THE SOUND OF the drops hitting my rain jacket seemed to echo in my ears as I sat against the soggy oak tree, the lightweight sycamore-and-marblewood recurve resting in my lap, my arrow fletchings laden with water.

The weather matched my mood. My first year as a traditional bowhunter had fallen far short of my expectations. I had never really been a fan of deer hunting in the rain, and after an hour in the misty downfall, I considered calling it quits and heading back to my truck. But this late in the season, that would feel too much like giving up on the whole thing rather than on just one hunt. So I resolved to stick it out a little longer, absorbed in my thoughts and feeling as gray as the sky above me.

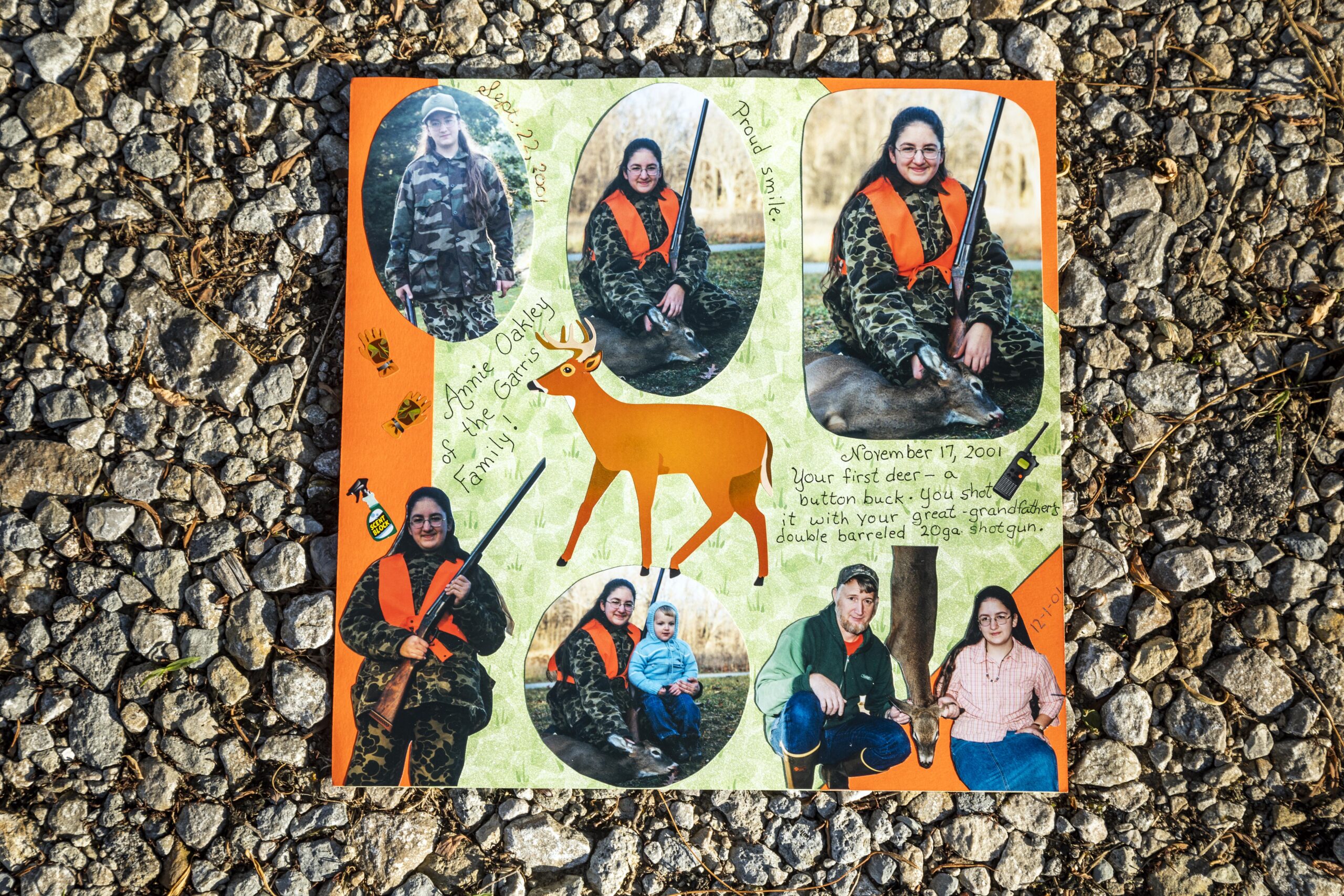

Family Ties

I’m not new to hunting, or even to bowhunting. My five brothers and three sisters and I grew up running barefoot through the woods and shooting our bows in the empty hayloft of the barn. In winter, we hunted whitetails with three hand-me-down shotguns between us. Traditional bowhunting didn’t come until much later. I was sitting in my treestand at the ripe old age of 26 when the thought struck.

I had just shot a big doe, threading my arrow perfectly between two trees and through both her lungs. As I watched her bounce off, tail bright against the fading light of day, I realized it had felt too easy. That excitement that had driven me to bowhunt hard for the past 10 years—the heart-pounding rush that always came with shooting a deer—seemed to have diminished in that moment. And I felt a sudden longing for something more. I had devoted myself for a decade to becoming the best bowhunter I could be; to have that drive suddenly disappear was a blow.

I needed a challenge. And switching to a trad bow seemed plenty challenging. Truthfully, it had been in the back of my mind for years. Traditional archery had always been interesting to me, as if somehow there were a bigger purpose to it. Recurve and longbow hunters always seemed to have a larger-than-life way about them. They were accomplished and skilled in a way that I wasn’t. For years I had put off learning to shoot a traditional bow because it looked hard. I hadn’t shot one since I was 8 years old, and back then I was hardly accurate. But as I sat there in my treestand, vexed in the aftermath of a perfect hunt, it finally felt right to pick it up again.

Starting from Scratch

