When I checked-in the mid-morning longbeard I killed last week, Indiana’s online system had lots of questions. Did I kill the bird on federal, state, or private land? What was the date and time of kill? Did I shoot a bearded hen, jake, or mature tom? Had I used a bow or shotgun?

One question the DNR didn’t ask, however, was how I’d managed to get close enough to kill that turkey. There was no “Tactic” field with a dropdown menu, no instructions to select one of the following: Calling, Decoys, Spot-and-Stalk, Reaping, Dumb Luck. (Disclaimer: I have killed turkeys using each strategy.)

Read Next: The Case for Banning Reaping and Fanning Turkeys

I’m also willing to bet that most, if not all, state agencies don’t ask about tactics during their own check-ins or hunter surveys. Partly because I’ve hunted turkeys from Nebraska to Florida and I’ve never yet been asked. And partly because there’s no published data on how those tactics correlate to turkey harvest. Because when it comes to wild turkey management, it has never mattered how a legal hunter kills one. It only matters if they kill one.

Declining Wild Turkey Populations

Unless you’ve been lucky enough to live in an area where turkey populations are stable or increasing (yes, they exist), you might’ve noticed that turkey numbers are declining in parts of the country. Most notably, this is occurring in the Southeast. There are lots of reasons turkey biologists say this could be happening. Habitat loss is a huge one. Predation is another. Disease and weather are also big contenders.

What most biologists aren’t saying, though, is that turkey hunters have gotten too good at hunting. (In recent years, we’ve even been complaining that turkeys have become call-shy, which means we might be getting worse at killing turkeys.) Many hunters, though, say reaping is to blame for ailing turkey numbers. Reaping is simply too effective, say detractors, and it’s why states like Tennessee are seeing turkey numbers slide.

