We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

Just as the lever-action .30/30 is iconic in the North American whitetail woods, certain rifles and cartridges are African safari icons. But which are they? Which define the long, rich tapestry of safari hunting on our greatest big-game continent?

A surprising many.

The surprise is as much the variety of calibers and cartridges as the makes and models of rifles. Seen through the lens of the modern safari hunter, classic Africa rifles would all seem a tight knit family of side-by-side doubles and beefy bolt-actions with oversized holes at their muzzles. That is only partially true.

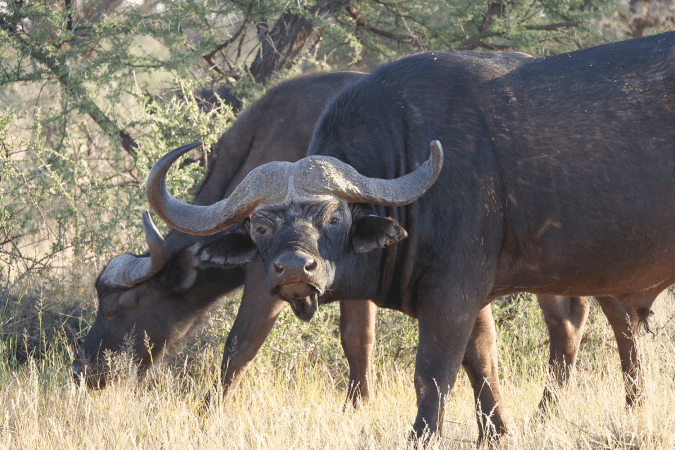

The double-barrel big bores evolved from double-barrel muzzleloading shotguns first used to slow down large and cantankerous animals. A .50-caliber Hawken might have sufficed for a Rocky Mountain fur trapper and even a bison market hunter. But not an ivory hunter. Or even a voortrekker in pursuit of Cape buffalo or cameleopard (giraffe) skins. Even when firing 1/4-pound balls from 4-gauge guns, hunters usually needed multiple hits to bring prey to the ground. The process of reloading a muzzle loader, of course, meant one hired a gun bearer or two to stay at heel with backup guns loaded and ready. The second barrel of a side-by-side double was often the last line of defense.

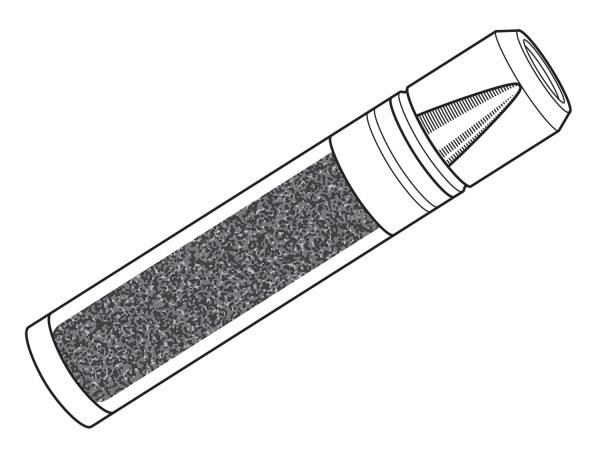

Hardened and elongated bullets (Maxi balls) improved terminal performance in the mid-1800s, but the real leap forward came in the 1890s with the advent of smokeless powder. The concentrated energy of nitroglycerine boosted velocities significantly. Doubling bullet mass doubles energy. Doubling velocity quadruples energy. This made lighter bullets more effective. Nevertheless, tradition dies hard. So do buffalo. Bore diameters certainly shrank during the 1890s and 1900s, but they seemed to settle between .40 inches and .577 inches.

Oddly and simultaneously, a few hunters, tired of massive recoil and heavy guns, began experimenting with lighter military rifles and cartridges. The most famous and influential was W.D.M. “Karamojo” Bell. This Scottish ivory hunter proved a puny .275 Rigby Mauser moving round nose, 173-grain FMJ military bullets 2,300 fps (feet per second) killed mature elephants and buffalo as effectively as bigger bores when bullets from both were applied to the same vital places (brain and heart.) The .275 Rigby is the 7×57 Mauser with a different name.

