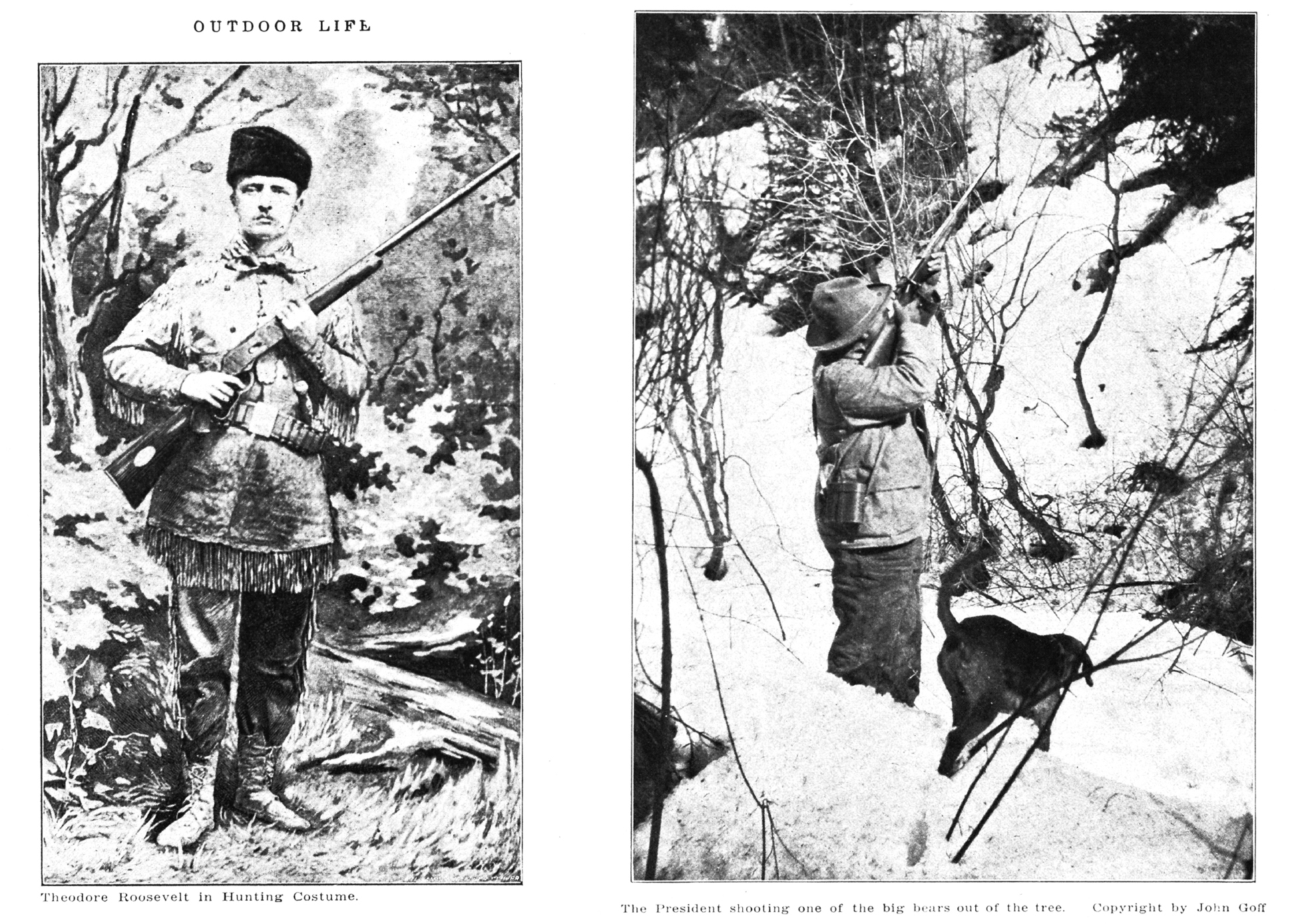

Editor’s Note: In the spring of 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt traveled by train to hunt bears and big cats in Colorado. The account of his hunt was published in the July, August, and September 1905 issues of Outdoor Life. The original story, simply titled “The President’s Bear Hunt,” began with an introduction by J.A. McGuire, the Colorado-based founder and editor-in-chief of Outdoor Life, who spoke at length with Roosevelt when he hunted Colorado as vice president and again on this trip. The story itself was written by one of TR’s guides, John Goff, who kept a diary during their weeks in camp. “[This] story is the only official account of the hunt furnished in any sportsman’s publication,” wrote McGuire. “Mr. Goff carried his own camera, from which several of the photographs here published were reproduced.” Goff’s original account spans dozens of pages and three issues; we have excerpted most of it below. This hunt occurred while unregulated predator hunting was taking place in much of the American West; for a history of how the president’s trophy hunts like this one turned into the hunting and conservation legacy he’s known for today, read about it here.

“The President’s Bear Hunt,” by John Goff

From the July 1905 Issue of Outdoor Life

Before attempting to describe President Roosevelt’s bear hunt in Colorado, I will first ask the readers of Outdoor Life to look for no prize essay or any pyrotechnic display of language. I am first, last and always a guide, and boast of no such splendid education as that with which most of the readers of Outdoor Life are gifted; but I do know a lion or bear track when I see it, and can generally follow the dogs on any kind of a chase, provided they keep their senses and do. not run me up too slippery a tree or over precipices that have a tendency to drop straight down.

After my ten or more years of continuous guiding in Colorado, one would think it might become tiresome, and that it would often seem very much like work to me. WeII, that is true, even, of the effects upon all hunters who seek big game. Some days they imagine they put in the worst hours of their lives (and probably do) but the next day their efforts may be crowned with such success that their troubles of the preceding day are forgotten and they think only of the exultation in seeing that huge hulk of destructive animal flesh drop from the tree at the crack of their gun, or that bear that has fought off the dogs for a half hour, heave over and roll down the hill as their bullet penetrates a vital point.

