Bundy Trial Simmers in Nevada

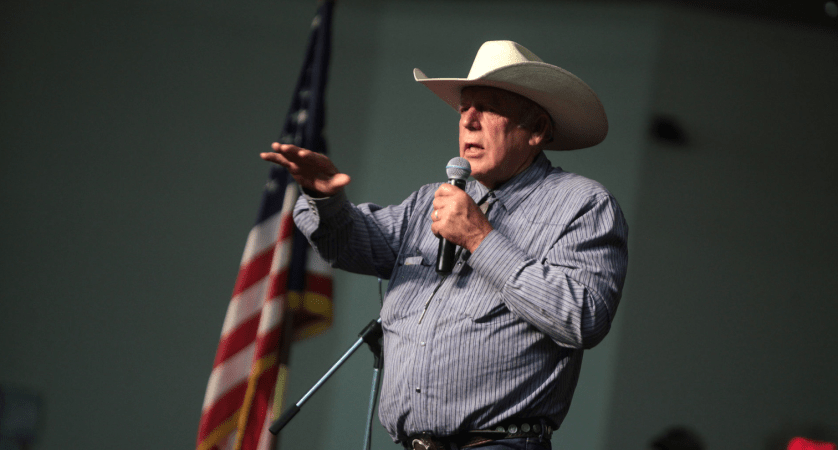

The Nevada family that has spearheaded anti-federal lands protests in the West will soon see trial in the Silver State, as proceedings begin to decide the fate of Cliven Bundy, his sons, and their followers.

They are awaiting trial on charges they lead an armed clash with Bureau of Land Management officers in 2014. The first three of 17 folks charged in that standoff are presently undergoing trial in the federal courthouse in Las Vegas, beginning with jury selection. Each faces 15 charges, including threats and assault on federal officers. According to High Country News, lower-level defendants will be tried first, followed by alleged ringleaders, Cliven, and sons Ammon and Ryan Bundy.

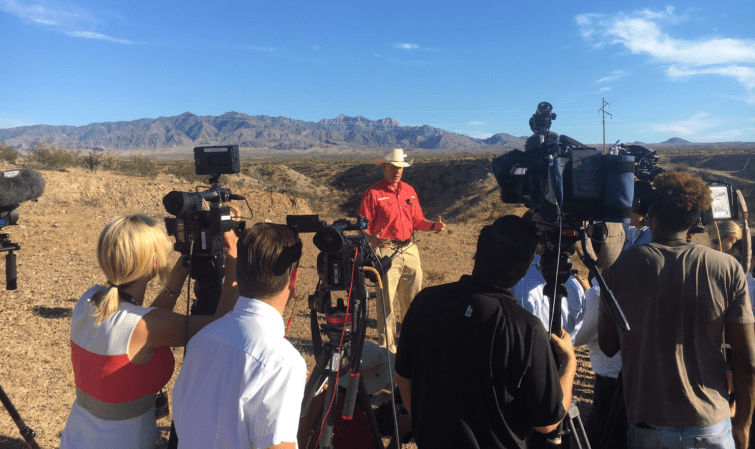

Cliven Bundy owns a ranch near Bunkerville, Nev., and grazes his cattle on surrounding public land. The BLM says Bundy has refused to pay more than $1 million in grazing fees over decades. After a protracted legal process, the BLM moved to remove the cattle from the public range in 2014. Rangers were met with Bundy and his armed supporters. Rather than risk bloodshed, authorities backed off, but pursued federal charges against Bundy.

