The amazingly symmetrical 10-pointer was a true tank, the likes of which I thought unimaginable in a country full of spikes and forkhorns. Had a trail camera picked him up in Illinois, Kansas, Iowa, or Wisconsin, he would have been designated a “target” buck. But this was New England, where target bucks don’t much exist. Low-170 bucks are outliers in a land of meat hunters. Yet there he was on the trail camera virtually every night for weeks in a row. Although mostly nocturnal, he spent considerable time munching on the clover, beets, radishes, and brassicas in my little food plot. I was stunned by his existence. I should not have been. I had been told that this exact thing would happen more than 20 years ago.

“These little seeds can help every hunter in every state grow bigger bucks.”

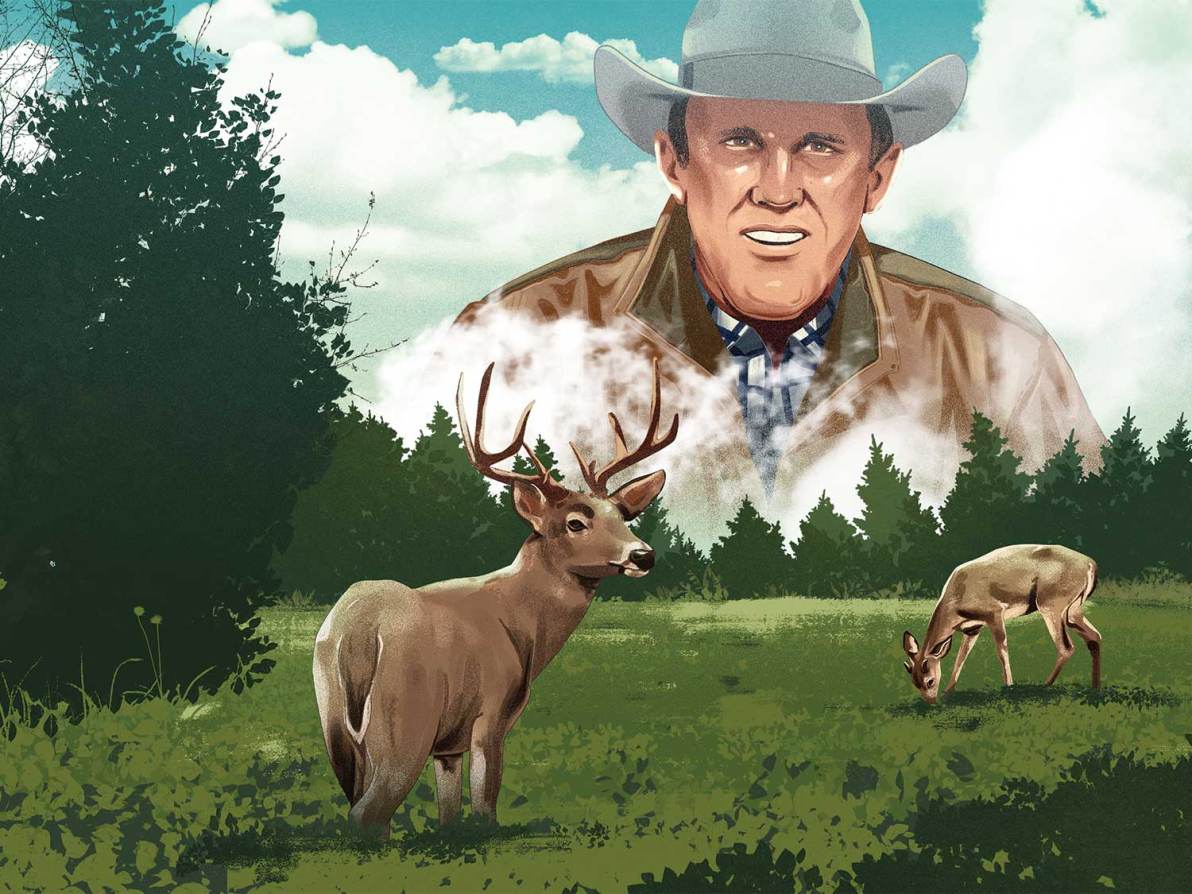

When you’re a 20-something associate editor at Outdoor Life magazine and the bombastic Ray Scott, founder of Bassmaster, is talking, you listen. In his hand was a small pile of tiny blue pellets, and he was talking about something called “food plots.” In the late 1980s, the term was wholly unfamiliar.

“Clover,” said Scott. “Whitetail deer love clover. Plow, lime, and fertilize a piece of ground. Plant these seeds and you will grow bigger bucks.” I scoffed inwardly.

But Scott and editor-in-chief Clare Conley hatched a grandiose plan right there in New York City—many miles away from any sort of tillable ground—that would forever change the path of whitetail deer hunting. Readers would be offered the chance to get a sample packet of clover seed in an upcoming issue by calling a toll-free phone number. Food plotting was born.

“Oh, I remember it,” says Whitetail Institute senior advisor Steve Scott, Ray’s son. “When the story hit offering some free seed, Ray was on the farm. The phone lines blew up and he started pulling people off of tractors and out of the fields to work the lines. That, essentially, was the beginning of serious food plotting. In many respects, it changed the course of everything.”

Read Next: A Deer for My Dad

It certainly did for me. As skeptical as I was of Scott’s boasts, I knew that it was time to make a serious change in my deer hunting strategy. I hunted tirelessly in a region where getting your buck was what it was all about. Venison trumped antler points. I had no problem with that at all (still don’t), but I also wanted more. With Scott’s ”enchanted beans” in mind, my first stop was Sears. The rototiller cost right around $500, and I wore it out. Tilling 2 acres of formerly unworked land with a walk-behind tiller was wearying, but the promise of giant bucks with big racks made the task less daunting. That doesn’t mean that I was hugely successful. Scattering $100 worth of clover seed felt satisfying as hell—and it came up well. But so did every other weed the good Lord ever created. Whether the deer were unaccustomed to fine dining or they just didn’t care, I don’t know. But I was not being overrun with whitetail traffic. I quickly learned three simple rules for food plotting.

- Take a soil test: They are inexpensive and the results will tell you how much lime and fertilizer you need in order to make your food plot successful. Without a soil test, you will be flying blind and spending money needlessly.

- Kill it off: No one likes to use herbicides, but I won’t even contemplate planting a plot without first killing off that which is underneath. In my experience, it’s simply a waste of time and money otherwise. Wear the proper protective equipment and spray. It’s the best way to get rid of weed growth.

- Never overseed: If a little seed is good, a lot of seed is better, right? Well, that’s not the case when it comes to food plots. Throw too much seed and plants will come up too thick and choke each other out for water and nutrients. Plant precisely according to the instructions.

When that giant 10-point stepped into my food plot on the last day of the season, I pretty much fell apart. Although I’d spent many hours spying on the plot both day and night, I was not prepared for this scenario.

Shaking horribly, I snicked off the safety on my shotgun when he got to within 100 yards and then waited for him to present a shot. It seemed as if he knew that I was there. He never made a sound despite the crunchy snow. At 50 yards he stared me down for several minutes. At 30 yards he finally turned broadside. I shot and he ran, but never made it out of the food plot. Whether the clover helped him grow his massive rack, I’ll never know. What I know for sure, though, is that on an icy cold December day, he was on the move for food. And for 20 years, I’d been growing it for him.