Those bright, happy moments are not soon forgotten, but are carried in the memory’s looking glass for a long time. It is the recurrent thought of them that makes us long to again hit the trail and listen to the music of the dogs.

And so it is with me. After each hunt I breathe a sigh of relief-in a certain sense—but when the next trip is on I feel as much enthused as I was on the last one.

About April 7th [1904] saw me a pretty busy man, for that was the day on which I left Meeker, Colorado, with my sixteen dogs and twenty horses, to join my guiding companion, Jake Borah, at New Castle. For some time we had been “graining” the horses and keeping the dogs in shape, until, when I left Meeker on that date, I believe I had as perfect an outfit of dogs and horses as was ever gotten together in one bunch in the West.

Three riding horses were supplied each member of our party—the President, Dr. Lambert and Mr. Stewart. The President wore a canvas suit most of the time, with medium length ordinary hunting boots, a soft, light colored felt hat, and usually a handkerchief thrown loosely around bis neck. He used a .30-40-220 new army Springfield rifle that was especially made for him. (On his first trip in Colorado he used a .30-30 Winchester).

On the evening of the 11th (four days before the expected arrival of the President) we had a light fall of snow which continued for the next two or three days. All this time Borah and I were out with the dogs, riding the hills, looking for bear sign, in which search we were unsuccessful. … On the 14th, Borah, Wells and I went down to New Castle to meet the President and his party. They arrived the morning of the 15th at 8 o’clock, in their private car. The President was eating breakfast when the train pulled in. He immediately quit the table and went to the rear of his car, from which he made a short speech to the 1,500 people who had congregated to see him. He afterwards went back and finished his breakfast.

The President’s first mount was “Old Fred,” an Oregon horse which I secured for him-a splendid roadster but nothing extra in the bills. His other two mounts were “Martinus” and “Jumbo,” horses with records for good work on bard climbing trips.

At 11:15 on the morning of the 15th we started on the eighteen-mile ride to camp the President and B. P. Wells (one of our best guides) in the lead, Mr. Stewart and Dr. Lambert next, and Borah and I taking up the rear with the remainder of the packs and the dogs. A chorus of shouts arose from the crowd as the President was bidden god-speed on his trip. Within a half mile of the depot we were lost to view in the foliage and draws of the hills.

