We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

FOR A WEEK we had been hunting chukars above the Snake River in eastern Washington, my son Chris and I, laboring along those god-awful lava slopes each day and getting back to camp late, bone-tired and rock-sore. We were set up just across the river from Lewiston, Idaho, where Jack O’Connor lived. I’d meant to call him and let him know we were around. But as the week wore on and we wore with it, getting raunchier by the day, we didn’t figure the O’Connor hearth would be much enhanced by our presence.

I should have known better. The next time we stopped at Paul Nolte’s Lolo Gun Shop in Lewiston there was a message waiting: “Dammit, call me. O’Connor.”

By phone, Jack told me he didn’t give a hoot how we looked. He’d seen dirty Levis before. “When you get in from hunting today, come on up to the house,” he barked. “We’ll have a libation and look at some stuffed animals. Then we’ll eat beefsteaks someplace. Adios.” Click.

The libations were waiting when we got there, and the stuffed-animal tour got under way. It was something, it really was, although I can’t recall many details. Hides, horns and tusks, cases of superb custom rifles and shotguns that dreams are made of. Shelves of classic books bound in buckram and leather. And in the high-ceilinged trophy room, the big heads the grand slam of sheep, the stately racks of elk, caribou, moose, mule deer, kudu, and orderly benches with reloading presses, and racks of dies and components. Then back by a slightly different route, past more hides and oiled walnut and blued steel.

If I was dazed by all this, 19-year-old Chris was stunned. He hadn’t said a word. When we got back to the living room, Jack asked:

“Tell me, Chris, have you ever seen anything like that before?”

“No, sir. I sure haven’t.”

“What do you think of it?”

“Well, sir,” said Chris thoughtfully, “you don’t fish much, do you?”

In the 20 years I knew Jack O’Connor, it was the only time I ever saw him at a loss for words.

As a matter of fact, Jack hated fishing. And for a gun editor, surprisingly, he wasn’t exactly breathless about handguns, either. But when it came to the long guns, and applying rifle and shotgun to the taking of game, he was deeply experienced and expressed that experience in some of the best writing that’s been done on the subject.

Jack was one of my guiding lights in the late 1930s, when I was beginning to shoot and hunt. He was one of a special band of dream-spinners called gun writers—men like Bob Nichols, Col. Townsend Whelan, Maurice Decker, Ned Crossman, Phil Sharpe and Elmer Keith. I savored their exploits on the target range and in the field, coveted with wonderful guns they pictured and praised, and tried my best to apply what they taught me to my old low-wall .22 and the local farm thickets.

I don’t know how many of those old-time gun writers and editors really hunted. Some of them, like some of today’s shooting writers and editors, probably hunted little or never. But there’s no denying O’Connor’s credentials in that department. His hunting skill went beyond basic shooting ability and coolness in the presence of game, although he had developed great measures of each. Jack also knew the game he hunted. He knew what it took to hunt and kill that game decently, and even more important, he knew what the game needed from the land if it was to withstand hunting pressure. He wasn’t just a sometime shooter who could turn a clever phrase. He was a hunter who’d been there and done it, and it showed. It always shows.

Jack relied heavily on personal experience, but he was enough of a technician to distrust isolated examples and fluke occurrences. He preferred to test a bullet, cartridge or rifle in many ways before drawing a conclusion. I don’t think he ever felt really familiar with a particular cartridge until he had hunted with it. Sure, he reported on new loads and rifles tested only on the bench, but his gilt-edge endorsement was generally reserved for guns and ammo proved under rigorous field conditions.

To the shooting public, Jack O’Connor’s middle name was “.270 Win.” He was the cartridge’s official press agent—so outspoken in its praises that he had a sort of spiritual copyright on it. The .270 may have been Winchester’s baby, but Jack was its adopted daddy. This got a bit wearisome in his later years. He was sometimes a little touchy about his public identification with the .270, but he brought it on himself with glowing anecdotes like this one from his story “Up to Our Necks in Deer”:

“Whoopee!” said Zefarino. “That’s the kind of rifle I like, one that has power. One shot and the buck doesn’t move. How do you call it?”

“The .270,” I said.

“The same you shot the ram with, no?”

“The same.

“With the .30 you shot a buck and it ran. Then the smaller boy shot a buck with the .25 and it ran. Now the large boy shoots a buck with this rifle and it is dead in its tracks. How good a rifle, this .270!”

“It shoots a good ball,” I said. “A very fast ball.”