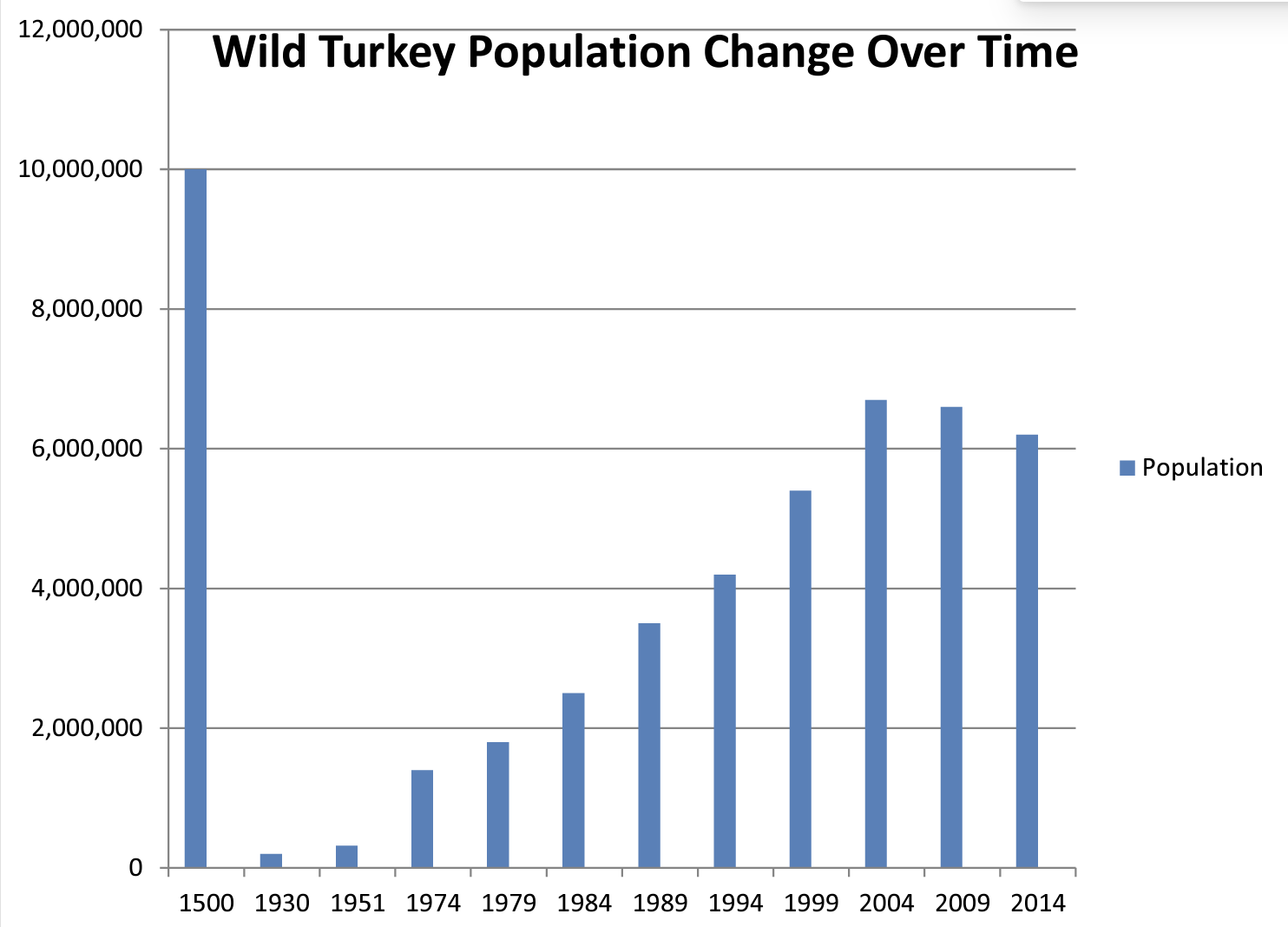

And I get their point: If you’ve been successfully calling in and killing birds during the heyday of turkey hunting, I can see how a new, effective tactic can feel like a real threat. The national turkey population peaked in 2004 at 6.6 to 6.9 million wild turkeys. Almost two decades later, we’ve got an estimated 6 million turkeys on the landscape.

First, the good news: Six million turkeys is still a lot of turkeys, says Dr. Mark Hatfield, a wildlife biologist and the national director of conservation services for the National Wild Turkey Federation.

“Is there something going on with wild turkeys and the health of the overall population? Yes. But are turkeys doing well? Yes. It’s not a sky-is-falling scenario,” says Hatfield. “We just need to understand how we manage turkeys in a post-restoration era … We can’t expect turkey populations to go up constantly. This may be a natural process that we’re experiencing now. We may see fluctuations within populations in cycles. And that’s okay. Is it something we’re comfortable with as hunters? Maybe not. Is it something we see in other wildlife populations? Yes.”

Here’s the bad news for anyone who thinks banning reaping will help stabilize or boost turkey numbers: It won’t.

Reaping Isn’t Fanning (and Neither Are Magic Tricks)

Let’s cover some definitions. When turkey hunters talk about “reaping,” we’re talking about the tactic that involves hiding behind a real or imitation tail fan, or a portable gobbler decoy, to sneak within shooting range of a legal turkey. (As always, even where legal, reaping on public land or in the timber is a bad idea.)

The word “reaping” itself is a misnomer, and partly why the tactic gets a bad rap. It implies a nearly guaranteed outcome: There’s a whole crop of turkeys out there, just waiting to be cut down like ripe wheat. Simply grab a fan and waltz right up to any old tom—if he doesn’t run to you first. You’re sure to kill him.

Except it doesn’t always work like that. Yes, reaping can be effective. So can calling a tom off the roost and shooting him in the wattle two minutes after he flies down.

Just like many hunting tactics, reaping is subject to failure and requires plenty of work. If you’ve ever seen a big longbeard blanch at the sight of a strutter deke and scuttle back the way he came, then you know the same outcome is possible when you show him a fan. Or maybe you’ve spent an hour crawling through a pasture of steaming cow pies toward a strutting longbeard that always stays 200 yards ahead of you; eventually he drifts into the woods with his hens or buddies and out of sight.

Many critics say a fan allows hunters to pick off dominant toms while scaring away sub-dominant toms. I have seen everything from jakes to 4-year-old toms run toward a fan, away from a fan, or ignore it altogether. You cannot predict how a turkey will react to a fan. Turkeys are unpredictable by nature.

Another important distinction: Fanning is not the same thing as reaping. I almost always bring a fan with me when I hunt private land. Not because I plan to dive into the weeds and army crawl after the first tom I find, but because it’s another tool in my turkey vest that may or may not help me kill a bird. I rarely use that fan. When I do, it’s usually in conjunction with a mouth call.

