A widely publicized study from Penn State University and the Iowa Department of Natural Resources released last week indicates that a surprising percentage of whitetails in Iowa are infected with the same SARS virus that causes COVID-19 in humans. The study, which has not yet been reviewed by the authors’ peers in wildlife-health or epidemiological communities, noted that the highly contagious virus was present in about a third—94 of the 283—wild and captive deer sampled between September 2020 and January of this year.

The findings caused widespread alarm that whitetails can not only contract the SARS virus, but that they may be capable of incubating more virulent novel strains that could be re-transmitted to humans, making an end-run around vaccines.

The study also raises questions about how deer contract the virus, since they live in the outdoors and presumably aren’t in close proximity to human hosts, and whether or not an infected deer could sicken hunters who come in contact with freshly killed carcasses.

While disease ecologists are still parsing many details from the study, here’s what you should know about SARS in whitetails, and how to handle potentially infected deer in the field.

Can deer die from COVID-19?

Probably not. The study found that a third of Iowa’s whitetails were infected with SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19 in humans—but did not seem to be symptomatic or sick with the disease. Researchers detected the SARS virus in the lymph nodes of dead captive and free-ranging (wild) deer. Those deer were outwardly healthy specimens.

Can the deer I just killed give me COVID-19?

Again, probably not. While the researchers didn’t investigate whether infected deer could transmit COVID to humans, the risk is probably low, say epidemiologists.

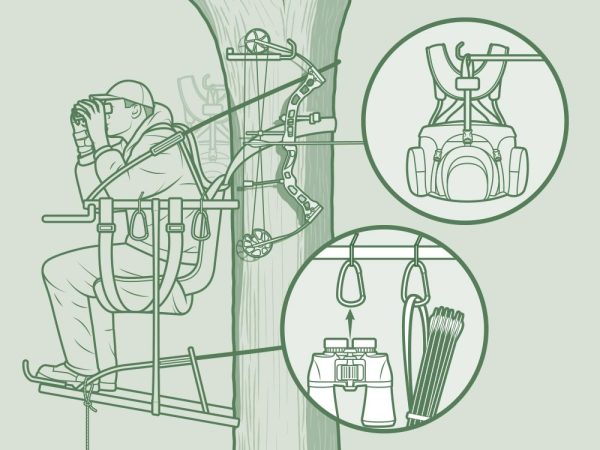

“The biggest risk for hunters is still probably their buddies in deer camp,” says Jason Sumners, Science Branch Chief for the Missouri Department of Conservation. “Transmission from a carcass back to a human would be extremely low.” However, he notes that guidelines from the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies stress that hunters follow standard precautions: wearing gloves when field dressing deer and washing hands after handling deer. Immunocompromised hunters might also consider wearing a mask.

Doug Schultz, spokesman for the Minnesota Department of Health, offered this:

“While the risk of acquiring COVID from wild deer is low, we would advise deer hunters to take precautions when dealing with white-tailed deer: wear rubber gloves and perhaps a mask when field dressing and processing; sanitize hands and instruments after dressing; and bag carcass remains before disposing in trash.” Hunters should dispose of processed deer carcasses in certified sanitary landfills, just as they have been advised by wildlife-health officials to contain the spread of chronic wasting disease.

Can I catch COVID from eating venison?

No. There is no evidence that humans can get COVID by preparing or eating venison from either wild or captive herds. Schultz says eating cooked venison carries little risk of transmitting any pathogen as long as it reaches an internal temperature of 165°F.

How did deer get infected with SARS?

This is one of the great unknowns from the research. Investigators have some ideas, but nothing confirms the path of infection. Rachel Ruden, Iowa’s state wildlife veterinarian and one of several authors of the study, told The New York Times that the virus might have entered the environment through sewage discharges or from deer coming into contact with human garbage or waste.

“Perhaps it doesn’t take much of a loading dose to get deer infected,” Ruden told reporters. “But either way, all of this is a striking example that we’re all in this pandemic together.”

Sumners says a good deal of effort is going to investigate this transmission link from humans to deer.

“It appears that the disease is transferred to deer pretty easily,” he says. “Simply too many cases being detected across the country for it not to be easy, what we don’t know is the source. I find it hard to believe deer are getting it from some random hiker/hunter/nature lover coughing in the woods. I could see that being the case for captive deer, like mink farms, household pets, and zoo animals. So how is it getting into the environment to infect deer? We know the virus can be detected in waste water, but what other potential sources of exposure exist? We just don’t know.”

Can humans get COVID from live infected deer?

This is another big unknown. One of the reasons the researchers released their preliminary findings was because they were “dumbfounded” by the SARS infection rates in Iowa’s deer herd. In fact, the research was prompted by a recent report that indicated 40 percent of free-ranging, wild whitetails in the U.S. have antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, suggesting they have had contact with the virus.