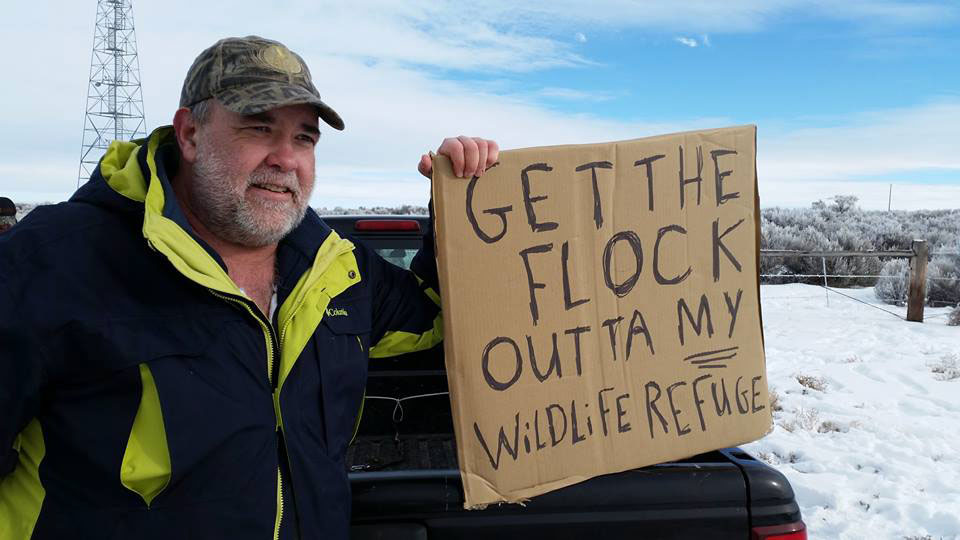

The elder Bundy avoided arrest for more than a year. He eventually was arrested in Oregon, where he traveled to visit his sons, Ryan and Ammon. Those two were arrested in early 2016 after they led a month-long occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. An Oregon jury acquitted the younger Bundys on conspiracy charges over the Malheur standoff. However, they remain in custody over the Nevada charges.

Even though the Oregon case is entirely separate from the Nevada proceedings, the Malheur acquittals hang over the Nevada trial. Prosecutors will be under a spotlight, while the defendants can’t help but feel a bit more optimistic after their surprise success in the Northwest.

On the topic of federal law enforcement…

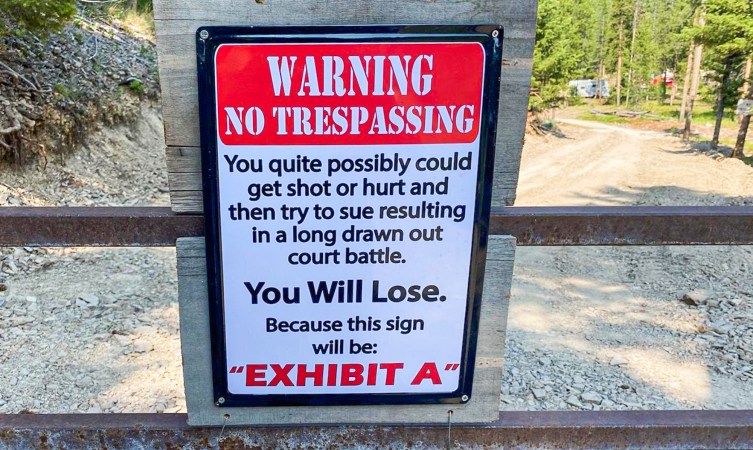

The Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association sent a testy letter to Rep. Jason Chaffetz, R-Utah, blasting his bill that would eliminate law enforcement on lands managed by the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management.

Chaffetz is an established critic of public lands. Earlier this year, he introduced two controversial bills. One of those, HR 621, would have sold off 3.3 million acres of public land. HR 622 would eliminate the BLM rangers and Forest Service law enforcement officers, replacing them with block grants to local counties. Chaffetz [hastily withdrew HR 621] after sportsmen’s protested; however, he has remained supportive of the companion bill.

The association of federal law enforcement said the bill will eliminate about 1,000 rangers, investigators, and law enforcement personnel who patrol America’s backcountry alongside local sheriff’s deputies and state game wardens.

“With escalating violent crimes, threats from drug cartels and remoteness of certain regions, Congress should be looking at prioritizing its resources toward strengthening the law enforcement functions of these agencies, rather than dismantling them,” wrote Nathan Catura, president of FLEOA.

Sheriff’s deputies do important work, Catura said, but they are no substitute for the passion and specialized knowledge about backcountry crime that goes along with natural resource law enforcement.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch…

