If you’re a passionate waterfowl hunter, you might think you know how to cook duck. But do you really?

If your family hesitates to eat the duck dishes you prepare, or if you’re throwing away organs like the heart and liver, or you’re not making duck stock, then your knowledge of how to cook duck might not be complete, Jonathan Wilkins of Black Duck Revival tells OL. Wilkins is a hunting guide, wild game enthusiast, and writer. He’s passionate about getting new folks into hunting and teaching them about how to process and cook the birds they kill.

Wilkins shared some of his best tips and tricks for cooking duck so that you can spend less time researching recipes and techniques and more time on the water or in the kitchen.

How to Cook Duck: The Basics

Wild ducks are generally less fatty than domestic ducks you might find at the grocery store or butcher shop. (Don’t bother taking your wild ducks to a butcher. Instead, learn how to butcher a duck on your own.) While domestic ducks spend their days in a barnyard or a pen, wild ducks fly hundreds or thousands of miles twice a year, Wilkins points out. Because of this wild ducks carry less fat and their meat much darker and richer. That means they require a little extra care on the butchering table and in the kitchen. The number one rule—which is also the easiest to break—is to not overcook wild duck. This can be the difference between dry, tough, gamey meat and the best wild bird meat you’ve ever had.

Break Ducks Down

Like any other game animal, a wild duck’s body has a variety of different kinds of meat. First and foremost, Wilkins recommends breaking the duck down.

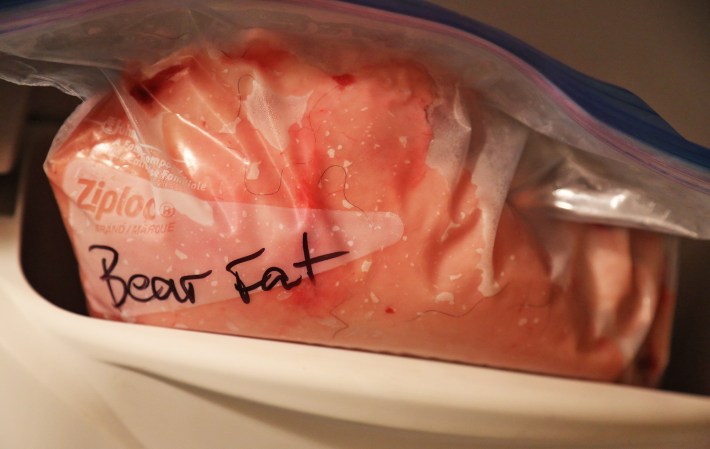

In general, puddle ducks should be plucked, leaving the skin on the meat. Divers and sea ducks should be skinned and their fat should be removed. Due to their diets, divers tend to harbor a fishier taste in the oils and fat beneath their skin. But that general rule doesn’t always apply. Canvasbacks are divers, but their favorite food is wild celery, which makes them one of the best ducks to roast with the skin on. Shovelers are puddle ducks, but you’ll want to skin those. Here’s a rough guide for which ducks to skin and which ducks to pluck.

Pluck and leave skin on

- Mallard

- Wood duck

- Gadwall

- Pintail

- Teal

- Canvasback

- Wigeon

- Bluebill

Skin and remove fat

- Bufflehead

- Scoter

- Shoveler

- Redhead

- Ringed-neck

- Long-tailed

- Goldeneye

Learn how to pluck a duck to get the most out of the best tasting species. But no matter what wild duck breed you’re working with, the breast meat is still the pièce de résistance of the bird and should be cooked like any tender muscle cut. The thighs and legs need the opposite treatment. These parts are full of cartilage, tendons, and other grisly bits, which lends well to long hours in a slow-cooker. The classic dish duck confit, or duck legs slow-cooked in their own fat and juices, are a standout example of how legs and thighs should be handled.

In order to get as much out of a single duck as possible, keep organs and carcasses, too. We’ll get to what to do with those in a minute.

