IT IS DIFFICULT, if unwise, to talk about the history of Outdoor Life without talking about Jack O’Connor. He sold his first story to the magazine in 1934; two years later, he had secured a one-year contract to write 18 Outdoor Life articles for $2,700. (That’s roughly the equivalent of $58,000 today.) By the time he retired from the magazine, in 1972, he had written some 1,200 articles. These are a handful of the images—published and excluded as outtakes—from those stories.

With hundreds of our old shooting editor’s* adventures and columns to sort through, it’s challenging to piece together each photo’s precise context. This collection of original JOC photographs has been filed in our archives for decades, only seeing the light when we need art for an anniversary celebration or a sheep story. The few details scrawled on the backs in grease pencil are often illegible—a year here, a location there. Mostly, they’re just stamped “Outdoor Life.”

While you may not have seen many of these photos before, dedicated O’Connor fans have almost certainly read about the hunts behind them. As O’Connor’s son Bradwell once pointed out, “Dad’s hunts—all of them, even his afternoon sashays from home or office into the Arizona desert for quail and jackrabbits or in later years for upland birds or rock chucks in Idaho—sooner or later showed up in his writings.” Even without the specifics, the images remain valuable in their own right. They capture O’Connor’s confidence and expertise, his aloofness and relatability. Most of all they reflect a singular era in hunting history, and the hunter who helped define it.

*O’Connor’s titles on the masthead include arms and ammunition editor, gun editor, shooting editor, and hunting editor.