We reached camp at 4:30 p.m., where Jack Fry had dinner ready. The party sat down to a bill of fare of chicken pot pie, stewed tomatoes, mashed potatoes, hot biscuits, corn cooked in cream, canned peaches, pumpkin pie and sauces. The President ate heartily, remarking as be finished: “This is better than we have at the White House; I feel that I ought not eat any more, but Doctor, please pass me another biscuit.”

On the 16th (Sunday) the President consented to accompany Dr. Lambert and Mr. Stewart on a reconnoitering trip, looking for sign and to get used to the saddle. Borah, Welss and I went out with them, taking along the dogs, and starting at 8 a.m. We started for the Pinon Ridges, north of camp, which was in lower country, expecting we might at least run onto a bob-cat track.

The scouts, who had been over this country before, had not seen any favorable bear sign, so we only took along a few of the dogs. Going down the creek a mile or so we soon began to ascend a steep divide, finally reaching the summit, from which we were afforded a commanding view of the country to the north-even across the Grand river and clear into Rio Blanco county. We followed along a ridge for some distance, Borah and I finally landing out on the sharp point of this ridge, where a couple of days before we had seen quite a little cat sign. About five miles from camp we made a circle, turning backward toward camp. We struck here a fresh cat track, which the dogs ran and then lost. We all hurried to the point of a cliff, from which we could watch the interesting work of the dogs working out the track on another ridge. After they had worked over into the second gulch my dogs, ‘Gene and Badge, suddenly quit the cat track and ran onto a bear track. Hearing the dogs tonguing on the bear track, we all looked carefully, when Mr. Stewart exclaimed “Bear!” and pointed to a brown bear coming down the opposite side of the cañon [sic] with Gene and Badge after him.

Borah and I started down the cañon at a good gait and succeeded in turning the bear, which went back into the same locality from which he had just come. After sizing up the situation and realizing the lateness of the hour-besides not having as many dogs as we needed-we decided to pull off the dogs and return to camp, preferring to again continue the chase in the morning. After being called off the bear track Badge and Gene came back and joined the other dogs in the bob-cat chase. After the space of a half-hour or so we heard the dogs barking “treed!” and we all hurried to the spot to find that a lively-looking cat had forsaken Mother Earth for a more secure, though less comfortable perch in the branches of a cedar. Before any photos could be made of his catship, Shorty, my bull-terrier, climbed the tree, and at the distance of thirty feet from the ground, jumped for the cat, causing both to fall from the tree. Badge, another dog, caught the cat on the fly as she fell, and the next instant all the dogs were on the little yellow animal, making short work of her. We then went to camp and resolved to make an early start the next day.

On the second day of the hunt (or the third from New Castle) we went back with the full pack to the head of the gulch where the day previous we had seen the bear. When we got to within thirty yards of the track by which the bear had crossed over the ridge, the dogs “winded” the track and became very unruly. Old Jim got especially so and broke away from me. A minute later we decided to turn them all loose. From that time on we had a warm chase, running the bear from 11 a. m. to 12:45. We were favored by being on the opposite side of the ridge from the dogs, and could see them all the time.

Soon we brought him to bay on a big rock, where he stood defiantly fighting of the dogs. Borah said to Anderson, one of the guides: “Go up above and ‘shoo’ him down by throwing rocks at him.” The idea was to get him down so as to save the President climbing the steep and rocky hill, which was too precipitous to take a horse up. After Anderson had climbed the hill and as he approached the bear he bolted and ran around Anderson to a little pocket in the gulch. Then the balance of the party, Borah and I in the lead, decided to ride up a little ridge and get onto the bear from another quarter, as it was evident he wouldn’t tree. By the time we reached our desired goal Anderson had gotten around him. He threw rocks at him and encouraged the dogs to such an extent that he found it was advisable to desist, as he feared the dogs would rush in and get killed. So he stood and watched him until the party got up.

When we got to within 100 yards the bear started around quartering from us, going onto the opposite hillside. Wells was in charge of the President’s gun and he handed it to him, as there was a chance for quick action. It was a chance shot (there being but a space about a foot across that was not occupied by dog flesh) but the President took it, and hit the bear in the thigh, which caused him to roll down the hill turning somersaults and biting dogs as he went. The dogs and bear rolled down together, the dogs piling up on the animal on a ledge on the side of the gulch.

