Tender boats. Layout skiffs. Big water. Hundreds of decoys. It takes a ton of equipment and intense effort to successfully hunt the diving ducks of sporting legend, right?

Not when you target ringbills. Of all the diving ducks, ringbills (also called ring-necked ducks or blackjacks) have the strongest affinity for small water. In fact, hunting ringbills often looks more like puddle-duck hunting than diver hunting.

Success on these fast-flying divers starts with understanding their habitat preferences, then adjusting your setup accordingly.

Meet the Puddle Diver

The ringbill is a first cousin to the bluebill but has a blacker back and whiter belly, yellow eyes, and a distinctive slate-gray bill edged in white and adorned with a white ring. Hens have a brown back and white belly, and a white bill ring as well.

Ringbills behave more like puddle ducks than divers, feeding on tubers, seeds, leaves, and plants in 1 to 3 feet of water. That’s deeper than mallards, and shallower than bluebills and redheads. This in-between niche brings ringbills into range—both economic and shotgun—of the average duck hunter with only waders, decoys, and a small boat at his disposal.

Ringbills push south ahead of the big rafts of other diving ducks. These small-water birds arrive well before northern mallards, when the weather is just starting to get a little raw and autumn’s leaves are just beginning to drop, but well before small water freezes up. Ringbills don’t like icy conditions. Most of these birds migrate to the Gulf Coast, most notably in Florida.

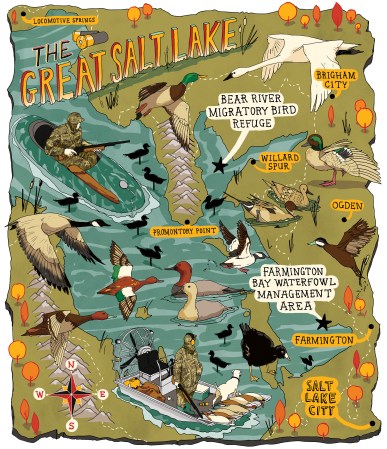

Find ringbills on marshes, swamps, bogs, sloughs, ponds, and backwoods potholes. Think wood duck habitat. Ringbills are comfortable around timber because they nest near shallow boreal waters. But you’ll find ringbills in open country, too. Each year I shoot them from pine-rimmed wetlands in Wisconsin and Minnesota, and in cattail-lined puddles in the Dakotas.

Read Next: How to Call Diving Ducks

The Setup

Ringbill setups should be pretty simple. Start with a half dozen mallard decoys, because ringbills feel right at home with greenheads. Then add diver decoys—18 or so is plenty. Ringbill decoys are best, but bluebills work fine too; it’s the visibility of the drake’s white that you’re after. If you don’t want to invest in a spread of 18 new diver dekes, simply buy some used mallard decoys (check Craigslist for deals) and paint them matte black with white sides.

Set up with the wind at your back, a knot of mallards in front, and a V of diver decoys extending out and inviting ducks into the pocket. If the wind is coming from the side, shorten your pattern to a C and rotate it so the opening of the C faces downwind.

Mallard calls will get ringbills’ attention, but let the decoys do most of the work. You can also growl or purr lightly on a diver call (there are a variety on the market) if you feel compelled to call the ducks in.

Heavy loads packed with size No. 2 or No. 3 steel are about right. Ringbills are on the small side, but they are densely feathered and carry a thick layer of greasy fat under the skin. These speedy fliers can be tough to drop, and you don’t want crippled birds diving to escape.

Once in hand, a drake ringbill rivals any other diver for good looks, and is equally delightful to eat.