legs and shoulders. Still, a cautious optimism that bordered on excitement dragged me out of bed and forced me into my crispy boots.

Justin was not quite of the same mindset. After all, he was tucked in a warm sleeping bag and had a deer waiting for him in a cooler back at his truck. Nonetheless, he emerged from his warm den to help me, sleeping bag in tow, and wrapped himself in it once we hit our spot. I shivered in the clean cold air, eyes glued to my binoculars.

I saw things. Many of those things I thought were deer. Filled with exhaustion and hope, any perceived movement in the monotone pre-dawn light was enough to stir me. What 20 minutes later would prove to be bare tree branches twisting in the wind looked like the rack of a giant buck just inside the dark oaks. What seemed like a fawn perusing the meadow turned out to be a jackrabbit.

I enthusiastically relayed each sighting to Justin. At first he must have thought that we had hit a honey hole so filled with cervids that it was going to be like one of those Big Buck Hunter arcade games once the clock ticked over to legal light. Only after dawn broke and I realized my errors did I slowly and half-heartedly start to report that maybe some of the things I had mentioned weren’t actually deer.

But then I did see a deer. A little spike popped out of the oak trees and began grazing toward us, trotting his way diagonally across the meadow. He definitely wasn’t legal, but I was also sure the deer I had seen the day before had taller antlers than this guy. Maybe that buck was still out there.

Finally, we saw some activity behind the oaks. As I followed what I thought might have been my spike and contemplated moving in, Justin whispered, “There’s one!”

It took me a few moments to get eyes on him, but once I did I immediately knew that it was a shooter. And by that I meant it looked like a legit 2×2. The deer seemed to be nosing a doe, following her around behind the cover of oak trees. He moved back and forth with her, driven by his rutting instincts, but was too deep in the trees for me to have any chance at a shot.

I began peeling off layers in preparation for a stalk, hoping to get an angle on the buck, but I must have made a racket because he broke off from his paramour to walk out into the meadow a few steps, confronting us from across the field.

I sat down and Justin tossed me his shooting stick. At some point, I pulled the trigger.

First Deer

We made our way across the meadow, orienting ourselves to a small bush the deer had been standing by. When we got to the spot where I thought I shot the deer I saw nothing. Panic started to set in, and I began looking frantically for any signs of a hit. Then Justin called out, “Over here!”

And there it was, laying down behind another bush maybe 15 yards from where I had shot him. The buck was even nicer than I had thought, with three points on either side of his rack. I had killed my first backcountry deer.

When I walked up on him, I saw a hole halfway back on his body, bloody and leaking clumps of grassy matter. Turning him over, I saw the shot had entered pretty much where I had aimed, right behind the front shoulder. That part was good.

But I had gut shot it. When I took the shot I had thought the buck was standing basically broadside with just his head turned in our direction, but obviously he had been quartering towards me quite a bit. Because of the angle, the bullet had exited farther back. After gutting the animal (with Justin’s steadfast assistance, including spelling me for a bit when I started gagging from the goopy soup of innards left by the 130-grain copper bullet that had passed through) we discovered that I had hit the liver and a bit of one lung. I felt lucky that was enough to bring him down quickly. I kicked myself for the shot placement.

We worked together to break him down, laying the quarters and backstraps on a nearby tree as we went. Slowly, the deer changed from creature into meat in that strange transmogrification that only hunters and maybe old-school butchers understand. In the end all that was left was a gut pile, clean ribs, and a backbone.

By the time we got the meat back to camp and packed up, it was well past noon. Mercifully, Justin took half the load, and as I slung on my backpack, I said, “This doesn’t seem so bad.”

What a stupid thing to say. Fifteen minutes down the trail, I was hating life. My hips rubbed on the waist strap and ached from the load. My back strained and my shoulders felt the sagging weight bear down on them.

Hours later we took a break and momentarily shed our packs in the gathering darkness. Justin had his pack off first and said, “I feel like I’m on all the drugs!” I took mine off too, took a couple steps, and laughed. Conditioned by miles spent with such a heavy load, once we ditched our packs the mind was unable to control the body and our legs disappeared, wobbling and swaying, detached the brain’s insistent orders. We weaved and floated like we were walking on the moon after a night of partying. And then we put our packs back on and all the hurt, unfortunately, returned.

It was fully dark as we worked our way down the concrete path, my trekking poles clicking annoyingly each step of the way. We saw a car’s light in the distance, and I felt lighter for a second. We must be almost back.

Justin, who had walked this trail many times in the past month, said we still had a way to go. “Damn,” I thought. Every step was an agonizing event. Justin was just messing with me. A few minutes later, we were at our vehicles. Given everything we had gone through, I didn’t mind the joke.

We dropped our packs and then, ignoring all COVID protocols, hugged each other tight. Two deer in three days on Southern California public land was a major accomplishment.

But the embrace was more than a testament to our success. It was the recognition of an experience and powerful bond that can only form when people camp together, work together, are tested together, suffer together. Hunt together.