In January, Utah Representative Jason Chaffetz introduced a bill that would eliminate the jobs of U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management rangers. The idea behind the bill is that local law enforcement could do a better job policing than the feds. The sentiment that federal agencies are overreaching their responsibilities on massive tracts of public land in the West played out in a dramatic standoff the previous year when an armed militia seized the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon and demanded the federal government relinquish control of the 187,000-acre refuge.

Chaffetz’s bill and the Malheur takeover captured national media attention, painting a picture of stark conflict between local westerners and federal land managers.

But as Tim Love tells it, this sort of heated contention is the exception, not the rule.

Love was the U.S. Forest Service district ranger for the Seeley Lake area of the Lolo National Forest in northwestern Montana for 20 years. He was in charge of managing 400,000 acres for outdoor recreation, wildfire management, wildlife habitat, and timber harvest until he retired in November 2014. Because he is retired, Love can speak freely about the Forest Service.

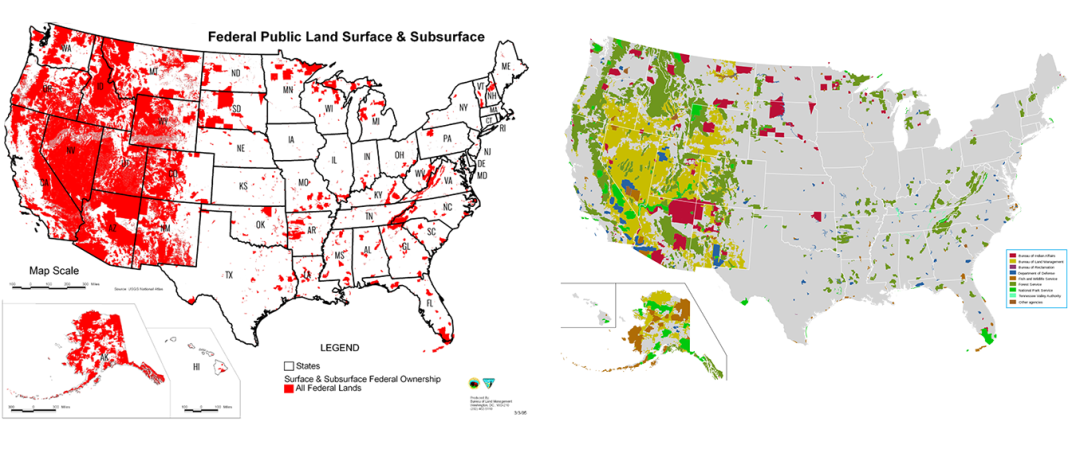

Love admits there are real problems facing federal land and challenges for those trying to manage it. But according to Love, the solutions to those problems include simplifying regulations and working closely with the community—not extreme measures like transferring lands to the states or stripping away agency budgets. We interviewed Love to get his perspective on what it takes to be a good land manager and how the federal government and the public might find some compromise on 640 million acres of America’s federally managed ground.

Outdoor Life: Did you work closely with state agencies as a district ranger?

Tim Love: I worked closely with Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks—which is in charge of managing the wildlife in the state. They were located in our ranger station. The state’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation had its own station about 16 miles away and we worked with them a lot on access and fire management.

OL: So there’s sentiment that state agencies can do a better job managing land than the feds because state agencies are on the ground with the public. But in your district, you and the state agency were in the same building?

TL: That’s right. So let me say this: That sentiment does exist, but it’s not as prevalent in Montana as it is in Idaho or Utah where there’s a lot of livestock grazing on BLM land. I like to think we do have a good relationship with the public. My experiences have always been positive.

OL: Why do you think that’s the case?

TL: Some of it has to do with local culture and how the community relates to the ranger and his staff. When I was in college I had a policy professor who told us: “Rangers are not a delegate from the community to the government. You’re supposed to be an emissary for the government.” But in my experience, really, you’re both. You reflect the values of the community and their interest in the national forest. But we work for the federal government, so we have to protect its interests, too. Because we work for the government, we really are public servants, we’re not public masters. I grew up in Montana, so I know the area and the culture. I camped on the district when I was an elementary school kid—

OL: Wait, so you’re not a suit-wearing operative from D.C.?