The trouble was, I didn’t know anyone who hunted with one. I knew that my dad had begun bowhunting with a recurve. But I lived in Ohio now, and my dad still lived in New Jersey. The 600 miles between us meant no backyard lessons this time around.

Instead, I dove into my own research, poring over YouTube and trad articles, reading stories of Fred Bear. I had grown up with these tales of the legendary bowhunter, one of my dad’s heroes. Dad would tell us about him, including how he’d met the man once and received a signed photograph. If my dad looked up to Bear, he was surely someone to study.

To apply all these lessons, I needed a bow. After even more research, I reached out to a bowyer at Wolf Paw Custom Bows. I wanted to make sure I bought one that was built for my draw length, and whose 40 pounds (Ohio’s minimum for bowhunting) I could pull. This may not seem like a lot of weight to draw, and it’s not for a compound—mine was set at 60 pounds. But compounds have the luxury of let-off, which helps you hold your bow at full draw; traditional bows are a different beast. You must hold the bow’s full weight as your arrow tries to leap off the string.

The bow I ended up with was a custom hybrid recurve. The limbs looked more like a longbow’s, with less height than you normally see on a recurve. I could easily draw it, and it shot like a dream. I spent hours in my backyard, trying to figure out how to become even competent. I had been seeking a challenge, and I had found one.

Some days I shot beautifully. Some days I could barely hit the target. It was so frustrating because it seemed as if it should be so simple. There were no sights, levels, or kisser buttons, just a stick and a string. The days when I shot badly, I would hear my dad’s voice telling me to put the bow down and take a break. Come back with a better mindset and a clean slate. So I did.

The day I realized I was the deciding factor in my success, everything changed. Shooting over and over with the same equipment and without consistent results could only mean I was the problem. This is both the downfall and the beauty of traditional archery. If you mess up, it’s your fault. Yet when you excel, it’s also because of you. There are so many variables in a shot with a compound bow. With a traditional bow, there’s just one.

Hard Truths

I shot countless arrows and studied hard but still didn’t feel proficient. There are many ways to shoot a traditional bow accurately. After weeks of experimenting, I finally just decided to shoot instinctively. It felt the most natural after years of bowfishing.

