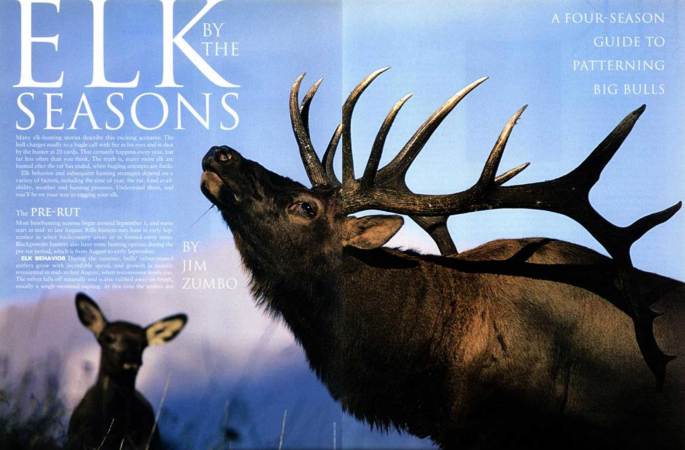

For more than 100 years, wildlife authorities have tried to shore up the elk population close to Yellowstone National Park with supplemental feeding at the National Elk Refuge near Jackson, Wyoming.

But the steady creep of Chronic Wasting Disease has forced the refuge managers to reconsider this tradition. That’s troubling for those who fear major losses to the herd. Others say changes are needed to dodge even greater disease issues.

First, some history. Yellowstone was one of the few places where elk survived overhunting in the 1800s. However, Yellowstone is a high plateau where elk cannot survive through snowy winters.

Historically, elk migrated to valleys, like Jackson Hole. However, as settlers brought in cattle, hungry elk clashed with ranchers’ pastures and hay supplies. Development of Jackson Hole as a resort town ate up more habitat. In 1912, the federal government set up the 24,700-acre National Elk Refuge (six miles long and 10 miles wide). Yellowstone elk provided much of the seed stock that successfully restored elk around the western United States over the 20th century.

Now, thousands of elk descend on the National Elk Refuge each winter, treated with feed once they arrive. Exactly how many arrive, and how long they stay, depends on the snowpack and the condition of surrounding forage. Humans also enjoy viewing the elk and winter sleigh rides there are an established attraction.

Enter into this, the highly contagious and fatal CWD. Concerns over CWD upped pressure on the USFWS to reduce concentrations of elk.

USFWS released a “step down” plan.

The agency’s goal is to have 5,000 elk wintering on the refuge. The plan says that there are about 11,000 elk in the Jackson herd, of which 6,000 to 7,000 winter on the refuge. The agency says they aim to reduce the number of elk on the refuge, but not reduce the Jackson herd overall. It aims to do this by shortening the feeding season, starting in 2020, eventually phasing it out.

Wyoming blogger Todd Helms came out against the plan: “Pressure for this misguided and dangerous action plan is being placed on the federal government by environmental activist groups who are using CWD as a fear-mongering tactic to eliminate the program,” he wrote.

Helms worries elk will starve without the supplemental feed, and that fears of CWD are overblown.

Read Next: Can CWD Really Be Cured?

But it’s not only environmental groups that have expressed concern about the supplemental feeding program. In 2017, the Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Commission asked the state of Wyoming to phase out the feeding program.

“As a commission, we believe that we cannot successfully address CWD without Wyoming’s help,” Montana commissioners wrote. “As your neighbor, we ask you to begin the process of closing these feed grounds.

CWD has been found in mule deer near the refuge, but not Refuge elk…yet. CWD infects members of the deer family, particularly elk, mule deer, whitetail deer and moose. It is spread by proteins shed by infected animals that can linger in soil or be spread by contact between animals.