Heavy Calibers for Dangerous Game

Despite Bell’s success, African dangerous game cartridges settled firmly in the larger bore sizes starting with the minimum .375 H&H Magnum and running through such famous numbers as .416 Rigby, .425 Westley Richards, .404 Jefferey, .450 Nitro Express, .470 Nitro Express, .500 Nitro Express, and .577 Nitro Express, among others. The rimmed cartridges were engineered for best function in double rifles, which still cling to their romantic position because of their second shot speed and reliability. All spit bullets weighing anywhere from 300 grains to 570 grains at muzzle velocities from 1,900 fps to 2,600 fps with most settling in at about 2,100 fps. This is a sufficient speed and mass to generate anywhere from 4,000 to 5,800 foot pounds (ft-lbs) of kinetic energy.

For perspective, the .30-06 with a 180-grain slug might hit 3,000 ft-lbs. Only one .60-caliber was ever marketed, the .600 Nitro Express, throwing 900-grain bullets about 1,900 fps to generate an unbelievable 7,000 ft-lbs muzzle energy. Even burly, beefy professional hunters considered this a bit excessive, best employed in the most dire emergencies only. The 16-pound rifles also limited how far PHs and hunters were willing to carry it.

The Move to Double Rifles

Strong, fast, naturally pointing doubles from Holland & Holland, Rigby, Westley Richards, Boss, Purdey, William Evans, Boswell, and other boutique English gunmakers gave and continue to give professional hunters and wealthy clients the tools and assurance they need in the face of a 1,500-pound buffalo at terminal velocity.

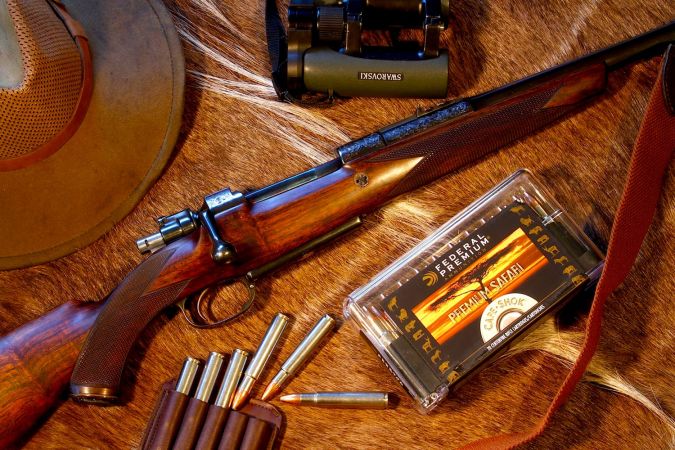

But there is a fly in the double rifle ointment. Expense. Many, if not most doubles, with articulating triggers and intercepter sears cost five to ten times more than a bolt-action of similar quality. This focuses the attentions of average hunters, even professional guides and PHs, on controlled-round-feed bolt actions like Bell’s Rigby Mauser M98. This controlled-round-feed magazine rifle provides four or five quick shots with remarkably reliable function. It wormed its way into the batteries of professional hunters when magnum versions came chambered in .416 Rigby, .404 Jeffery, .425 Westley Richards, .450 Rigby, and .505 Gibbs.

The Rigby Mauser was the standard bolt-action big bore in Africa until Teddy Roosevelt and Stewart Edward White carried Griffin & Howe modified 1903 Springfields on safari prior to WWI. They and others proved that the .30-06 could handle leopards, lions, even buffalo and rhino. Then, in 1956, the affordable Winchester M70 CRF bolt-action came along in .458 Win. Mag. This round throws 500-grain bullets to within 250 ft-lbs of the .470 Nitro Express’ energy levels. Dozens of PHs adopted it. The CZ 550 bolt-action is another rugged, dependable CRF, as is the superb, high-end Dakota M76.