So spoke O’Connor, and the .270 flourished apace. And characteristically, Jack knew whereof he spoke. He’d wrung out the .270 on three continents. He shot at least 36 species of big game with this cartridge. These included more than 30 rams (four grand slams of American mountain sheep and four Old World species), an even dozen moose, more than a dozen black bears, two grizzlies, at least 18 elk, 17 caribou and several species of deer. How many deer? I doubt if even Jack knew. He also used the .270 in Africa on such tough game as oryx and zebra, as well as ibex, gazelle and antelope in Iran and India.

In many ways, Jack was in the catbird seat as a gun writer. He developed during the 1920s and 1930s when great advances were being made in really modern rifles, sights and cartridges. It was a time when the bolt-action sporting rifle and its high-intensity cartridges began to really come into their own. New powders and primers and revolutionary bullet designs were appearing, telescopic sights and mounts were evolving rapidly, giant strides were being taken in fitting rifle actions and barrels into one-piece stocks, and men were revising what they’d known about accuracy. Jack O’Connor knew many rifles and shotguns, but he’ll always be most closely identified with the superbly accurate, strongly breeched, bolt-action rifle with ’scope sight and fast, jacketed bullet. After all, he was mainly a man of open country, of mountains and plains and deserts, and this showed in his interests and preferences.

As a gun writer who depended heavily on hunting mileage, he had plenty of grist for his mill. Born in Arizona Territory in 1902, he grew up in a hunter’s paradise that still had overtones of the Old West, next door to the game-rich desert wilderness of Mexican Sonora. He’d begun writing during a period when new road systems and air travel were opening up many remote hunting ranges in the West, British Columbia, the Yukon and Alaska. He had served his apprenticeship at the close of one era and the beginning of another.

I first met him in the fall of 1958, at the first Winchester Gun Writers’ Seminar, at Nilo Farms in southwestern Illinois. Those were some fandangos, those early seminars, including such scribes as Warren Page, Pete Kuhloff, Larry Koller, John Amber, Pete Brown, Dave Wolfe, Elmer Keith, Les Bowman, Col. Charley Askins, Bill Edwards, Tom Siatos and such notable drop-ins as Col. Townsend Whelan, Nash Buckingham and Andy Devine.

I’ve never laughed harder, learned more, or had days and nights pass any faster than at those early Winchester seminars. Rich talk and wild tales, all leavened with deep experience and salty humor. How I wish we’d taped some of those sessions in the old Stratford Hotel! About half the guys were more or less deaf, of course. A conversation between Jack O’Connor, Lee Bowman, John Amber and Elmer Keith could be heard through most of the hotel. A stranger might get the idea they were violent antagonists yelling at each other. Not so. They were good friends just trying to hear each other after too many years of unshielded muzzle blasts. And later on, after dinner, we’d all convene for the main bullshoot with half of us sitting on the floor while actor Frank Ferguson, Pete Kuhloff, Andy Devine and other masters vied in round-robin story contests that would send us to bed at 3 a.m., completely laughed out.

Yet, I don’t think I ever heard Jack O’Connor tell a joke at one of those shindigs. He just wasn’t a joke-teller. His style of humor was anecdotal. You never belly-laughed at an O’Connor story; it was wry, dry and low key. His humor lay in the sardonic twist of real experience, and he often used it to make a point. For instance, this comment on rifle stock design:

“Sometimes very slight changes in curves and angles make the difference between a beautiful and graceful stock and a homely and ordinary one. I am thinking of two sisters I once knew. Both were blond, witty and charming. But one (though she was a fine cook and had a heart of gold) was a rather ordinary-looking lass who got by on her good disposition and winning ways. The other was a tearing beauty, a creature so lovely that one look at her sent young men’s blood pressure skyward and set them to uttering wild, hoarse cries and tearing telephone directories apart with the bare hands. Yet actually those two girls looked much alike. It was easy to see they were sisters. What made the difference was an angle here, a line there, small dimensional differences in eyes, noses, mouths. And so it is with stocks.”

Jack was a great admirer of the late H. L. Mencken and shared many of that great man’s views on the sad state of the English language and the world in general. Like Mencken’s, even Jack’s compliments could have a wire edge. I once spoke at a dinner meeting that Jack attended. I can’t remember the subject now, but Jack came up afterward and said: “Well, that wasn’t quite as bad as I thought it would be. It was fairly tolerable—although as a rule I hate afterdinner speakers like God hates St. Louis!”’