While he was yet rolling I grabbed the President’s gun and said “Follow me!” We worked our way down onto a ledge directly above the one on which the bear was located. When we reached the ledge we found we were about sixty feet above our game and in a position from which a fair shot could be had. It was lucky we got on this ledge, for, judging by the way that bear was making mince-meat of dogs, it would only be a question of time until he would kill off half of them. The President took careful aim and shot the bear in the upper part of the neck, which caused him to settle down for his last sleep. That was where the crippled dogs began to show up. Old Spot (one of Borah’s fox-terriers) was found holding tightly onto the bear with his back broken, but game to the last. The bear had bitten the little fighter through the back and he suffered so that Borah ordered him taken away and shot to end his misery, as it was impossible for him to recover. Shorty, my bull-terrier, was also badly crippled, and I carried him to water, where I left him temporarily, as there was no way of carrying him. The next day Wells went out after him, finding him huddled up on the hillside too stiff and sore to walk home but too nervy to die. After some coaxing he was induced to walk a little at a time, and after he got limbered up he hobbled along fairly well.

He walked all the way to camp (as it would have distressed him more to be carried) and came in with a grin, although he had been bitten through the front shoulder and the thigh. Dr. Lambert then and there christened him the “toad-faced dog.” After examining the hide of the bear we found its upper lip all cut up where “Shorty” had locked teeth with it. The bear weighed 350 pounds before being dressed.

From the August 1905 Issue of Outdoor Life

This naturally put new life and ginger into the members of the party, as well as the guides and everybody having anything to do with the hunt. And further encouragement was instilled owing to the fact that the bear was of no mean proportions. The skin after being taken off measured seven feet six inches from nose to tip of tail and six feet six inches spread of forepaws. The President was in the best of spirits and now said that the hunt was a success, even if not another bear was bagged.

On the morning of the 18th, Courier Chapman made his first trip to Glenwood Springs with the mail, carrying also to the taxidermists the hide of the first bear killed. Borah and I went reconnoitering with the party, but on account of the hard work of the day previous we didn’t stay out long. The best we could find was an old bear track about a week or ten days old. On the 19th, Borah, Wells, Anderson and I went to Garfield Creek with the party—a long, hard ride of thirty miles for the day over rough and hilly country. It snowed nearly all day, and the travel was otherwise impeded by the necessity of going through much deep snow, in many cases the drifts being three to four feet deep. We returned to camp rather disconsolate, having seen no fresh bear tracks whatever.

That day Secretary Loeb came over to camp from Glenwood Springs with Courier Chapman, his first visit to the camp. On riding into camp that evening and finding the secretary there, the first thing the President asked for was news about the Russian-Japanese war. On the morning of the 20th the secretary went back to Glenwood Springs with Courier Chapman. It snowed all day and the party rested in camp, rather glad to have a little surcease from the saddle. The presidential party spent most of the time reading and playing whist. On the 21st Borah and I took the party out looking for cat sign. The other guides and helpers rounded up the pack horses and made the other necessary preparations to move camp to about ten miles west of the present camp, which move it was decided to make the next morning. As the country about the old camp had been pretty well hunted out, and as some favorable reports bad come in from the other section, we thought our luck would be better in the West Divide Creek country. We came back to camp that day without seeing any very encouraging signs of bear, and retired with hopes that our new camp would bear better fruit.

On the 22nd we moved camp. Borah and I with the party, hunting all the way over, the pack train tacking up the rear. We found nothing—not even a bear track. On the way over the President had a touch of the Cuban fever [a strain of malaria], the first of the trip, but which has often annoyed him since those memorable days spent by him in the late Spanish-American war. On this day a report came in from some ranchmen that they had two bears located, but when we reached camp we found they had killed them themselves.

On account of the unnecessary excitement which they caused us, we would have thanked them very kindly to have kept the news to themselves.

At this stage of the hunt we began to wonder and speculate on how many more bears we would be able to land for our distinguished guest. Borah and I often exchanged significant glances on this subject, and, while we didn’t say much, we thought awfully hard. We had now been out from New Castle just one week and had only bagged one bear, which we all considered hard luck. Yet the President was jolly and thought we were getting along swimmingly. It was certainly hard to put a damper on bis spirits, and I really believe that if we never got another but that one he would have gone back the happiest member of the party.