TL: No. My roots and values are here. That’s not to say you can’t come from New York and be an excellent ranger. It’s more about how you were brought up and how you relate to the land and relate to the people.

OL: How can outdoorsmen and women be more involved in management decisions?

TL: When local sporting groups can get together, have a sit-down meeting with the district ranger, and talk about their interests or concerns, that can be very effective. When you have public support from a variety of different groups on an initiative, even judges will take that into consideration. So for any given project, it takes input from a lot of different people and then we can modify plans accordingly.

OL: How can agencies do a better job of relating to outdoorsmen and women?

TL: The public doesn’t want to follow some sort of perfunctory process where they’re going through the motions. They want to have a real conversation, not somebody just checking off comments. The people have to feel that what they are saying is being considered. As a district manager, you have to go farther than the law [National Environmental Policy Act] requires on the public input process.

OL: What are a public land manager’s biggest challenges?

TL: Oh boy. There are always funding issues, but that’s the world we live in. More recently, fire funding has become a really big issue. When I started, fire funding [for wildfire fighting and management] was no more than 20 percent of the budget. Today, it’s more than 50 percent of the budget. So all the other programs have to be reduced because that money is going to fire relief. Fires have gotten a lot more intense and frequent.

OL: How much does your job change with the election cycle?

TL: It can change a lot. Typically, a new administration comes on board and they enact a hiring freeze. Funding varies a lot by administration because the U.S. Forest Service is a discretionary funding source. But one of the biggest problems is we get our budgets so late in the year. It takes a lot of time for the budget to get proposed, work through Congress, then go to the agency, and finally work its way down to the districts. We’ve gotten our budget as late as March. But the end of the fiscal year is September. So from October to March we’re treading water.

OL: There’s a lot of rhetoric about “locked up” federal land. In your opinion, are federal lands being used effectively for multiple uses?

TL: I’ve worked on grasslands, I’ve worked in the eastern edge of the Rockies, and here in the Lolo. I’d say in general there is good multiple use of our national forests and there has been since its inception. Now, what’s changed? There’s been a host of environmental laws through the 60s and 70s and into the 80s (National Forest Management Act, Environmental Policy Act, Endangered Species Act, The Clean Water Act). So, I think more of the restrictions that people actually feel come from regulations that originate from those laws. Now, all of those laws are good and well intentioned. And we have all the same activities going on that we always did, but there’s more regulation on those activities. So people do feel a little squeezed.

OL: If you could make one overarching change to how federal lands are managed, what would it be?

TL: I think there needs to be tort reform. Where I worked in the northern Rockies, there are groups that are empowered by conflict. That’s their interest. They’re mercenaries. They have a different vision of how a national forest should be managed. Some don’t want any trees harvested commercially, period. Or they want timber harvest done in such a confined way that it won’t meet management objectives. I would like to see some sort of alternative dispute resolution for dealing with groups that want to fight and litigate rather than work together. I’m not against litigation. The public has a right to air grievances to its government. But in some instances these rights are being abused.

OL: What would happen if BLM lands and Forest Service lands were transferred to the states?

TL: Here’s the issue: the state would inherit the same laws and regulations we have to follow. So they would have to manage accordingly. The state does not have the budget to manage the resources the way the Forest Service or BLM does. So that would be a huge burden to find the funding at the state level. Are the states capable? Indeed. They have wonderful foresters and staff. It’s not that. It’s having the budget to manage the resources and deal with the complexities of the laws.

OL: Why do you think the push to transfer lands to the states has cropped up again?

TL: It’s been resurrected several times. It was strong during the Regan administration as the Sagebrush Rebellion. Now I’ve got to just share my observation about that Bundy situation. Here’s a guy who has been grazing his cattle on public lands for a long time. And the rate of payment is so far below the market average for what he’d have to pay a private landowner for grazing. Here’s a guy who is essentially on public welfare, and he’s the one grousing about the federal government and people on welfare. I get annoyed by people who denigrate the government and at the same time benefit from the government. It’s all self-interest. He wants the land for free. But guys [like Bundy] fuel anti-government attitudes. And when people feel over-regulated, they can more easily become detached from their government.