I started with the goal of taking a whitetail with my recurve, and six months of dedicated practice later, I knew the time had come. I would never know if I was good enough to kill a deer with my new bow if I didn’t go into the woods and try.

I’d guessed that learning to shoot a traditional bow would be tough, but I figured hunting with one would be similar to hunting with a compound, and perhaps not too difficult. I was dead wrong.

Hunting with a traditional bow is all about your mindset. If you go out expecting to fill your tags easily and head home, you’re likely in for disappointment. You’d better make peace with the fact that the only things you’re taking home most days are memories to look back on and a tag in your pocket. If this isn’t something you can get behind, then hunting with a stick and string isn’t for you.

I learned this the hard way. I started that first season as a trad hunter with plans to hunt primarily from the ground. I had shot from stands with my new bow, yet I didn’t feel as comfortable there as I did with my compound. Ground hunting seemed to be the more traditional method anyway, as that’s what most Fred Bear stories were about. And so that’s where I hunted. My first day in the woods was as uneventful as many archery openers are: I didn’t see a single deer, but it felt good to hunt after so many months of buildup.

Related: Newsflash: Women Have Been Hunters as Long as Hunting Has Existed

As the weeks stretched on, it didn’t feel quite so good. Southern Ohio’s sticky early season turned into a frosty November, and I still hadn’t found the opportunity to shoot a deer. I had seen many—forkhorns, last year’s fawns, fat does on high alert. Yet none offered what I considered a perfect shot, that shot I felt confident about. Nothing but the shot I was picturing would do. Everything needed to line up, because messing up was out of the question.

I have always been stubborn. I remember when I was 15 and had one last muzzleloader tag to fill. There were only a few days left in the season and I hunted every day, morning and night, in subzero temperatures. My hot chocolate would be frozen in my thermos before I even got to my treestand, lungs burning from walking through knee-deep snow. Every day my mom would tell me to stay inside, and every day I would keep hunting. I ended up with frostbite in all 10 of my fingers that season. But I filled that last tag.

That same stubbornness kept me in the woods my first trad season. The more days that passed without a filled tag, the more determined I became. I can do this, I kept reminding myself. I know I can.

Chilly November turned into a bitter December. Every opportunity I had, every day I didn’t work, I was in the woods. I would practice as much as I could, partly to keep up my confidence and partly because it had been instilled in me that practice is key. I could still hear my dad reciting his rule all those years ago. If you don’t practice, you don’t hunt.

The Tipping Point

Christmas Day arrived unseasonably warm and rainy. My lofty goal of killing a whitetail with a stick bow seemed to be drifting away. The season’s end was just a few weeks off, and the tough conditions of the late season had settled in.

My husband had to work Christmas evening, so our festivities at the in-laws’ ended early. I drove home and sat around the house, watching raindrops fall and arguing with myself about whether it was worth an evening hunt. I have since learned a golden rule in life: If you have time to hunt, go. There are always deer somewhere, no matter the weather or time of day. In a split second, almost before I knew it, I had grabbed my gear and started the truck.

That’s how I ended up against a soggy tree trunk, brooding in the rain despite the holiday. I’d spent all season just like this, my back against rough bark, bow in my lap. Today I was thinking about the hunters before me who had brought home venison with a stick and string: Howard Hill, Fred Bear, even my dad, who had been a traditional bowhunter for years before compounds were invented. I wanted to be like them, even though I couldn’t quite say why. It just felt as if I were meant to.

Even in those slow, agonizing moments, I was scrambling to gather my composure. My bow suddenly felt awkward in my palm as the raindrops ran in rivulets down the riser and onto my leather shooting glove.

I was stewing on all this, how I was failing my heroes and myself, when I saw movement. For a second, I thought perhaps the deer had sprung forth from my thoughts, simply imaginary. But no—there they were, very real, and heading right toward me.

