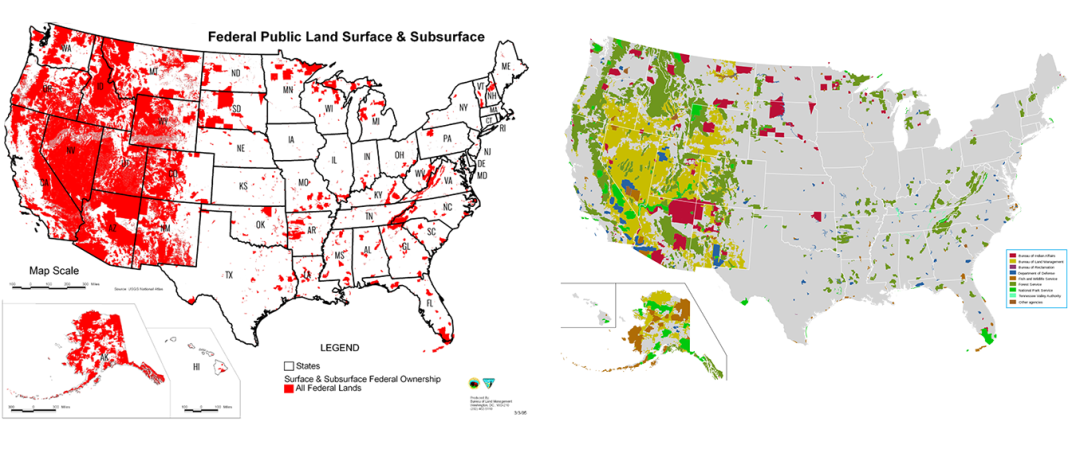

America’s federal government manages more than 640 million acres in the United States, about a quarter of the nation’s land. But an influential group of anti-federalists argues that that’s too much to be effectively managed, and its members are pushing legislation that would give or sell federal land to state and local governments, or even sell it to private entities in order to pay down the national debt.

Opponents of this federal-land divestiture movement say that states are ill-equipped to manage large blocks of public land because of the costs associated with fighting forest fires and maintaining roads, fences, and other infrastructure. Besides, selling the public estate, they say, is fundamentally anti-democratic. What’s really at stake here? Responsible use of public funds, for sure, but also hunting and fishing access, and a tradition of multiple use—logging, camping, cattle grazing, and mountain biking. Because of the ramifications to recreationists, we wanted to take a deeper look at some of these public-land issues and opportunities.

On Oregon’s rural coast, the proposed sale of a state forest provides a lens into the policy choices that define ownership of our public land in America and the challenges of keeping it public.

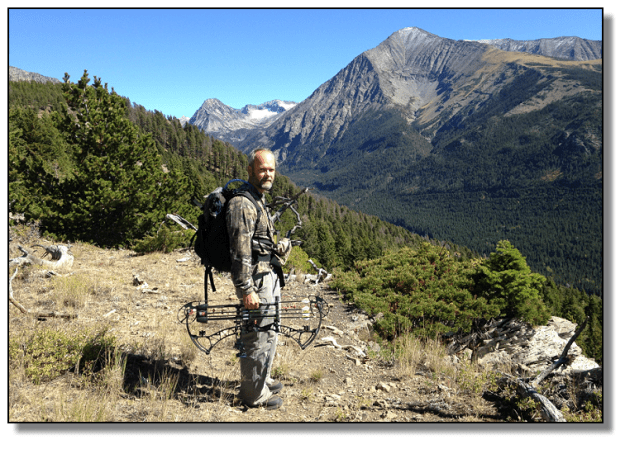

But not all state land is endangered. In Montana, hunters pay a pittance—as little as $8 annually—to roam millions of acres of accessible state land. That small investment ensures hunters have a voice in access and land-management decisions.