Jack O’Connor in Africa

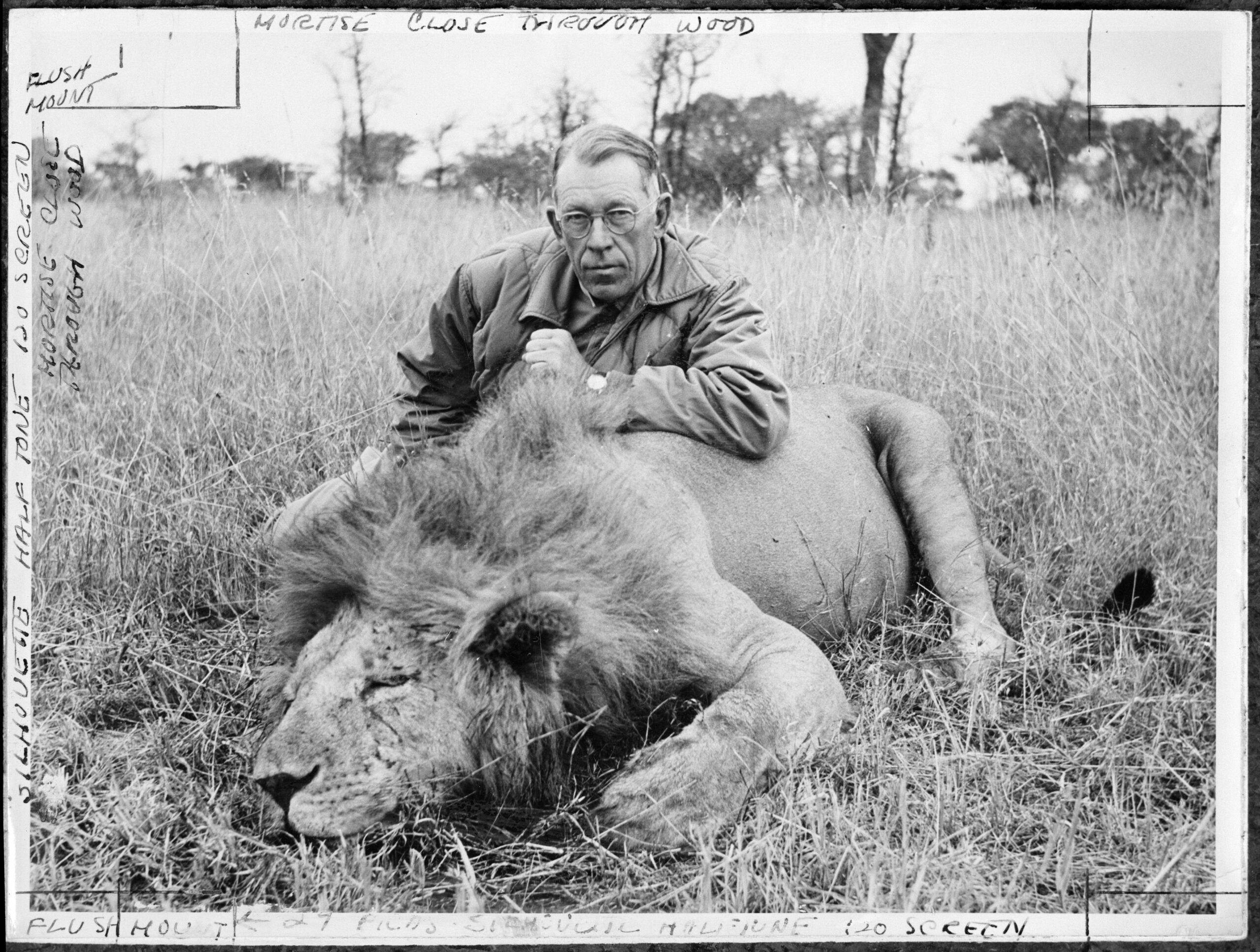

O’CONNOR FIRST went on safari in the summer of 1953, spending more than three months in Kenya and what is now Tanzania. Outdoor Life was the first outdoor magazine to send its shooting editor on safari, according to former editor-in-chief Bill E. Rae. While O’Connor would go on to write 15 stories based on that trip, the first was about his hunt for the lion pictured above. That story ran in the November 1953 issue; that photo did not. O’Connor was known for writing about his missed shots (a practice among outdoor writers that remains less common than the misses), and he did so in “Lions Don’t Come Easy.”

“As we sneaked back to the car I was about as low as I have been in all my life,” he wrote. “I had dreamed for 40 years of killing a great-maned lion. Two of them had been tossed into my lap—and I had flubbed the opportunity like an excited schoolboy missing his first buck.”

O’Connor later discovered his riflescope had rattled loose. He eventually killed his first lion with his Model 70 in .375 Magnum. “As the 71.5 grains of No. 4064 powder exploded and drove the 270-grain soft-point bullet into the great cat’s neck,” he wrote, “all hell broke loose.”

“His great sandy body was as smooth and round as a sausage,” he wrote of the big cat. “His blond mane was heavy, shaggy, long. Don Ker told me he probably weighed 500 pounds, and was one of the largest lions he had seen in 27 years as a white hunter. From the tip of his nose to the last joint of his tail he was nine feet seven inches long as he lay there. All in all, he was some lion, and of all the trophies I have taken, the only one that has given me a greater thrill was the first desert ram I stood over, almost a quarter of a century earlier and a half a world away.”

ALTHOUGH O’CONNOR killed an eland on that first safari (he got distracted by a good bull while hunting lions), the one pictured here is from a later trip with his wife, Eleanor. This color photograph of O’Connor kneeling beside a record-book eland has been picked up by many publications to accompany general articles about JOC. Not, I suspect, because most readers know a good eland when they see one (such stories never actually mention his eland hunts), but because it’s such a good portrait. Quality color images of the shooting editor at this age are hard to come by, and this is an excellent one of both the hunter and his .375 Magnum. It originally ran in the August 1961 story “Big as an Ox.” The zebra photograph below ran in the same story.

“Our party was one of the last to hunt the Simiyu country; not long after we pulled out it was made part of the Serengeti National Park,” O’Connor wrote in 1961. “But what a hunting country it was when we were there!”

Jack O’Connor in North America

WHILE HIS TRAVELS took him all over the world, O’Connor was best known for his adventures in the Southwest and, of course, sheep hunting.

“This is the account of a hunt for white-tails in a region, where, according to the authorities, no white-tails live,” O’Connor wrote about Mexican Coues deer in the January 1939 story, “What, No White-Tails?” “Maps of their distribution show the whole coastal desert of the Mexican state of Sonora is void of them. Actually, I have seen them there by the hundreds. I told a scientist that once, but he raised his eyebrows, and pulled out a distribution map to show me. I was wrong, he was right—the book said so. Further, he told me, the white-tail could not exist without open water. So again I was wrong. Hence the trip about which I am writing. When I went into Sonora in the fall of 1937, I wanted to bring back a whole family of desert white-tails for the Arizona State Museum, so my skeptical scientist friend could see them.”