Here’s an example: I once convinced a hung-up longbeard to commit by raising my fan and rotating it slightly. He walked from 60 to 25 yards into my decoys. Other turkey hunters might’ve happily shot the tom at that initial distance; I prefer to kill turkeys at close range. The fan simply helped me make what many traditional turkey hunters would call a more ethical shot.

Flashing a fan with few soft yelps has also saved me from getting busted by hens that pop up too close, or kept deer from stomping and blowing at me for too long. I’ve screwed up stalks, too, just as I’ve screwed up plenty of traditional setups. Hell, I once crawled 200-plus yards across the prairie and shot a henned-up tom without a fan.

There are lots of ways to kill a turkey that require tools (decoys, fans), skill (calling, sneaking), hard work, patience, and luck. Teasing out a particular combination of those, then banning it because it’s not a textbook way to kill a tom misses one of the real reasons we all love to turkey hunt: It should be fun. And reaping, when I do occasionally choose to do so, can be an exhausting, exhilarating, adrenaline-spiking, freaking fun way to kill a wild turkey.

We Have No Data on Reaping, So Let’s Look at Hunter Success Rates

When it comes to setting hunting regulations, we hunters talk a big talk about relying only on scientific management to govern hunting seasons. There’s no room for emotions or hunches when it comes to wildlife management, we tell the non-hunting public. Follow the science. And when it comes to reaping turkeys, we don’t yet have any.

“To think that we have the millions of turkey hunters out there conducting and utilizing fanning is probably a poor assumption,” says Hatfield. “It’s probably a very small segment because they’re comfortable with it, and they may be in a situation that makes them feel comfortable in it. We don’t know how many people are using it. We see it. But how prevalent it is on the landscape probably needs to be looked at.”

The biologists I spoke with say they’re unaware of any data about reaping. I haven’t been able to find any stats while digging around online either. So let’s look at the numbers we do have: annual turkey harvests.

If reaping is as effective and problematic as opponents say, then we would expect hunter success rates to go up in states where it’s legal. I’m not talking about the number of birds killed each spring, which is most often a factor of how many hunters go turkey hunting. I’m talking about the percent of spring turkey hunters who are killing birds. Let’s look at a few examples.

Nebraska

Reaping is typically done on private land in open country, so you might expect a Great Plains state like Nebraska to see an increase in turkey hunter success rates in the years since outdoor TV and social media popularized reaping. The state has little public land and lots of grassland, ag, and riverbottom habitat, which makes it a prime state for belly-crawling turkey reapers to go wild. So hunter success rates should be sky rocketing there, right?

Except they’re not. Turkey harvest success rates in Nebraska have been declining for about 10 years now, from a peak of at least 65 percent, says Luke Meduna, the big game program manager for Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. (Turkeys are considered big game in the state.) Turkey success rates in Nebraska have always been high, he adds, hovering somewhere around 20 points above other states.

“I wouldn’t look at reaping and go, ‘Oh if we get rid of that, it will fix our issues.’ There’s a whole host of other things that are much more obvious that are going on with birds than that hunting technique,” says Meduna, citing factors like low fur prices and changing understories as culprits in the state’s turkey declines. “By comparison to a lot of the Southeast, we’ve fared better in both our harvest and our overall turkey numbers.”

Conclusion: Reaping is legal in Nebraska. Hunter success rates are still declining.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has more timber and higher hunter-density numbers than Nebraska. In Pennsylvania, reaping, fanning, and stalking turkeys is illegal. In fact, any method of turkey hunting besides “hand and mouth calling” has been illegal there since at least 2008, according to old regulations, and likely longer. If you crunch the state’s hunter and harvest numbers, you’ll find that turkey hunter success rates vary. The trend in recent years is clear, however, and it’s declining: There’s been a spring turkey hunter success rate of 24 percent in 2018, 22.2 percent in 2019, 18.1 percent in 2020, and 17.9 percent in 2021.

Conclusion: Reaping is illegal in Pennsylvania. Hunter success rates are still declining.

Tennessee

While reaping is currently legal in Tennessee, there’s a proposed reaping ban on WMAs (a fine idea for public land) and an attempt to ban it statewide. In 2020, the state experienced a record high turkey harvest of 40,105 turkeys taken in spring 2020, during COVID-19 lockdowns.

The Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency responded by adjusting turkey regulations for 2021. TWRA reduced its four-bird bag limit to three statewide. Certain counties with more pronounced declines had a two-bird limit and experienced a delayed season start date. The 64 percent success rate of 2020 declined to 58.8 percent in 2021. While long-term success rates are more telling, those changes corresponded to reduced hunter success—without banning reaping.