Seared Duck Breasts

When you picture a classic seared duck breast plated with sides at a restaurant, you probably see fat that’s been cross-hatched with a knife and rendered down to a crisp. Wild duck breasts don’t require crosshatching, Wilkins says. Because there’s less fat overall, there’s no need to open it up. It will render on its own.

If you plucked your ducks and left the skin on, start the breast skin-down in the cold pan before it heats up to medium-high heat. This will help render the fat and crisp up the skin properly without overcooking the interior of the meat (pull when internal temp hits 130-degrees). If you skinned your duck, a hot-and-fast sear should get the meat to medium-rare. You can also roast duck breasts the same way—with the skin and fat face down in the pan. As far as seasonings go, salt and pepper is all you really need, or you can get creative with different spices. Wilkins points toward juniper and sage as a good flavor profile to try out.

“You’re trying to compliment and work with the natural flavor profile,” Wilkins says. “If you used really strong flavors on, say, turkey, it would overwhelm the flavor of the turkey. But if you’re doing it with a protein that has a deeper, more complex flavor, there’s room for the flavors to play together.”

Slow-Cooker Duck Thighs and Legs

Break out the crockpot, dutch oven, or sous vide for this part. Just like with any other tough cut of wild game, giving duck thighs and legs a full day on low heat will break down all the connective tissue, tendons, and even pull nutrients from the bones, while simultaneously rendering out fat and juices to make a satisfying, tender dish. Wilkins also recommends pairing duck legs with strong flavors, like those common for carnitas seasoning (cumin, coriander, garlic, oregano, plus salt and pepper).

Braised duck legs lend well to tacos, pasta, sandwiches, fried rice, and countless other meals. Or, keep it simple by slathering the meat in barbecue sauce and dumping it on a plate with some bread and sauteed greens, like Wilkins does in this barbecue snow goose confit sandwich recipe. For something a bit more advanced, slow-cooker duck also lends well to rillette, Wilkins says.

“Once you have those soft pieces, you blend up the meat with lots of fat and pack it into a jar. Then you can spread it on crackers with a charcuterie board,” he says. “But most of the time we’re just eating braised legs and thighs straight up, or doing a Cajun-style gravy over rice, or you can braise them, dredge them, and fry them up like wings.”

Frying and Smoking Duck

These are two more preparations that plenty of waterfowl hunters swear by. In both instances, Wilkins recommends breaking out the duck into various parts—breasts, thighs, and legs—before using either method. That will offer some freedom for how long you cook each piece to ensure each one gets exactly what it needs.

“Smoking a whole duck is a recipe for either overcooked breasts and tender legs and thighs or good, tasty, smoked breast and chewy, inedible legs and thighs,” Wilkins says. “You could part those out, smoke the breasts and do a quick sear on them. That would be delicious. Or you could take legs and thighs, brine them, smoke them, and that would be tasty. People want to smoke a whole duck and I just tell them it’s not the thing to do.”

If you’re determined to use your smoker, another option is to smoke duck sausage. Swap out your traditional venison or elk sausage recipe for duck leg and thigh meat and go crazy, Wilkins says.

As far as frying goes, brining, searing, or smoking the meat first before dredging and dropping it in bubbling oil will both help retain moisture and add extra flavor. The fryer is also a great way to cook offal—but it’s certainly not the only way.

Duck Heart, Liver, and Gizzards

If you’ve never experimented with wild game organs before, duck organs are the perfect introduction, Wilkins says. While other big game animals have more powerful, mineral-y flavors in their livers, or what Wilkins likens to “a soft bag of pennies,” duck liver is very pleasant. The heart and gizzards are other must-saves.

“With the hearts, I’d roast them over a fire, almost like yakitori-style. Grill them medium-rare, like little meat marshmallows,” Wilkins says. “If your ducks have particularly fat livers, you could do a pate. There’s also a great preparation I learned from Hank Shaw for gizzards. You do a quick corning brine on them then throw them in a crockpot and cook them in stock and you can just push them apart, they become so tender. You can serve those with braised greens, like corned beef and cabbage.