He spoke with authority, for his wife, Eleanor, was a St. Louis girl. Jack met her at the University of Missouri. Still, I couldn’t let that slight to one of my favorite cities go unanswered. I loved to needle Jack.

Jack was a durable man and well designed for his calling, seemingly made of slabs, laths, bits of wire and scraps of leather.

A couple of years later, coming into Lewiston from Missoula, I passed a pulp mill whose sulphite stink tainted the air for 10 miles up the Clearwater. When I saw Jack, I gave it to him: “O’Connor, don’t you ever badmouth St. Louis again! Why, I can’t wait to get back to the Mississippi and away from this west Idaho stench! Come home with me, Jack, and breathe some good air for a change!”

He gave me a long, level look through those wire-rimmed glasses of his. You could almost hear the gears meshing. He asked: “Madson, tell me something. How much does Remington pay you to work for Winchester?”

“Not enough!” I said without thinking.

“AGREED!” Jack yelled triumphantly. It made his whole day.

We had some good yarning sessions on guns and hunting, although near the end of his life it seemed that Jack was less disposed to talk about guns than other subjects. And a thing he never tired of discussing was writing.

Jack was a trained journalist with years of teaching at Arizona universities. All that showed, too. His work was disciplined, carefully controlled and structured. It wears well. Jack never used a heavy word when a light one would do, and he seldom used any word carelessly. He was a relentless self-editor who knew that simplicity and directness are the essences of good communication. His sentences were short, crisp and to the point. No, come to think of it, they weren’t always short. As a fine double-gun seems lighter because it is well-designed and balanced, so Jack’s longer sentences usually seem shorter than they really are.

