How to Bag the Biggest Buck of Your Life, by Larry Benoit, was a seminal tome for a generation of deer hunters. Originally published in 1974, the book chronicled the hunting strategies and tactics of a hardcore North Woods deer tracker. And just like its title, the contents are splendid in their simplicity. Benoit, who passed away in 2013, gained notoriety for his ability to snow-track huge Maine bucks.

“He was kind of like Babe Ruth for hunters,” said Boone and Crockett measurer and longtime friend Ron Boucher in a New York Times obituary. “He was probably known by more hunters than any other person for his time.”

The Ruthian comparison was apt. Now, meet Lou Gehrig.

Big Leagues

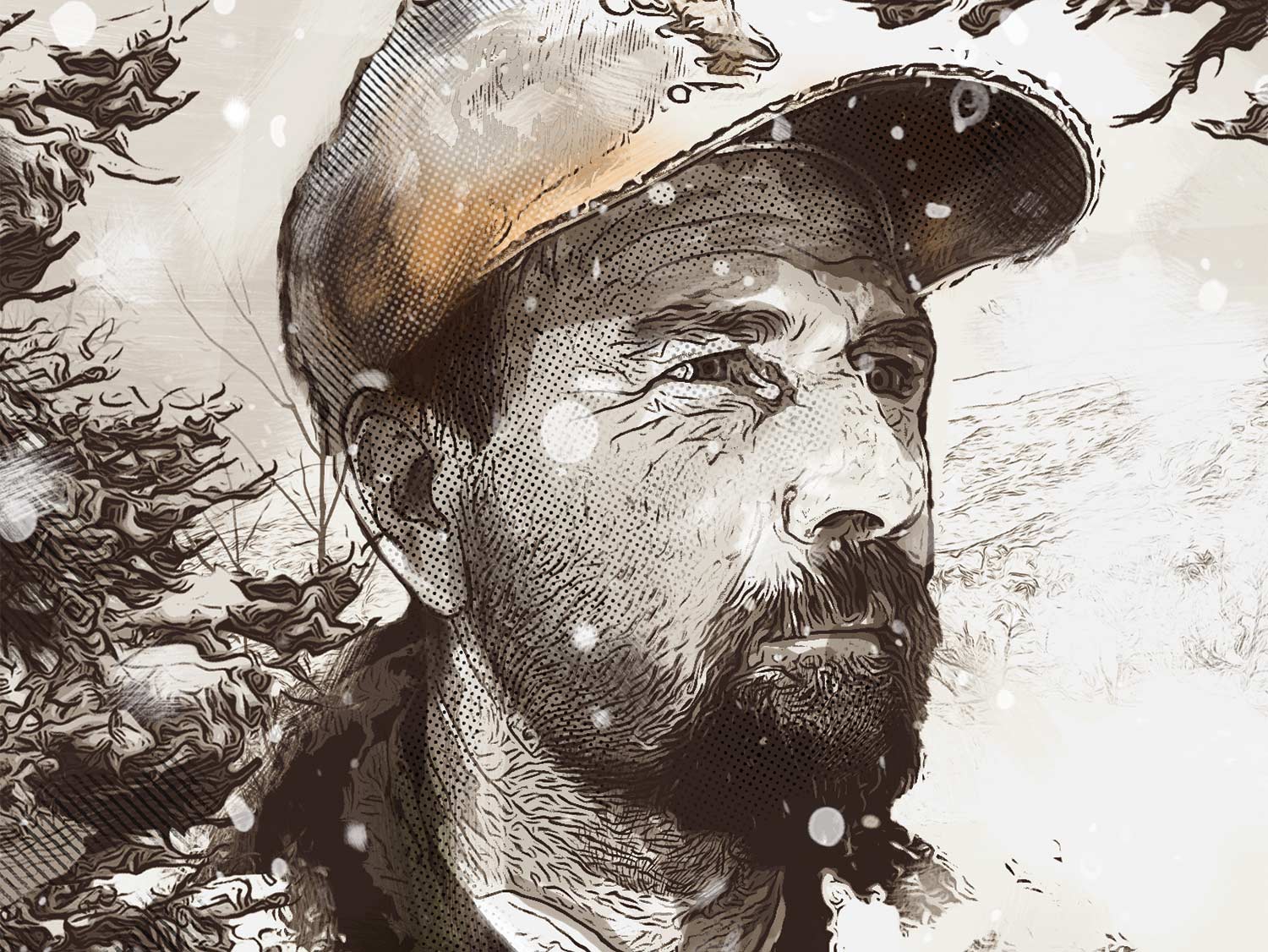

For the uninitiated, 62-year-old Hal Blood of Jackman, Maine, is a straight-talking Marine Corps veteran, former lobsterman, and deer-dogging savant who essentially picked up where Benoit left off.

He began hunting whitetails with his dad when he was just 10 years old and will admit—albeit grudgingly—to having taken north of 100 mature whitetail bucks in his life. Many, if not most, weighed more than 200 pounds, the iconic yardstick of Maine deer hunting.

But for Blood, the experience of taking a big-bodied buck in its element, tracked solo through the snow, is far more meaningful than any tally sheet could ever be. Although the lean and wiry hunter remains addicted to running down big bucks and is remarkably capable of outdistancing them (and many outdoorsmen half his age), he also relishes helping others these days.

“I like to teach hunters to track because I had to figure it out myself,” says Blood, who wants to pass on the tradition. “I hope to save people some of that learning curve.”