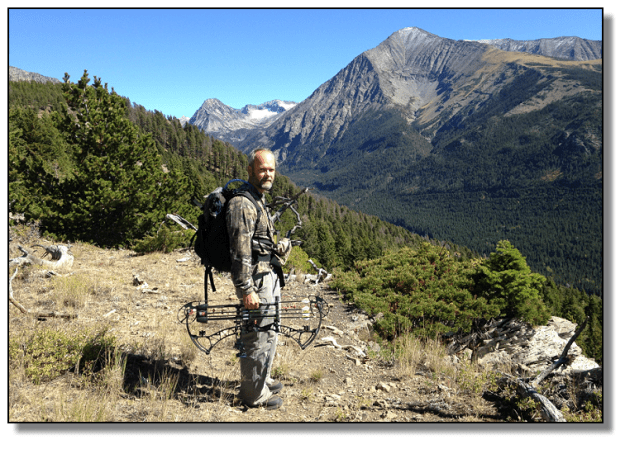

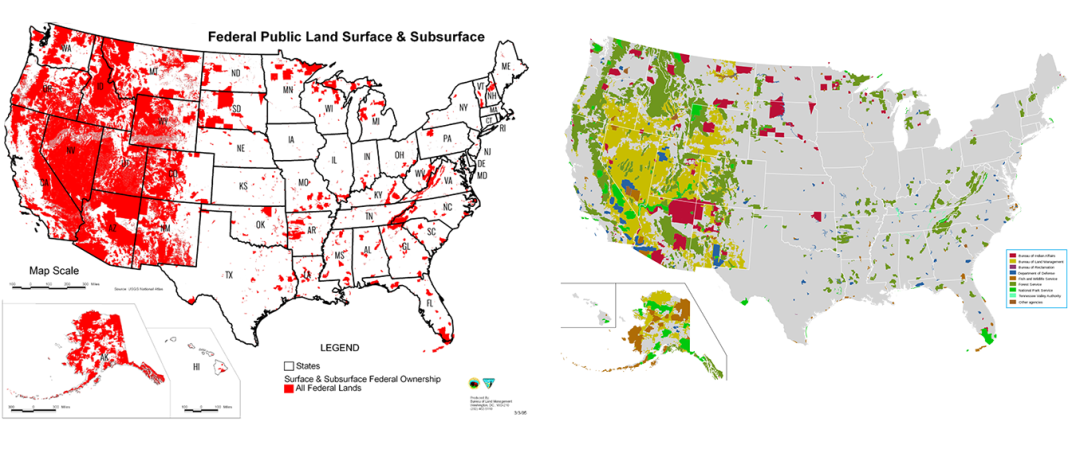

The BLM manages about 245 million acres in the American West, much of the basin-and-range sagebrush country so important for elk, pronghorn, mule deer, and sage grouse. It’s also important for oil and gas development and livestock grazing.

The agency has its hands full striking a balance for those often-competing multiple uses. Over several years, BLM has overhauled its rules for public planning. That is, the rules for how it will make tough management decisions involving wildlife habitat, and how it will gather input from recreation groups, industry, local governments, and other segments of the public.

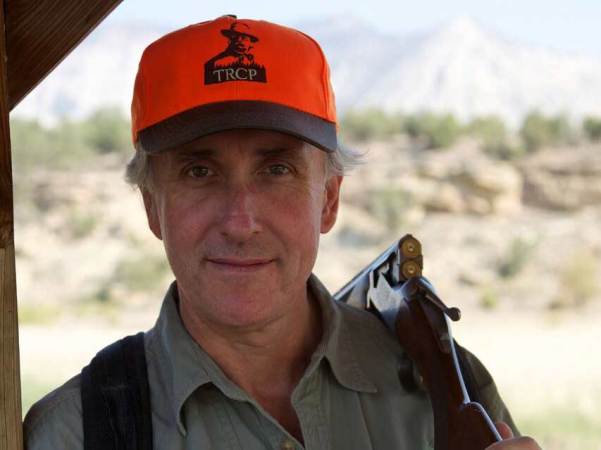

All was going pretty well until it got political. BLM came up with its basic land-management strategy, or “planning 2.0.” Sportsmen’s groups like the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership applauded the rules as providing for broad and meaningful public input, keeping the agency in line with the wishes of the public, which after all owns the land the BLM manages.

Yet some powerful special interests and their allies in Congress objected to the change. Earlier in February, the House voted to overturn the revised BLM rules. If the Senate agrees, all the work will be for naught and the agency will be stuck with obsolete planning rules dating back to the 1980s.

Now, sportsmen are gearing up to fight in the Senate to keep Beltway politicians from overriding the work of the professional resource managers in the field. The Senate could vote in a matter of weeks.

“This really should not be politicized,” said Joel Webster, director of TRCP’s Center for Western Lands. “If Congress rolls back this rule, sportsmen will find themselves silenced when it comes to the future of these important lands.” You can learn how to get involved at TRCP’s website here.