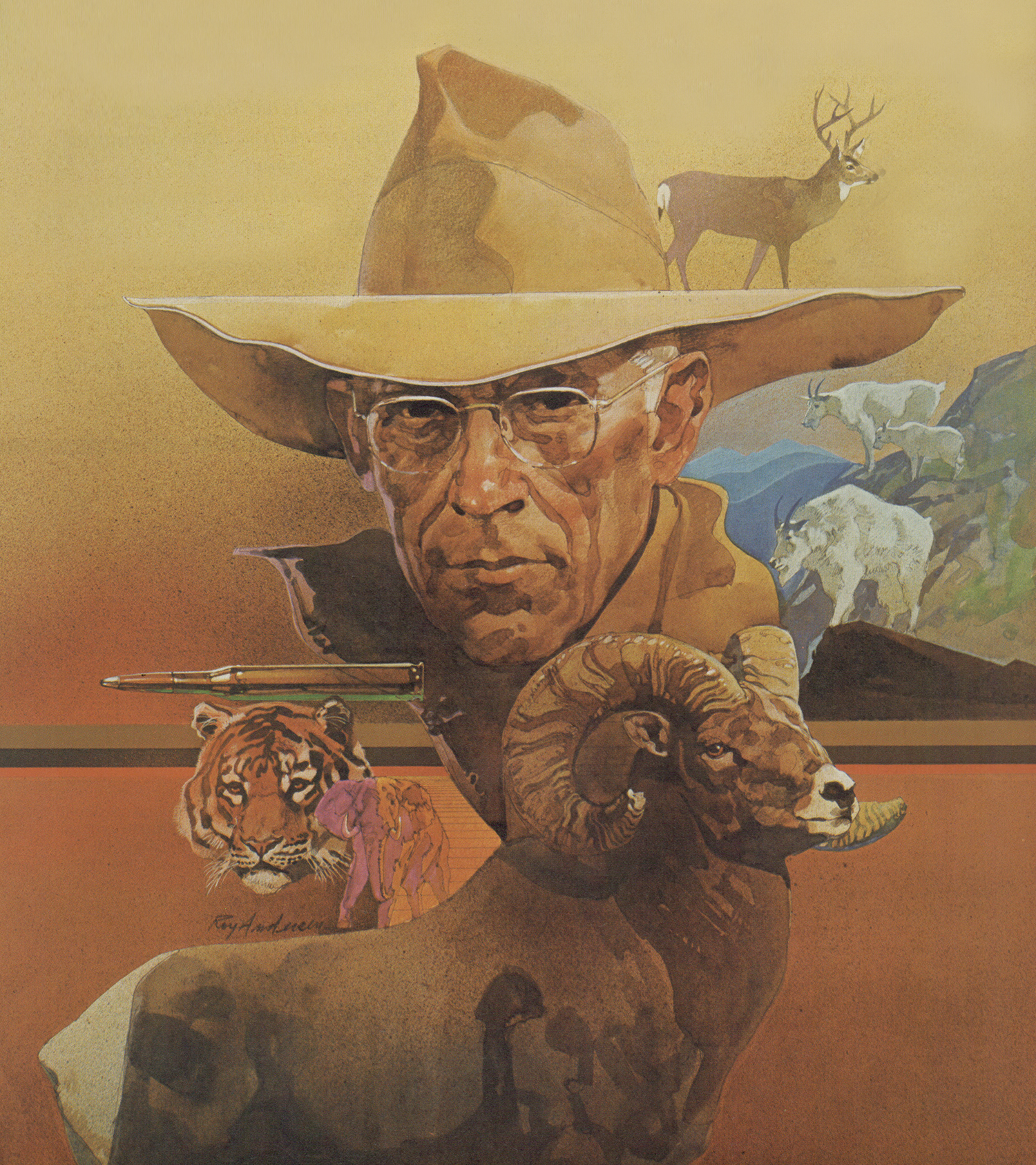

Jack was a durable man and well designed for his calling, seemingly made of slabs, laths, bits of wire and scraps of leather. He had to be named O’something. With that long upper lip and wire-framed specs, he was Paddy to the life—and the older he got the more Irish he looked. Now and then he’d wear a shapeless tweed hat that someone had given him; all he needed then was a blackthorn stick to be the image of a reformed Donegal poacher.

He was also inclined to be a dour man. He was outspoken and intolerant of those he considered fools, phonies or bores, and some of his bitterest opinions were reserved for writers who produced what he called “the vast amount of vague, windy, sloppy and sometimes dishonest writing that is put out about rifle accuracy.”

Most of Jack’s career was linked with Outdoor Life. He wrote his first piece for OL in 1934—a conservation story titled “Arizona’s Antelope Problem.” He did several more stories for the magazine during the mid-1930s, and late in 1936 editor Ray Brown asked him to write exclusively for OL. Jack accepted, and took a year’s leave of absence from teaching journalism at the University of Arizona to write magazine stories and work on a book. Thus he entered the rarefied world of freelance writing.

He was back at the university full-time, and still doing articles for Outdoor Life, when shooting editor Ned Crossman committed suicide in 1939. Jack was asked to replace him, and began doing a regular department called “Getting the Range.” In the June 1941 issue Jack was named arms and ammunition editor and continued in that job until 1972. During his years with Outdoor Life he wrote more than 200 articles for the front of the book, in addition to shooting columns that appeared almost monthly for about 43 years. No other gun writer has racked up that much mileage with one magazine.

Jack retired officially from Outdoor Life in 1972 although he served as shooting editor for another year after that. During those last years I hunted upland birds in level fields with him. He got along fine, but his mountain days were about over. He’d been in a bad car wreck in 1957.

Jack died on Jan. 20, 1978, aboard a cruise ship returning from Hawaii, just two days before his 76th birthday. His wonderful wife and favorite hunting companion, Eleanor, was with him at the end—and followed him within the year.

A few years before Jack left Outdoor Life we were yarning away an autumn evening in Lewiston, talking about hunting in general and gun writing in particular. Jack had been reflecting on the old-timers—Whelan, Sharpe, Nichols, Crossman and the rest-when he suddenly turned to me and said: “John, how in hell can they ever replace me? Who can they find who’s seen what I’ve seen, and can write about it?’’

My first impulse was to land on him for such a typical O’Connor remark, but after a moment’s reflection I understood. No one could really replace him. He was the product of a special time, and we’ll not see his like again, for the country and experience that shaped Jack will never exist again. He couldn’t be replaced; he could only be succeeded and by a younger man who’d write for today’s shooters, sharing their problems and hopes and not letting the rich memories of vanished places and long-ago hunts sour today’s adventures. A successor like Jim Carmichel, who Jack approved as “a good writer and a very knowledgeable young man.” Coming from O’Connor, that was about as good as anyone will get.

The epitaph of Western artist Frederic Remington is simply: “He knew the horse.” If two generations of shooters and hunters were to rephrase that, Jack’s stone would say: “He knew the rifle and loved the game.”

Good hunting, old friend. See you in camp at sundown.

This story, “Remembering Cactus Jack,” originally appeared in the July 1980 issue. Read more OL+ stories.