With in-the-field tracking schools, he spends much of his time helping sportsmen better understand what it takes to follow big bucks through the North Woods. In addition to his role as a Master Maine Guide and seminar speaker, Blood holds offseason tracking clinics designed to provide hunters from open country or densely populated areas with insight into the big woods.

“These deer that live here, well, they don’t have a timetable,” Blood says. “They don’t move from crop fields to bedding areas at any specific times of day like deer might do in farm country or in more suburban areas. They’re trying to find does—that’s it, nothing more. They might eat mushrooms, acorns, and beechnuts along the way, but they’re pretty much impossible to pattern. That’s why snow-tracking them is a very different strategy for most, but also the best tactic for shooting one. The anticipation of where and when you catch up to a buck is the mystique.”

Blood is adept at hitting curveballs—and mature whitetails can throw many varieties—especially on parcels of public land he’s never set foot on before. Improvisation, persistence, and patience are his watchwords, and they came in handy on a late-season hunt two years ago.

It was mid-December, and his original plan was to drive to Massachusetts. When snow conditions deteriorated into a crusty mess, Blood went to Plan B.

New Ground, New Deer

Indeed, during some seasons, perfect snow-tracking conditions never come to the North Woods. A lack of snow, of course, makes tracking nearly impossible. Too much snow—2 feet or more—leads to an energy-zapping plod and indiscernible tracks. Crusty snow is too noisy, resulting in spooked bucks and frustrated trackers, while dead-calm days and ultra-cold temperatures cause equally maddening outcomes. Conditions are everything, and they are almost never perfect. Tracking is a low-percentage strategy no matter how you look at it. But then there are days when everything comes together.

With a crusty snow in the southern Berkshires, Blood wanted to reroute to New York. But when he hit Exit 1 on the Massachusetts Turnpike, he started seeing fresh snow on tree limbs.

“I jumped out of the truck at a rest area and saw that there was nearly 4 inches of powder. I was thinking, This could work,” he says. “What I call a deer-killing day is when there’s fresh snow on the ground and a wind. It takes away a buck’s senses, and everything’s moving in the woods. That’s the high-percentage day we hope for. We wait all season for a chance to hunt that.”

When it comes to giant-whitetail potential, the Berkshires of western Massachusetts won’t ever be confused with Wisconsin, Iowa, or Kansas. Blood stepped into that buck-poor terrain for the first time, after the bow and general-firearms seasons ended. He had never been to Mount Greylock before, but he headed there anyway, got a motel room nearby, bought his license, and popped open his laptop to figure out a good way to go in the next morning. Using intel from the license agent at Dick’s and state maps on the internet, Blood’s hunt took shape. It started with his strategy for hunting any new ground: striking out on foot and making a 1- or 2-mile arc in an attempt to find a good track. A track qualifies if it’s big, ideally a splayed and rounded print left by a 7- or 8-year-old buck. They’re usually 8 or 12 inches apart, side to side. Big bucks will drag their feet, even in light snow, so he looks for that too.

“If I can’t find an old toe-dragger track, though, I might follow a smaller one in the hope that it’ll take me to a bigger one,” Blood says. “Bucks will often cross paths. Any time you follow a buck track, it’ll take you to more deer.”

When he walked into the woods the next day, Blood struck tracks. He moved at a regular walking pace, trying to cover as much ground as possible without missing any clues. There was no dawdling. He might follow a stream, or he might run a ridge, but he’s always moving. In addition to tracks, though, he ran into other hunters, stretches of private land he couldn’t access, and heavy snow higher up the mountain that obliterated the fresh sign of the good buck he had been trailing. The buck was doing what many mature bucks do—following a doe track to see if she was still in estrus. With 8 inches of snow on the ground and more coming, however, the tracks were filling in quickly. It was time to call it a day.

Classic Clues

The next morning, Blood searched for more access points. There was some activity at the gate where he parked, and human tracks heading up the trail. So he decided to just go through the woods and not follow any trails. He found nothing promising at first, but after crossing a stream, he cut some sign—and the track of a really nice buck.

Mature whitetails that live in large tracts of roadless terrain can be enigmatic, even to the hunters who chase them. And this particular buck was no different. He was a roamer, which was just what Blood had been looking for.

“I’ve let a lot of bucks go either because it was too early in the season or I didn’t think they would weigh over 200 pounds dressed,” Blood says. “Also, I don’t want to shoot bucks anymore unless I’m tracking them. I like the challenge.”

Read Next: Snow Tracking Tips: How to Age a Set of Tracks

The buck’s winding trail was straightening out now, and Blood followed quickly to close the distance, hiking across a ravine and over a ridge. When bucks get ready to lie down, they’ll nip at browse and feed a bit, then often will climb to the top of a ridge where they can bed down and watch their backtrail—which is exactly what this buck did.

“I was easing along, trying to watch the cover carefully,” he says. “I was expecting that when he headed high, he was looking to bed. Then, just like that, I spotted the buck lying there in the snow. I don’t think that he ever knew I was there.”

Blood took the heavy-bodied 5-pointer with his front stuffer, a 5.5-pound Woodman Arms muzzleloader that he prefers for its ease of handling. It was his first Massachusetts whitetail, and he killed it just like he has many of his bucks: late in the season, after months of hunting pressure, in the heart of a vast woods.

“But it’s not about the kill—that’s just the end result,” Blood says. “These days, I don’t shoot bucks unless there’s a story or experience to go along with it. I guess it’s just the satisfaction of a good hunt.”