The .375 H&H is Just Right

The most common chambering among African bolt-actions is the .375 H&H, one of our first belted magnum cartridges. Ever since its introduction by Holland & Holland in 1912, the old .375 H&H has clung to its well-earned fame because it’s a Goldilocks round. Not too big, not too light. Just right for the sport hunter with insufficient time to become proficient with heavier recoiling rounds. It may not be the equal of the .458 Lott (a stretched .458 Win. Mag.) or .505 Gibbs for stopping a charge, but the sport hunting client is always backed up by a professional PH. Loaded with 235-grain bullets going 2,800 fps gives the .375 H&H 300-yard reach for smaller antelope while 270-grain spire points make it a trajectory match for a .30-06 shooting 180-grain spire points. Step up to full-house 300-grain loads and with 4,100 ft-lbs muzzle energy you enjoy sufficient energy for not just eland, lion, and leopard, but rhino, buffalo, elephant, and hippo on land.

Read Next: How to Plan a Hunting Trip to Africa

Bolt Guns vs. Double Barrels vs. Single-Shot

The most significant feature of the Mauser 98 and its near copies that cement them as safari ideals is their massive, leaf-spring, claw extractor that grabs rounds from the magazine, holds them firmly against the bolt face for a straight, unencumbered ride into the chamber, and yanks them out with a wide, firm grip. Additionally, bolt-actions are much more precise for long shots and can be easily fitted with quick-release scopes for additional precision, something needed for many plains antelope. In contrast, double rifles are at their best inside 50 yards, the distance at which most are regulated to print near the same point. You can’t free-float a double’s barrels, and getting both the throw bullets to the same spot is a slow, expensive process.

One surprise safari classic is the falling block single-shot. More than a few African hunters worked with the old Winchester M85 single-shot with its external hammer, but the most famous falling block is the Farquharson as built by Gibbs. Few were actually made, but Frederick Selous used one, and that accrued to its fame. Today, the Ruger No. 1 is the go-to falling block for Africa. More elegant and expensive is the superb Dakota Model 10. Of course, a single-shot is not ideal for dangerous game, but, again, the PH is at hand to stop a charge. Knowing you have but one shot tends to focus your attention on making it a good one.

Despite more than a century of these doubles, CRF bolt-actions, and single-shots, modern safari hunters are broadening the category to include push-feed bolt-actions and even lever-actions. The same rifles hired for elk, moose, and mule deer in the U.S. are proving just as effective for kudu, oryx, and even buffalo in Africa. I’ve personally used multiple CRF and push-feed bolt actions chambered for everything from .223 Rem. to .450 Lott during some 15 African safaris and suffered no ill effects but a poor trigger and a dropped magazine from any. Lever-actions in traditional chamberings like .45-70 Govt., .405 Win. and newer magnums like the .475 Turnbull are turning heads in African safari camps these days. This hardly makes lever-actions or push-feed bolt-actions safari classics, but they can certainly do the job.

Shooting Small Ammo

Finally, we’d be remiss if we ignored the long history of small caliber rounds in Africa. While some consider Bell’s .275 Rigby an exception to the big bore rule, in reality most African game has probably been taken by such small bores. Since the early 1800s local farmers, ranchers, meat and hide hunters have made do and done well with a wide variety of affordable, often military surplus rifles and ammo. In addition to the 7×57 and .30-06, the .303 British, 6.5×55 Swede, 6.5 Mannlicher-Schoenauer, 8mm Mauser, and 9.3×64 Brenneke were quite common across Africa. Many are still collecting biltong, increasingly joined by 7mm and .300 magnums, .308 Win., 7mm-08 Rem., .270 Win., and even the loved/hated 6.5 Creedmoor.

Read Next: 10 Life-Changing Lessons I Learned From My First Africa Safari

The point is, any good shot with a good bullet can use virtually any rifle/cartridge effectively on appropriate African game. But when campfires glow against dark African nights, the appeal of the classics dominates hunters’ dreams and conversations. And the most recognized and venerated of all is the controlled-round-feed bolt-action chambered .375 H&H Magnum.