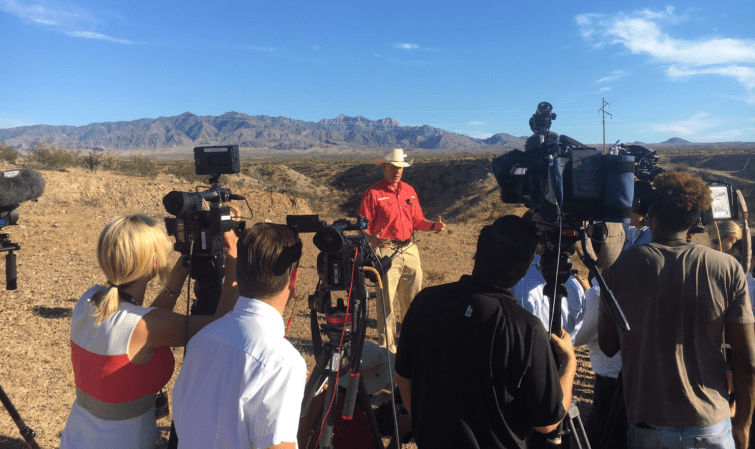

One of the perspectives that has been missing in the national discussion about federal-land management is that of the land managers themselves. So we asked one—a retired Forest Service district ranger—about what it’s like to spend taxpayers’ money on the ground and manage land for multiple uses. And we highlight specific parcels of federal land that are in trouble across the nation, and detail the threats that could jeopardize recreational access.

Paradise Lost

On Oregon’s southwest coast, a cherished public forest was almost sold to a private buyer, raising questions about the viability of states as landlords.

The story of Oregon’s Elliott State Forest begins and ends with the trees. This 82,000-acre expanse of fragrant red cedar, mist-dripping hemlock, and towering Douglas fir was designated in 1930 and named for Oregon’s first state forester. The land, consolidated from various federally owned parcels and logged-out private sections, was intended to be a state-owned timber factory, a place where trees could be grown, then cut when they matured, and the lumber from them would be sold to build houses and swing sets. A state law requires revenue from timber sales on state forests be used to fund Oregon’s schools.

For 60 years, the trees kept growing and the loggers kept cutting and selling them, the proceeds building schools from Pendleton to Portland. Hunters discovered that the steep canyons and ferny glens of the Elliott hid shade-loving blacktail deer and gnarly-antlered Roosevelt elk. The streams of the forest offered good fishing for coho and chinook salmon. Families from nearby Coos Bay and Reedsport camped on the Elliott over long holiday weekends. The oldest state forest in Oregon was public, open to anyone. The sound of the place was the two-stroke whine of a working chainsaw.

I lived in a cabin on the edge of the Elliott for the summer of 1985. I caught my first sea-run salmon there, and I saw my first Cascades elk in an alder fen up Wilkins Creek. For me, a Missouri farm kid exploring what seemed like endless public land with a fly rod and a backpack, the Elliott represented paradise.

For the state, it also represented profit. A half century of timber sales from the Elliott generated about $12 million annually.

But in 1990, the northern spotted owl was listed as a federally endangered species. The Elliott Forest’s extensive old-growth timber was a stronghold of the cat-sized owl, and under conditions imposed by federal regulators, the amount of timber cut on the Elliott and neighboring public and private forests was restricted in order to preserve owl habitat. You can date the new story of the Elliott Forest’s trees to about that time.

Additional restrictions on logging that followed—designed to protect habitat for marbled murrelet, Pacific lamprey, and coastal salmon—meant fewer trees were cut and less money flowed to Oregon’s schools. Since 2013, the Elliott has actually lost several million dollars annually.

Environmental regulations have slowed timber harvest on neighboring federal and private land, but because the Elliott’s charter depends on generating money for Oregon’s schools, the state earlier this year reached a decision that’s been a couple of decades in the making: The Elliott State Forest would better serve school budgets by being sold, with proceeds from the auction going into an interest-bearing escrow account.

No Easy Answers

Oregonians have been polarized by the choices framed by the proposed sale of the Elliott, which would likely mean closing most of the forest to the public. Sportsmen and -women from around the nation are paying attention to the fate of the forest because it represents more than the loss to the public of a single property. The Elliott could be the future of public-land ownership in the West.

