Willow Creek is nowhere. It’s one of countless unremarkable prairie streams too small and intermittent to float a boat but too deep and changeable to cross easily. Even during dry seasons, getting across it requires finding a place where the sheer banks have sloughed away between pools of stagnant, fish-stranding water. Mule deer and cows cross here, and so do I, when I want to hunt the grassy coulees and crumbling badlands on the other side.

Willow Creek is everywhere. In Montana alone, dozens of Willow Creeks drain mountains and scour prairies. Most got their name because Beaver Creek was already taken, and also from the narrow-leafed shrub that holds their banks in thickets and tangles. Old-timers call it “coyote willow,” maybe because wherever it grows, its banks are tacky with drying mud stitched with the tracks of the wild dogs snaking in and out of its shadows to surprise a jackrabbit or pounce on a vole. Thin and limber as sugarcane, and spiked with tiny yellow flowers in the spring, coyote willow is ever a sapling, throwing scarcely enough shade to cool a panting cow. In the throbbing summer heat, willow groves smell like creosote below an old railroad.

In the fall, Willow Creek is everything. In a landscape defined by inch-high woolgrass and razoring winds, it’s a magnet for open-country mule deer that bed in its buckbrush bends and breed in leafless rattling thickets. In winter, sharptail grouse descend on streamside willows to tuck out of the wind alongside twitchy prairie cottontails.

Willow Creek could be anywhere. Except mine is right here, meandering drunkenly through my northeastern Montana homeland as it transports the slurried prairie, stacking 3 miles of ropy twists into every map mile as it makes its way to the Milk River.

For most of the year, my Willow Creek is nearly dry, and if it weren’t for stick-and-mud beaver dams around every other bend, I could walk its bed for miles, invisible to bucks on the adobe ridges above it. But for several weeks, Willow Creek swells and churns with runoff, a perilous boilage of cottonwood limbs, bloated calves, and, during an especially heavy flood a few years ago, rough-cut planks from a washed-out county bridge upstream.

Willow Creek never raises its voice, even during these unsettling deluges. There are no chattering rapids here. Instead, the creek’s gurgle deepens as it swallows gumbo banks and root wads in suctioning swirls. Its flow sometimes increases so silently and astonishingly that I’ve awakened to floodwater fingering across its mile-wide valley, an instant lake that reflects the sunrise with an intensity of light I associate with seashores and snowfields. In the spring, as snowmelt lifts and breaks ice into truck-size blocks, the creek mutters in the dark, tectonic plates of ice clocking and grinding their way downstream, flattening willows and scarring the trunks of streamside cottonwoods.

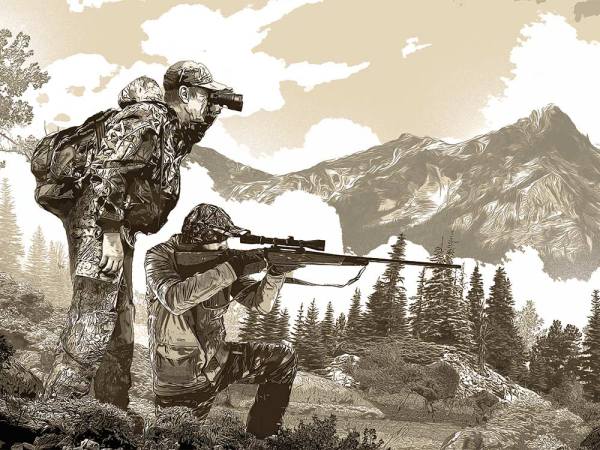

If it can rise overnight, Willow Creek takes days and even weeks to recede, like a friend holding a grudge. The valley—after the water returns to the steep-sided channel—is hard to cross, all sucking mud and shipwrecked trees in a prairie that is accustomed to being dry and treeless. In those seasons, Willow Creek cuts me off from most of our property, and I’m reduced to simply watching, through binoculars or spotting scopes, a parade of handsome bucks on the other side, killable but for the trench of hungry water between them and me.