“But what I always teach in my classes is making dirty rice. Mince the heart, liver, and gizzards up, cook it with the trinity of celery, onion, and bell pepper, and it makes amazing Cajun fried rice.”

How to Brine Ducks

Wet brining a duck is the simple process of soaking the meat in water, salt, sugar, and spices to tenderize and moisturize it. This process is critical for cooking those fishier and tougher diver ducks, but it works nicely on all duck species. Ducks Unlimited has a tried-and-true recipe for a good salt brine:

- 1/2 gallon water

- 1/2 cup kosher or any coarse salt

- 1/2 cup brown sugar (optional)

- 1/2 cup pickling spices

Heat the water, add the sugar and spice until dissolved and then cool it fully in the refrigerator. Soak the meat in the mixture for 12 to 24 hours.

How to Make Duck Stock

Now that you have a carcass that’s been picked apart, grab some carrots, onions, and herbs, because it’s time to make stock.

Making duck stock is just like making any other wild game stock or bone broth. Chop up all your vegetables, bundle up your herbs, and throw everything—whole carcass included—into a giant pot. Simmer everything on the stove for at least 10 hours, giving all those bones, tendons, and bits of fat time to render down and release their nutrients. When you’re done, run the broth through a fine-mesh strainer and store it.

Wilkins uses one particularly genius storage strategy for his duck stock. Instead of storing it all in gallon freezer bags or quart containers, he pours some of it into silicone ice cube molds. When it comes time to saute some greens, deglaze a pan, flavor some rice, or do basically any other job that a bouillon cube would do, he drops in a wild duck stock icecube instead.

“Adding duck stock to a dish, it adds this burst of flavor that you’re not getting from other stuff.”

Read Next: Best Duck Hunting Shotguns

Some Duck Recipes to Consider

Here are a few standout wild duck recipes.

- Cured Wild Duck Breast

- Wild Duck Ramen

- Duck Apple Sausage

- Chinese Wild Duck Pie

- Wild Duck and Squash Curry

- Wild Duck Tacos

- Orange Glazed Duck and Wild Rice Stuffing

- Grilled Wild Duck with Sour Cherry Salsa

- Wild Duck Soup

- Wild Duck Cuban Sandwich

How to Cook Duck FAQs

The longer and slower you cook duck meat, the more the muscle fibers, tendons, and connective tissue will break down. This is especially true of the legs and thighs. With breasts, the trick is to not overcook them. Keep them to a medium doneness at the most to avoid chewy meat.

Unlike other poultry, duck meat is edible—and, in fact, preferred—at a medium to medium rare internal temperature. If you’re searing or roasting duck breasts, keep a meat thermometer handy and use it on the thickest part of the meat to determine the temperature.

If the interior of a duck breast is cooked to 130 degrees F, it has achieved medium-rare and you can pull it from the heat source. Carryover heat, or the heat still trapped in the meat after it leaves the heat source, will continue to raise the internal temperature even once it’s off the hot pan.

Read Next: How to Hunt Ducks

Final Thoughts on How to Cook Duck

Wilkins firmly believes that wild waterfowl are underrated table fare. Knowing how to cook duck in a way that plays up the robust flavor of the meat makes all the difference. Also remember that not all ducks taste the same. Some of the fishier diver species are best utilized in sausage recipes or brined, fried, and dunked in hot sauce.

“Ducks are weird, man,” Wilkins says. “They ride the line between sky, ground, and water. They exist in this in-between.”

When it comes time to chef up your next limit of mallards, experiment with using the whole bird.

“There seems to be a [new] interest in whole-bird utilization. We’re just trying to get the most out of the bird,” Wilkins says. “Waterfowling is a gear-intensive pursuit. There are a lot of costs associated with it—waders and guns, shells, decoys. People put a lot of effort into it on the front end, and then it seems like there’s not that effort on the back end. Like people don’t have time to pluck a duck, or they don’t cook the meat. I think people are starting to realize there’s a real hypocrisy in that. And of course, this is all stuff that ‘country people’ have always done. But it seems like there’s a bit more of a cultural acknowledgement within the hunting space that we have a responsibility to do better.”