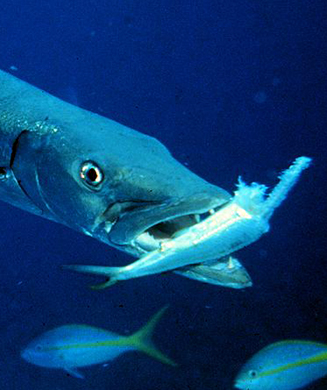

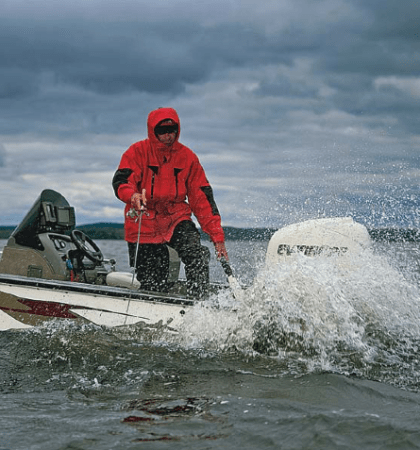

We’d suffered through eight hours with zero bites. Eight whole hours of watching balloons bob around in the swells, inhaling chum fumes, and roasting in the July sun. This is shark fishing, and when nothing’s happening, it can be a painful experience. At 5 p.m., I said “uncle,” and we started reeling in the lines. My friend Darren was cranking the short corner at a steady clip when he suddenly yelled out, “oh shit! Here we go!” A mako came screaming in behind the bluefish carcass being pulled along the surface. It sucked up the bait in a blink, Darren flipped the reel to “strike,” and the 150 pounder went airborne 10 feet behind my outboard. We were only 12 miles offshore looking to play catch-and-release with some brown and dusky sharks. A shot at a mako never crossed our minds, but there it was in all its glory, cartwheeling and ripping drag. Of all the fish that had been hooked on my boat, this one gave me the biggest adrenaline rush.

That was 10 years ago, but I think about that mako often. Not because we won that battle, but because we lost. We were feet away from sinking the flying gaff when it gave a headshake and severed the 100-pound fluorocarbon leader. We were so devastated that nobody spoke on the ride in. During the entire fight, I could taste the grilled mako steaks. I could see the mounted jaw set hanging in my office. I knew then that I may never get another shot at a mako on my boat given its limited range. I was right. In several more years of shark dabbling, I never hooked another mako. And as of July 5, 2022, nobody on the East Coast can hook another mako for the foreseeable future.

Shortfin Mako Shark Fishing Ban

The federal government has officially declared Atlantic shortfin makos overfished, prompting the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to enact a ban on landing or keeping them. There is no argument about the declaration being correct. Sharks are one of the most—if not the most—pressured species in our oceans. Illegal shark finning operations the world over have taken a severe toll. Factor in climate change and pollution (which NOAA also attributes to the mako decline), and you can see how you go from fishermen in the 1980s bringing in an estimated 1 million pounds of mako per year to less than 80,000 pounds in 2020. This ban is aimed at giving these slow-growing fish time to rebound and recover, and I very much hope it achieves that goal. But right now, there is no set end date for the ban.

Can a Fishing Ban Create a Rebound?

Recently, Florida approved a limited harvest on goliath grouper, a species that was fished to the brink of extinction. The ban on this fishery, did, in fact, result in a rebound. The rub is that it took 32 years for them to bounce back enough for the regulations to change. I can’t help but wonder if makos will follow a similar timeline. The funny part is that I believe this mako ban is absolutely necessary to save them, but that doesn’t take away the sting of knowing that harvesting a mako is completely off the table for the foreseeable future. Believe it or not, I wouldn’t feel the same way if I’d landed that fish on my boat all those years ago.

Read Next: Florida Moves to Officially Lift 32-Year Ban on Goliath Grouper Fishery

Prior to the hook up on my rig, I’d been present for three mako harvests, and I wasn’t the rod man for any of them. For someone like me who, at best, might be in a position to take a mako once every two or three years, it’s easy to talk yourself into being righteous. I never wanted an office full of jaw sets, after all, but dammit I did want one. Just one. Unfortunately, when numbers get as low as they are right now for these sharks, conservation measures are typically drastic. And this step certainly feels drastic, especially when you consider that East Coast anglers have had mako fever for decades.

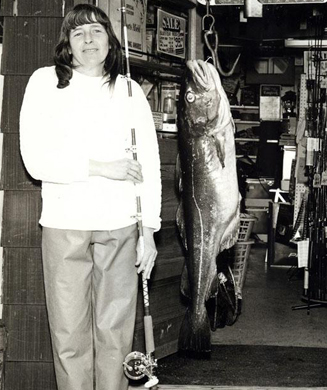

Mako Fever

As a little kid, I flipped through Pete Barrett’s book Fishing For Sharks daily. I pretended my rubber sharks were makos when I couch fished. Up and down the coast there were dozens of high dollar mako tournaments held every summer. Every tackle shop sold at least one mako T-shirt. When someone hung one of these fish at the dock where we kept our family boat, the crowds would gather. I would look at those sharks, idolize the captains, and think “someday.” Makos in many ways were as symbolic of Northeast offshore fishing as striped bass are of inshore fishing.

The reality, however, is that Northeast mako fever has already been breaking for a while. Tournaments were dwindling rapidly, and most of the dedicated mako hunters I knew stopped targeting them years ago simply because it wasn’t worth spending the money on fuel, bait, and chum. Harvesting a mako was a long shot because not only did you have to hook one, you had to hook a legal one. (Before the closure, that meant one male at least 71 inches or one female at least 83 inches). Still, it’s hard to imagine makos not being incorporated into the big Northeast offshore three—tuna and white marlin being the other most coveted targets.

It wasn’t that long ago when West Coast anglers had the mako fever as bad as the east siders. It took years of conservation messaging and studies to shift the mindset. The perspective on mako fishing was eventually altered so drastically that friends in California have told me if you hang a mako at the dock now, nobody cheers—you’re a pariah. This, mind you, is in a state with a strong mako population that still allows anglers to kill two fish a day with no size limit.

We’re not quite there yet on the East Coast, and I’d argue that the downturn in mako fishing has less to do with conservation right now and more to do with cost effectiveness. West Coast makos live within the range of small boats (hence the popularity of fly fishing for them), but getting to where they lurk in the East requires a larger boat, longer runs, more time, and more money. This makes it unlikely that a strictly catch-and-release fishery will ever achieve the same popularity. But if this ban works, perhaps in five or ten years, stronger numbers will put more makos closer to shore for a new generation of anglers who didn’t grow up during the mako fever era. Maybe this new group will already be accustomed to protecting sharks. And maybe those numbers will eventually get strong enough to prompt a tag lottery like Florida has implemented for goliath grouper. It could be a long shot, but I’d like to think that someday I’ll get to take my one. Just one.