On Sunday, April 23rd, Borah and I went scouting west of camp and were rewarded by seeing the fresh track of an old bear and yearling on Alkali creek. On this day Wells and Anderson also went reconnoitering up West Divide creek and returned to camp with the information that they had seen the fresh track of a bear about two years old. A ranchman came into camp telling us that he saw a large, fresh bear track about three miles up the creek, on a tributary of West Divide creek.

This being Sunday, there were many visitors in camp to get a look at the President, and while he would have preferred to rest unmolested, it was hard for him to do anything else but receive them. Men came in singles, in pairs, with their boys, with their girls and with their wives. Whole families flocked in, their faces being a study of mingled curiosity and excitement. In every case the President was most courteous and obliging.

On the morning of Monday, the 24th, Borah, Chapman. Wells, Anderson and I went to Alkali creek with the President and his party, intending to follow up the tracks that Borah and I had seen the day before. When we reached the bear trail we turned the dogs loose, but they didn’t get to work right-seeming to be on the track of a bobcat or some animal smaller than a bear. The packs also gave trouble, causing much delay.

We rounded up the dogs again (the tracks being in dry ground and about three days old) and got them off in a bunch, tracking the bear right up to the edge of the snow. Where they entered the snow they were only about twelve hours old. We had held the dogs back for some time before reaching the snow, but now turned them loose again. They ran up into the tall spruce where the snow was four or five feet deep. We could plainly hear them tonguing, and occasionally got a glimpse of them when they ran out over a snowbank and no timber obscured the vision. Soon, however, their bell-like notes grew fainter and later could not be heard.

In this chase thus far we had trailed the bear about five miles. It was now about 2 p.m. when we tracked him to the edge of the snow. We cut across to a ridge, keeping lower down, where the snow was not so deep, as it was impossible to follow where the tracks led in the heavy snow. When we got over onto the next ridge we could hear the dogs baying, seemingly about a mile away, far into the snowdrifts. We had to go through snow three or four feet deep to get to the dogs (or to where they were when we beard them baying) but when we reached that spot we found they were about as far away as when we started. It was plain to be seen by the baying and by the disturbance of the snow along their trail, that the old bear was making stands at intervals and fighting off the dogs.

We found that in order to get over ground at all, we had to get out of the snow it being too deep to allow of any progress. So we gradually worked our way around to the south side of the hill, which was comparatively free from snow. When we reached this side of the mountain we could locate the clogs, which seemed to be barking “treed.” We started straight for them, but had to forsake our horses and walk, on account of the deep snow.

We reached the dogs and found a cub treed, which Dr. Lambert quickly dispatched. It seems the old bear had gone right on, leaving the cub treed. Soon we followed after the old one, whose trail led us out of the basin in which we were, over a steep and precipitous ridge. We had no easy time getting up there with our horses, as the side of the eminence was not only very steep, but slippery and brushy as well. When we reached the summit we overlooked a heavily-timbered spruce cañon [sic], and found that the old bear had preceded the clogs about three-quarters of an hour in passing over the top. We could hear the dogs barking in the cañon below us, evidently working down.

The snow was too deep to follow right down, so we followed along the ridge for about a mile. We stopped to listen and heard the dogs barking “bayed.” Then we lost no time in picking our way down through the thick quaking aspens. Down timber and snow, for about one and a half miles, breaking a trail single file for the horses. It was now 4 p. m., and they had been going since 7 o’clock that morning and were therefore tired. When we got down off the knoll we found the dogs were baying in a thick bunch of spruce. As we approached nearer we saw the old bear, treed in a big spruce, about thirty feet from the ground.

The President came up and, after careful aim, shot her in the neck, the bear crashing through the branches to the ground, as limp as a rag. This all happened after 4 o’clock in the afternoon and we were fifteen miles from camp. We therefore hurriedly dressed the animal and pulled for camp, which we reached at dark.

On the morning of the 25th, Mr. Stewart went home, planning, however, to return as soon as his business would warrant. On this day we went to Mam Creek (in the same locality as that in which the bear of the previous day had been killed) to take the track of some bears that a party had located for us. We reached Mam creek, fifteen miles, at 11 o’clock, and finding the tracks of an old bear and a couple of yearlings, we turned the old dogs loose first.