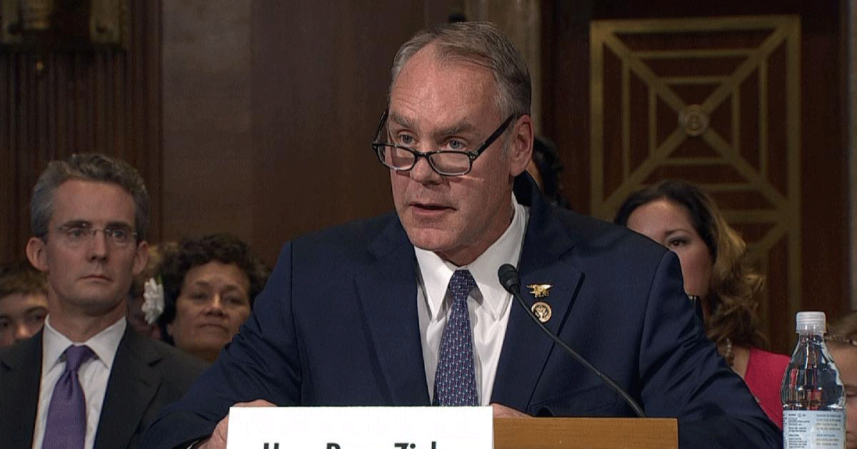

At the same time the Elliott Forest’s fate is being decided, Congress and state legislatures are weighing the question of whether the feds manage too much land in America. Critics claim that federal acreage would be better managed by state and local governments, which are more responsive to local constituents. They have worked with state legislators to develop a list of federal properties that could be “disposed” to local governments or private entities.

“Distant, unaccountable federal bureaucracy is blocking public access, increasing wildfires, destroying our environment, and decimating communities,” says the pro-divestiture American Lands Council on the homepage of its website. “It’s time to restore balance so willing states can tend our unique public lands with local care.” The potential sale of the Elliott excites divestiture advocates as a small step toward right-sizing what they think is a bloated and out-of-touch federal government.

Divestiture opponents point to the Elliott as evidence that if federal parcels transferred to states don’t make money—through resource extraction—then cash-strapped states will be pressured to sell them.

“The Elliott serves as a shocking reminder of how susceptible state lands are to fiduciary and political pressures,” says Jesse Salsberry, an Oregonian who is fighting the sale. And it “shows how quickly we can lose our traditional public access when states are faced with such pressure.”

But for now, it seems the Elliott will remain open to the public. In May, Oregon’s Land Board—the trustees of the state’s school-fund account—reversed its initial decision and opted to not sell the state forest to a private timber company. The forest’s future is still uncertain. The board is now considering selling it to Oregon State University, trading it for federal land, or lifting the restrictions that require the land to make money for the school funds. By removing the legal requirement that it make money from timber sales, maybe the Elliott could remain a productive piece of Oregon’s public-land estate. In other words, maybe the forest has a value other than the commercial value of its trees.

User fees—for campers, hikers, hunters, and anglers—are on the table. If stakeholders in the Elliott Forest sale can agree, then one of the best hunting and fishing grounds in the state can remain fully open to public use. If they cannot, then it’s likely to be locked up like so much private land elsewhere in the West.

Working Landscapes

In Montana, a hunting license includes state-land access.

Some states are capable public-land managers. In Montana, which has more than 5.5 million acres of state-owned land, public access and multiple use are high priorities, even though the state has the same school-funding requirement that dictates Oregon’s state-land management.

Sale of state land in Montana is a nonissue largely because funding is shared by all users, including hunters and anglers. Every Montana Conservation License—the prerequisite to hunt everything from upland birds to bighorn sheep—includes a state-land access license. Residents pay $8 and nonresidents pay $10 for the Conservation License; $2 from each license goes to the Trust Lands Management Division administered by the state’s Department of Natural Resources. In 2016, $990,000 in Conservation License fees went to the state’s school-fund trust account to compensate for recreational use of state lands.

In short, a basic hunting license provides access to some of the best wildlife habitat in Montana. When the federal government granted Montana statehood in 1889, it ceded two 640-acre sections in each township to the state, in order that revenues from them could fund the state’s school system. After more than a century of land swaps and consolidations, distribution of state lands has changed, but state sections—denoted in blue on most maps—are scattered across Montana. And as long as they are legally accessible by public roadway, accessible waterway, or through adjacent public land managed by other agencies, hunters and anglers can explore them.