In Iowa, researchers found reservoirs of the virus in all corners of the state and in hunter-killed deer as well as those killed by vehicles. Equally surprising: the distinct strains of COVID carried by whitetails tracked very closely with the variants infecting the human communities in the same places at the same time, indicating a close transmission link between infected humans and deer. However, researchers have found no evidence—in Iowa or in many other places—that humans can catch COVID from deer.

In Maine, wildlife officials note that they have not yet tracked a case of a hunter contracting the disease from deer.

“This is just another wrinkle for us to keep in the back of our minds and keep track of as developments unfold,” says Nathan Bieber, deer biologist with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

Can humans contract COVID from other animals?

Given that the likely source of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was zoological—or originating in wild animals—epidemiologists have been on the lookout for other animal hosts. And they’ve found a disturbing example. According to a study published in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology, mink in a Danish fur farm became infected with SARS-CoV-2, which spread rapidly through the captive weasel population. The virus mutated as it passed among the mink, and a variant was then transmitted to humans. Virologists call this “spillback,” and it’s the real concern with virulent zoonotic diseases, says Missouri’s Sumners.

There is widespread evidence of spillover of COVID from humans to their domestic dogs and cats, and it has shown up in other non-human hosts, mainly zoo animals such as lions and tigers.

“So for deer, what do we know? Spillover from humans to deer, deer replicate it and spread it among themselves,” he notes. “We don’t yet have evidence that the virus has mutated in deer or that it has or will spill back into humans.”

Of course, the risks of deer-to-human transmission have grave health and medical implications. But demonstrated spillback could also fuel calls to eradicate America’s whitetail herd if there’s evidence that the species harbors COVID, allows it to mutate, and spills back to humans in an aggressively more virulent form. Imagine how a deer-removal campaign might be accomplished. And then consider how pushback to that deer removal campaign would make the resistance to wear masks in stores and schools look mild by comparison.

The authors of the Iowa study noted that: “In principle, SARS-CoV-2 infection of a non-human animal host might result in the establishment of a reservoir that can further drive the emergence of novel variants with potential for spillback to humans.” That sentence should concern any hunter with a pulse.

Are elk, mule deer, or even squirrels potential reservoirs for COVID?

That does not appear to be the case. In a landmark study that preceded the Penn State/Iowa DNR study, three species of deer were determined to be particularly susceptible to contracting COVID from humans. They are the Pere David’s deer, (also called the milu, native to China and is sometimes traded in the deer-farming industry), the various subspecies of reindeer (presumably including caribou), and the various races of North American whitetailed deer. While other species haven’t been as intensively studied, researchers with the American Society for Microbiology note that those three deer species have a particular predilection for binding the SARS-CoV-2 S protein from humans.

Are state game agencies looking at the prevalence of COVID in deer?

Yes. The Iowa study raised a lot of alarms in the game-management and disease ecology worlds. So much so that many agencies are looking at the viral loading of deer in their states. Missouri’s Department of Conservation is planning to test deer for COVID-19 this month, and according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, deer have been sampled in Illinois, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania. Samples indicate that at least seven percent of the whitetail population of the U.S. has antibodies for the virus. The highest viral load was in Michigan, where an alarming 67 percent of deer showed evidence of contact with COVID-19.

Captive deer were part of this Iowa study, and the spillover event reported in Denmark involved captive mink. Are captive populations of animals at a higher risk of both getting infected with COVID and potentially retransmitting variant strains of the virus to humans?

This is a fascinating part of the research. Missouri’s Sumners says that he will be interested in seeing how captive deer circulate COVID as compared to their wild, free-ranging counterparts. Of note is that the Iowa researchers tested lymph nodes in 132 captive deer and 151 free-ranging deer.

“How or will deer be able to infect humans with a mutated variant?” asks Sumners. “This is where captive deer would likely be the greatest risk, similar to the scenario that plays out on mink farms. It seems reasonable that the active infection in deer will/could give rise to new variants as it has done in the mink population. This is also part of the ‘why’ behind [disease ecologists’ interest in getting] better surveillance of disease distribution in deer. It’s also the only way we might detect any new variants that arise. Then what is the mechanism for transmission back to humans? Outside of a captive scenario, deer shouldn’t be in that close of contact with humans, but they shouldn’t have been that close to get it in the first place.”

The Iowa study’s authors actually provide a bit of insight in how likely and even where they think a spillback event might occur in free-ranging whitetails.

“Our findings raise the possibility of reverse zoonoses, especially in exurban areas with high deer density.”

In other words, those urban and suburban interfaces with both high human and deer populations could be the next incubator for a virulent strain of coronavirus. Whether that outcome becomes reality is like so many other questions in this chapter of the coronavirus infection: We simply don’t know.