Three deer, all antlerless, were picking their way through the soggy leaves. If they continued on their path, they would pass at 20 yards, and I would have the broadside shot I’d been waiting for all season—if they came my way, and if I could get one to stop. I waited, heart pounding, as the seconds crept by. Even in those slow, agonizing moments, I was scrambling to gather my composure. My bow suddenly felt awkward in my palm as the raindrops ran in rivulets down the riser and onto my leather shooting glove. The first two deer changed direction slightly, presenting hard quartering-to shots. I clutched my recurve, my legs starting to go numb in the soft ground where I was kneeling, all my hopes pinned on the third deer.

For some reason still unbeknownst to me, that last doe continued straight on her original path. And then she stopped. She looked back over her shoulder as if another deer were coming, and I drew and released in one smooth motion.

My arrow hit deep behind her shoulder blade. She took off, slipping and sliding in the mud, making a wide trail in the leaves as she ran, blood flowing. It was a good shot. No, a great shot. I sat there shaking, adrenaline coursing through me, my bow back in my lap. I didn’t even feel the rain falling on my face now.

Full Circle

Retrieving the doe that day was quick work. I hadn’t seen her fall, but I knew right where to find her. As I knelt beside her and placed a hand on her fur, I was in awe. Traditional archery was the hardest hunting I’d ever done. But it was also the most rewarding. Kneeling there in the rainy woods on that warm December afternoon, I knew I would never hunt with a compound or a gun again. From here on out I would carry a traditional bow and nothing else.

Most days, traditional bowhunters really are just showing up for the experience. The odds of success are much slimmer with a recurve or longbow, but the hope is stronger. When my arrow slipped behind that doe’s shoulder, every deer I’d ever shot with a gun or a compound suddenly seemed to pale in comparison. The work I’d put into this season had made me appreciate this moment even more. This was how hunting is supposed to be.

Since that first season, I have been successful many times. The experience and the feelings have yet to disappoint. My love for traditional archery has grown, and every season is still a learning experience. It’s not always an easy thing to fill my tags, but I have learned to take joy in the hunt itself more than ever. As each day passes, my path becomes clearer.

Shortly after my first season as a traditional bowhunter, my dad began to express interest in getting back into it. The more I shared my own stories and passion, the more he talked about one of his old bows—a Bear Super Kodiak—and how he missed it.

“I wish I’d never sold it,” he said, not for the first time. “I would love to get back into shooting it.”

Eager to have another traditional bowhunter in my life, I found a Bear Super Kodiak Black Beauty, an exact replica of the one my dad had bought in 1972, and gave it to him. The following fall, he killed two deer with that Super Kodiak. Although we still live hundreds of miles apart, it feels like we’re together when I hear about his hunts or get texts from him in his tree-stand. In a way, I helped put some of the joy back into his own hunts after 40-plus years with a compound.

Two years ago, I started bringing my own daughter into the woods with me, strapped to my back beside my quiver. Isabella was born two years after I took up traditional bowhunting, and I hope to one day pass it on to her. She already has an amazing collection of bows just waiting for her to grow tall and strong enough to draw. But the simplest of them all is the most special: a little red Bear recurve. The shelf handle is well worn from hundreds—thousands—of arrows. The red finish is scratched and the limb tips are beat up. It was my dad’s first bow, a Christmas present when he was 11. Not knowing any better, and without an archer to mentor him, he strung it backward that first year—until one day he saw a picture of Fred Bear and realized how it should be. My dad shot hundreds of arrows at targets and hay bales as a kid, and apparently put a few holes in Grandpa’s garage.

Read Next: Bowhunting with a Recurve, and a Toddler

That little red Bear was my first bow too. My brothers and I spent hours shooting bull’s-eyes tacked to a foam target. And now it’s Isabella’s first bow. It’s not new anymore, but that’s part of its legacy. And it still shoots great.

At just 2 years old, Isabella is still far too young to draw a real bow without help, let alone hunt with one. But she can hunt with me, and she has ever since she was 6 months old. I know that Isabella may decide that she doesn’t want to hunt when she’s older, and, honestly, I’m okay with that. I will never force it on her. She’s already as stubborn as I am, and I know that to truly be a bowhunter, the motivation must be yours alone. But I hold out hope. After all, it’s in her blood.

This story originally ran in the Traditions issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.