We were on a sharp ridge when the dogs were turned loose, the tracks leading up into the heavy spruce and snow. The party couldn’t follow us, though, so they went around for an easier trail. When they got near it was found that the dogs were working hard, the old bear and her two yearlings being seen running up through the spruce, the dogs close up. It was indeed a grand sight, and on0 which none who saw it will ever forget.

After we had stood and listened awhile we heard them bark “treed” up near the top of the ridge. When we reached them we had the enviable spectacle of two yearlings in one tree, perched about sixty feet up. After Dr. Lambert had killed the yearlings the party went up to the top of the ridge to meet Borah (who had not come down) while Anderson and I went around by a lower route with the dogs, starting them on the old bear’s track. We found she had evidently made a circle, going into the next cañon, and from the eminence on top of the ridge the party could see the race in all its vigor and excitement. Here the race was viewed, as it appeared, on the opposite side of the cañon. for fully two miles. I joined the party on top while they were watching the chase, and soon we heard the clogs barking “treed.”

We started up to where they were, but found we couldn’t go all the way with the horses, so tied them and tramped on top of the snow, which here was from three to four feet deep on the level. We soon reached the tree where the dogs were setting up a deafening noise, and found her bearship located on a spruce limb about thirty feet from terra firma. She eyed us with some misgivings when we had all congregated below her to get a peep at her shape, and cast anything but “goo-goo” eyes at the dogs as they frantically barked and jumped with glee.

When the President came up he gave her a dead shot in the region of the heart and she rolled out and down on the ground, where the dogs were on her in an instant, tugging and pulling at her inanimate carcass. After skinning her we rode to camp, twenty miles, where we found that Jack Fry had prepared his usually toothsome supper which this time consisted of chicken pot pie and all the et cetera that go with a really good camp meal. Thus ended the first ten days of hunting.

From the September 1905 Issue of Outdoor Life

These last days (with the exception of one—when Dr. Lambert was so fortunate as to bag four) were probably less exciting than the previous ones. One reason was the very disagreeable weather, which kept us in camp a great deal of the time; the other was probably the fact that only one of the ten days brought us any lucky in the bruin line.

Any man, however, who has hunted big game, realizes the fortunes attendant upon such hunting, and few of those who have successfully followed the hounds for cougar or bear expect so very much. They all know from hard-earned experience that bears and lions—and even the insignificant little bobcat—do not grow on every tree, and that sometimes weeks are spent in their pursuit before the luck is finally turned. I have hunted for bear—in particular on one occasion, when in company with the editor of this magazine—right close to them, for two solid weeks without a day of rest and without hanging a hide. Finally when we did strike bear they were quite plentiful.

The President, being a man who has hunted and killed bears before, knows this, and therefore had some idea of what to expect. I hope the readers will not misunderstand means making excuses for a poor trip. I am not attempting to do such a thing, for we had one of the most successful bear hunts—if not the most successful—ever pulled off in the United States. But I merely wish to mention some things to show that all the bears in one county of Colorado could not be rounded up on one short trip, and to also show that no one can tell what success may be had on a bear or lion hunt until the same is over and the hides are counted.

When this hunt was first planned, I was asked about the possibilities—that is, the number it was thought could be secured in the time which the President had at his command. This was to me a hard proposition, for while I knew about how many there were in a given space of country over in my section—north of Meeker between the Bear and the White rivers, close to where the President had hunted lions with me on his first trip—yet I disliked very much to commit myself as to how many we could promise him in that territory. Mr. Borah was then asked the same question, as to how many he thought his territory (south of the Grand river) would yield in case the hunt should be held there. Mr. Borah gave an estimate, which was satisfactory to the President and to Mr. Stewart, but even his seemingly conservative estimate was in excess of the number secured. It was not due, however, to any over-rating which Mr. Borah had placed on the outcome, but more particularly to the bad weather conditions prevailing during the trip. Mr. Borah’s territory was therefore chosen in preference to mine.