Conclusion: Reaping is legal in Tennessee (for now). Hunter success rates declined after season and bag limit changes.

The bottom line? Turkey success rates are declining in states where reaping is both legal and illegal.

Reaping Doesn’t Affect Turkey Biology. Your Season Dates Do

The lever that state wildlife agencies have when it comes to turkey population management, explains Hatfield of the NWTF, is simply the ability to adjust season dates and bag limits.

Hunters who reap turkeys “are still operating within the confines of the state wildlife agency harvest bag limits and fees and structure,” says Hatfield. “So ‘effectiveness’ is: If you can harvest two wild turkeys, and you harvest two wild turkeys, that’s still the same number. The methodology [of how you harvest them] is not going to drive population-scale changes.”

Hatfield says it’s not so much a question of what time of day you kill a longbeard, but the timing of your state’s season. Wild turkeys typically have a brief breeding period, and because states have always tried to expand turkey hunting opportunities, we have opened seasons earlier and earlier—thus encroaching on that breeding period. Ideally hens should be on their nests by the time turkey hunters hit the woods.

“If we have turkey seasons set too early, are we disrupting their natural breeding pattern? I think that’s probably the question we need to evaluate,” says Hatfield. “Because we’ve always been out there chasing birds, calling to birds, and basically disturbing them. But as seasons have crept earlier and earlier, have we now gone too early? And do we need to revert to a more biologically set season, versus a socially set one?”

Recent research shows that breeding and nesting times are spreading out across the season in response to general hunting pressure, renowned turkey biologist Dr. Mike Chamberlain explained in a recent interview with Realtree. Rather than regulate the different ways we turkey hunters are disturbing birds, certain states are simply pushing back season dates to alleviate hunter pressure when peak breeding traditionally takes place.

Changes in Turkey Hunting Tech Aren’t Limited to Reaping

In the years since turkey numbers peaked, we’ve grown used to all kinds of technological developments in turkey hunting. We use powerful mapping apps like onX Hunt, which have helped hunters access more (and sometimes previously untapped) turkey hunting ground. Shotshell technology has boomed, with more hunters making lethal shots at much farther distances than even five years ago. Crossbows are much more common in archery turkey seasons. And turkey decoys are more lifelike than ever. So why are critics picking on reaping?

“Everyone’s got their own ethics. You might say, ‘It may not be for me,’ but that doesn’t necessarily mean it needs to be illegal,” says Meduna of Nebraska Game and Parks, who is concerned with wild turkey habitat rather than hunter methods.

To single out reaping at the exclusion of other innovations that have expanded opportunities for hunters to kill turkeys that “might not have otherwise been killed,” reveals an inherent bias against the tactic itself—not any true impact on turkey populations.

“If we went back to 25, 30 years ago when decoys really started to come into play, there was probably a very similar concern” to what we’re experiencing now with reaping, says Hatfield. “As new methods come online, we have to monitor their effectiveness and look at their safety.”

And to those who say, well at least banning reaping can’t hurt turkey numbers, that’s also a troubling assumption. Anytime you over-regulate or outright ban a method of hunting, you risk losing hunters. Why jeopardize the participation (and license dollars) of younger or newer hunters who might be able to kill a turkey by stalking it simply because it’s not traditional? Who’s to say reaping one bird won’t lead to a lifelong love of turkey calling? Even if you disagree with the push to bring new license-buying hunters into the fold, we can at least agree that turkey hunters have the biggest stake in a healthy turkey population.

“We should continue to look at this in a balanced manner,” says Hatfield, who cautions against divisiveness within the hunting community. “It’s not going to be one harvest structure, one hunting technique, or one outlook [that changes turkey populations]. We have to continue to keep an open mind and we have to continue to provide social support and social license for the wildlife agencies to adjust season structure and bag limits as appropriate based on biological information—not on public opinion.”

By social support, Hatfield means weighing in when your state agency asks for public comment, and not dismissing recommended season changes just because they don’t fit your schedule or calling gobblers seems more difficult. The real issue at the heart of the reaping debate isn’t a scientific one, but a social one. Resistance to a few new tactics or technology because we long for the good ol’ days of restoration-era turkey hunting won’t help us adapt to our present management challenges.