Why do I care? There’s no shortage of deer or dry land elsewhere in my county. But those places don’t hold me in their sway, and a buck hunted on Antelope Creek or Bitter Creek somehow isn’t the same as a buck that shares my valley. So, I wait for the creek to dry into a bed of cracking mud and retrace steps I’ve made for 20 seasons, passing bends where my kids killed their first deer, where I can sometimes jump a wood duck on a tannic pool skimmed with spear-shaped yellow leaves, and where buffalo bones poke out of a cutbank.

It’s then that Willow Creek switches from antagonist to silent hunting partner. Mule deer that easily vault over barbed-wire fences don’t test the creek’s friable banks. Instead, they tuck into the willows, and if the wind is right and my approach is stealthy, I can often deliver an arrow or a bullet to deer that think they’re hidden by the pecker-pole screen of slender trees.

Later, when it freezes clean down to the earth, trapping carp and sucker minnows in blocks of clear ice, I walk Willow Creek with a shotgun. On days when the snow blows sideways, pheasants and grouse will be tucked into streamside cover, watching for danger from overland, not from below. Roosters rocket straight into the pewter sky, cackling with surprise and betrayal, then fall to the ice, their gaudy plumage the only color in a monochromatic day.

If I’m familiar with every bend and grove on Willow Creek as it wends through my place, upstream it’s a wilderness of hardpan flats and sage wastes, desolate tableland where even antelope don’t linger. It would take days of walking to reach its headlands, rimrock country that tips into the Missouri River Breaks. Along the way are remains of homesteads sunk into the gumbo like shattered boats on an ocean, the only evidence little shards of pottery and bed springs, and the occasional harrow, teeth rusted and blunted from trying to turn this thin-lipped prairie into field.

You see leavings and hear tales of people who lived here, gossip that becomes history after a hundred years. The remains of the German’s shack, wallpapered with bank notes from the Weimer Republic, when the pre–World War II inflation made his life’s savings worthless. What’s left of the homestead of a family that froze to death when they ran out of punky wood and cow pies and, finally, shingles to burn. The outlines of a grave dug in a hurry after an argument in town.

Overlooking the creek and the remnants of those temporary honyockers, I find circles of head-size stones that held the buffalo-hide skirts of Assiniboine tepees against the shouldering wind. Their campsites confirm that I’m only the most recent hunter to track deer into the willows.

Under the sprawling sky, this is a country of geometry. Above the valley and the tepee rings, it’s a grid of square-mile sections and linear horizons, plumb-straight fences and alternating strips of winter wheat and summer fallow, green and khaki stripes that march away in lock-step precision, like the herringbone pattern on an old quilt. Maybe this is why Willow Creek captivates me—it’s the only disobedient feature on a landscape that’s been tamed by township and section line and survey stake.

Read Next: The .25/20: A Favorite Deer Rifle, a Thanksgiving Gift

Unruly meanders are a dividend of flowing water, whether it’s a tasty trout riffle or the lazy reach of an inside catfish bend. On a live stream, every moment is distinct from the one just before it, or the one yet to come. The water that was just here, coursing over that rock or slipping under that bank, will never be here again, and will be different around every next bend. Whether you use that knowledge to catch a trout or time a leap or shoot a buck doesn’t much matter. It’s the unrepeatable moment that matters.

Across the West, including my corner of Montana, public agents and irrigation masters have an enduring affection for reservoirs. What greater gift could land reclaimers give to arid regions than consistent water?

But the bargain never seems square. Who hasn’t stood on the lifeless, baked-mud shore of a drawn-down Western reservoir and wondered at the alternative: a wild-eyed creek or cheerful river chewing its way through this valley, building sandbars and shoals in the easy years and swallowing outside bends in the take-back floods?

If dam builders only see Willow Creek at flood stage, its whorls lapping at bankside willows and gobbling up my real estate, it’s an easy argument to tame it. But then the water drops, and the streamside grass thickens calves and fattens fawns. Thrushes and meadowlarks and black-and-white kingbirds chatter and flit, and on hazy summer evenings, the hills soften to purple and gray. At the center of it all is the creek, obeying only the pull of gravity and distributing exactly as much life as it withdraws. This is the gift of moving water, if only we can receive it.