I am often asked “What kind of dogs are best adapted to bear and lion hunting?” My answer has been that common curs have done me more service than the finely-bred dogs of any breed. I have in my pack—and name them here in the order of their efficiency—foxhounds, bloodhounds, crossers between these two, bull-terriers, fox-terriers, fox-terrier crosses with other terriers, and canines that can only be called just “dog.”

While the greatest essential of a bear dog is the sense of scent, yet there are other qualifications that crowd this one awfully close, such, for instance, as that of worrying a bear and causing him to lose time by fighting off the dogs, which in grizzly hunting especially, is a valuable aid. Then the hunter can come up and get a shot; or if a black bear, this worrying process will soon cause him to tree, when of course the chase is ended.

With the fighting and worrying of the bear by the dogs is combined by the essential of being able to run in and nip and then get away before the powerful paw of the bear can land. This habit is only acquired by actual bear hunting, and is one of the dearest lessons the bear dog learns, for nearly all my dogs have at one time or another—in some cases many more times than one—received chastisement from bears which impresses vividly on their minds that they must hurry after biting the bear if they would continue to grace this terrestrial sphere with their presence.

A bulldog of a bull-terrier is one of the hardest dogs to teach this lesson of self-protection. Owing to their disposition it is hard for them to let go in time to save themselves, while they will rush in (at first) on a bear or lion, absolutely unmindful of the consequences.

The first lesson is invariably taught by the despised little porcupine, but even this does not remind them that they must be careful of bears. After one or two clouts from the big paws, however, they realize that care must be taken—that is, if they survive the blows.

On the 26th of April—which was the eleventh day of the hunt—we remained in camp and all rested up. It was a good thing for the dogs and horses , as they had been going pretty hard and pretty regularly since the hunt began. About noon of that day the President had a touch of fever, but remained up and chatted with the members of the party as if nothing was the matter. It rained that evening, but it threw no damper on the ardor of the party nor stilled the flow of anecdotes, stories and reminiscent talk that came from the distinguished gathering.

On the 27th the fever which the President noticed the preceding day had not abated, so he remained in camp all day. Borah, Fry and I, in company with Dr. Lambert and Mr. Stewart, went up Divide creek for a short distance, soon branching off on a fork of this stream, called the Muddy. Up this we traveled for a couple of miles, and soon took up the cold trail of four bears, which a Mr. Johnson had located a few days before. The tracks appeared to be about four days old. Borah and I put the cold trailers on the tracks, holding in the young dogs. We cold-trailed them for eight or ten miles, consuming about three or four hours’ work, following them over creeks and up and down the gulches. Finally we sighted the four bears, which had been lying in a gulch a half mile ahead of the dogs, and who on hearing the dogs had jumped.

Up to this time the dogs had been cold-trailing—not as yet having come up to where the tracks were fresh. After seeing the bears we examined the lay of the country very carefully and decided to go down a ridge, around the point of which it was apparent the bears would go, intending to turn th young dogs on the trail as the old dogs came by us.

It was some twenty minutes or more before the dogs showed up. Then we turned all of them loose that we had with us, but they got a little confused, about one-half of them taking the back trail. After running for over a half mile they saw their mistake and finally came back and followed it right. They ran for about a half hour, after which while rounding a little ridge, we heard them barking “treed.”

We hurriedly went up and found one of the yearlings in a tree (Jack Fry had along his bull-terrier, which, after seeing this bear treed, followed the other bear tracks and wasn’t seen for three days). Dr. Lambert wasn’t long in shooting young Bruin out of the tree, for we were all anxious to follow the trail of the other three as quickly as possible.

Some ranchmen were with us that day, and when the cub was killed they asked if they could not have the meat in return for their trouble of skinning it and carrying the hide to camp. Of course we readily acquiesced, as it assisted greatly in getting started on the trail of the others. These ranchmen seemed to bob up at the most opportune times, and if it were necessary to carry anything to camp or do us a favor, it seemed there was always a ranchman, or a ranchman’s son, who seemed ever and over-willing to do our bidding. The same condition prevailed around camp. There was always someone nosing around who would grasp at the opportunity of doing something for us, in the hope that he might get a look at the President or receive a word of greeting from him.