O’Connor wrote about another Sonoran hunt in the May 1941 story, “Sonora Luck—Mixed.” This time he was hunting for desert mule deer while based out of La Primavera, a “typical desert ranch, with a big adobe house, where the foreman, his family, and his son-in-law lived.”

BIG GAME OCCUPIED many of O’Connor’s stories, but he was a devout bird hunter who wrote often about Gambel’s quail in particular. The portrait above is an unused image from a 1939 story where he and Eleanor lucked into coveys without doing much work at all.

“I’ve been hunting birds and big game ever since I could follow my father and grandfather afield,” he wrote. “I’ve seen many strange things—mountain sheep on the flats, a swimming wildcat, a big buck that chased me—but those self-driven quail topped anything I’ve encountered in thirty years of hunting.”

As many longtime readers know, O’Connor often hunted with his wife, Eleanor, and she appeared frequently in his stories. They met at a mixer while attending the University of Missouri (where O’Connor was earning a graduate degree in journalism) and eloped in 1927. Jim Casada writes in The Lost Classics of Jack O’Connor that because O’Connor lost his hunting mentor at the age of 13, when his grandfather died, he was particularly passionate about taking others hunting.

“…The sporting deprivations of his later adolescent years influenced Jack a great deal, because once he had a family of his own, he consistently made a point of sharing his hunting experiences with them … Jack shared his passion for hunting with Eleanor and took great pride in her marksmanship, and in each and every one of the many sporting milestones attained by his family.”

In the same book, Bradford O’Connor also notes his father’s marksmanship (and fondness for bird hunting), which endured to his final days: “On our last upland hunt together a few months before Dad’s death in 1978, a big pheasant rooster flushed from a clump of brush about 50 yards away. I didn’t shoot, but Dad shouldered his 28-gauge Arizaga, said, ‘Well, hell,’ and fired, dropping the bird. We stepped off 70 yards. The rooster was hit by a single No. 6 pellet in the head.”

ONE OF O’CONNOR’S lasting contributions to hunting are his sheep stories. You can read many of those original stories in back issues and Outdoor Life treasuries, but his thoughts on the subject are collected in Sheep and Sheep Hunting. In the foreword, he wrote:

“I do not think that there is any doubt but that a large old ram of any North American sheep species carries more prestige than any other. The good ram is relatively rare, and securing one requires hard work, judgment, and self-control. Many an Alaskan brown bear has been shot by fat old men with emphysema and fallen arches after a short stalk along a level beach. Many a grizzly has been collected when he has come to dine on a dead horse used for bait. Those great cats, the lion and the tiger, have been baited and driven and shot by old men who wouldn’t walk a mile if their lives depended on it. But the wild ram is found in high and generally rough country. Sometimes ram country is so high and so rough that the hunting is dangerous. I have come close to breaking my neck in the low but very rough mountains of Sonora, and once in Iran I took a tumble and broke and cracked a half-dozen ribs. Hunting at 11,000 feet in Wyoming, I once made a scramble up a steep ridge that left me so short of wind that for a moment I wondered if I was having a heart attack.”

O’Connor credited much of his sheep hunting success to his “more than average experience” and to the fact that he “began sheep hunting long before sheep hunting became fashionable.”

“He fretted over his role in creating a Grand Slam hysteria,” Bradford O’Connor once wrote. “He is said to have been the fifth person to bag all four varieties of North American wild sheep, and he blamed a new breed of affluent and highly mobile hunter for turning the Grand Slam into a status symbol. He said too many Grand Slam seekers were so driven by greed and ego that they cared little about the sights, sounds, and smells of sheep country.”

By the end of his own hunting career, O’Connor had completed two sheep Grand Slams. “If I’ve learned one thing in 40 years of seeking the majestic wild ram,” he wrote in 1971, “it is that hunting him is not a privilege to be taken lightly.”

Read stories from the Outdoor Life archives:

- An Ontario Moose Hunt Turns Into a 10-Day Survival Ordeal, From the Archives

- Arrow for a Grizzly: A Classic Fred Bear Tale from the Archives

- My Lady Judas: The Wolf-Dog That Called In a Pack of Wolves for Frank Glaser

Or check out more OL+ stories.