After disposing of the yearling and giving the ranchmen instructions, etc., we were on the trail of the others. The dogs made a run of about three miles, when they again barked “treed.” We reached the tree , and to our delight found it contained another yearling. The doctor shot it, and we lost no time in getting the dogs off on the trail of the remaining two. When this one was killed by Dr. Lambert we found there was another obliging ranchman on hand who was willing to accept the bear meat in exchange for the trouble of skinning and carrying the hide to camp. (While Mr. Stewart followed us each day yet he never carried a gun—preferring to allow the courtesy of killing the game to the President and Dr. Lambert.)

The dogs only ran about a half mile when the yearling branched off form the trail of the mother. Drum—one of my dogs—followed it, the young bear circling round almost to where we were, where it treed. The rest of us followed the dogs after the mother. It seems that the old bear had circled more in their direction and away from us, and had treed very close to them. After the doctor had killed it they fired a signal and we came up, finding when we arrived that the bear had been skinned out. We started for camp about dark, tired but very jubilant over our success. This completed what I believe was the hardest day’s work of the entire trip, and one which also bore the greatest fruit. It was a hard jog for the horses back to camp, as they were already pretty tired, but such must be expected in bear hunting.

While we were talking of the merits of bear dogs at camp that evening one of the ranchmen asked why Shorty—my bull-terrier—wasn’t able to cold-trail with the rest of the dogs. I replied that his ears were too short to smell a track. This seemed to please the President immensely.

On the 28th the President felt much better, but we decided, nevertheless, to rest up after the hard work of the previous day, as the dogs and horses needed it badly. We therefore loafed around camp and while the President and his party engaged in congenial conversation we busied ourselves in looking after the outfit. Of course we were besieged with visitors, all anxious to see the President, many of whom were favored not only with a look at him, but by cheerful remarks on the success of the hunt.

The President decided it would be best to move to our old camp on East Divide creek, as he preferred to finish the hunt there, planning to hunt on Garfield creek and over the mountains to Glenwood Springs as a wind-up of the trip. But each day afterward stormed and kept us in camp, with the exception of a couple of days when we started out but were driven in by the storm. On one of these occasions—May 5th—we killed a bobcat.

On May 6th we pulled camp and started for Glenwood Springs—the President, Mr. Stewart and Dr. Lambert going first by horseback and arriving in Glenwood Springs at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. We followed with the packs and dogs and got there about 3:30, where we found a royal reception awaiting the President and party.

Before concluding my account of probably the greatest and most important bear hunt ever taken anywhere, I want to mention the banquet which the President gave at the Hotel Colorado, Glenwood Springs, just before his departure for the East. The guests of honor at this spread were all the guides and assistants who did the work for the party while out, including, of course, Mr. Borah, the cook and myself. None of us will ever forget that spread. I can yet see the look of joy and satisfaction which mantled the good-natured face of our President when he sat down at the table and beheld seated about him the weather-tanned and mountain clad men who were his sole companions for three weeks in the hills.

Why, dear reader, it was worth a fortune to look at the President on that occasion! His good-natured, health-glowing face—fresh from the air and sunshine that gives life, blood and energy to all beings who seek it—fairly beamed as he looked from one to the other of us about that festal board and recalled the incidents of the trip just ended.

None of us had on boiled shirts or white collars, swallow-tailed coats or low-cut bosoms. We came as he requested us to—in our mountain clothing—the very togs in which we were dressed while hunting bears with him on Garfield and Divide creeks. It was as he wished, and besides, it was very convenient to us all, as most of us wore the only clothes belong to us between Glenwood Springs and our home.

The President made a short talk, but it was not of the conventional order. It was full fo feeling and referred to many of the thrilling incidents of our hunt. It was expressive of the utmost satisfaction over the results—and of course such remarks (and he often made similar ones) always made the guides feel good.

There is just one more thing which I am going to say before closing this story, and which I hope will not be objected to by the President: He showed his lover for our American boys by making a present of $50 to each of Mr. Borah’s two young sons; and the same amount to each of my three. It is needless to say that this money will ever be needless to say that this money will ever be prized by these boys and their parents—not particularly for its intrinsic value, but from the fact that the greatest President the United States has ever known was thoughtful enough and kind enough to remember them in so liberal a manner.

Read more OL+ stories.