Dr. Grant Woods likes to assess the health of Deer Country from three different altitudes: what he calls the “satellite view,” a broad look at macroscopic trends across entire regions; the “helicopter view” that can evaluate conditions on a specific property; and the view from the ground–his “shoelace view”–where he can count animals and inventory forage.

Woods is a consulting wildlife biologist whose land-management work takes him around the nation. And any way he looks at it, from almost any region or perspective, he says America’s deer herd is in trouble.

“I think we’re nearing a crisis mode,” says Dr. Woods, who isn’t given to hyperbole either by profession or personality. “The best-case scenario is that deer populations drop 10 to 25 percent over the next couple years.”

He’s not alone. The director of a Southeastern state game-and-fish agency, who didn’t want us to use his name, notes that biologists in his state are seeing what he calls “pockets of poverty,” whole townships with few deer. A couple of counties away, though, whitetails are above long-term populations.

“I can’t draw conclusions about what’s driving either declines or increases,” he says. “But I’ve personally been telling hunters for 20 years that you can’t kill enough does. Now I’m starting to say maybe it’s time to put on the brakes.”

That downbeat assessment seems inconsistent with a generation of euphoric news about America’s favorite game animal–after all, we’re used to repeating the mantra that the nation’s greatest conservation accomplishment was the restoration of whitetails from the brink of extinction to a current population of more than 20 million. Managed hunting has increased deer populations, expanded hunting opportunity and given rise to an American original: the hunter/conservationist who pays for the opportunity to manage a public resource and who cherishes the very quarry he intends to kill.

But Woods claims a troubling combination of habitat loss, escalating numbers of predators, underfunded wildlife agencies and even hunters’ behavior and expectations are stressing America’s deer herd. And instead of gently declining to a sustainable level, Woods and others are suggesting whitetail populations are poised to experience a steep drop, somewhere between a significant correction and a catastrophic crash.

Before you go out and sell your ground blind and grunt tube, understand that deer are not in decline everywhere, and where they are hurting, some of the maladies are reversible.

But if the slide is as widespread and as steep as Woods predicts, then we could be headed toward a crisis that has the potential to reshape the culture and economy of conservation in America.

“If whitetail populations are off more than 10 percent for a couple of years, then I expect up to 50 percent of our hunters will stop hunting,” predicts Woods. “Sometime over the last generation, hunters became fickle. They’ll participate when opportunity is good, but give them a couple of poor years (of hunting) and they’ll stop buying licenses and gear. They’ll take up golfing instead.”

That sort of talk sends shivers through the hunting community. Whitetails drive the industry, not only in terms of numbers of participants (more than 11 million), but also with the hunting licenses that fund state wildlife agencies (nearly $600 million annually) and the gear we buy ($12.4 billion).

“The whitetail deer is the backbone of the hunting industry in America,” says John L. Morris, founder and owner of Bass Pro Shops. “And not just in the fall, prior to hunting season. In the last decade we’ve seen deer hunters become year-round customers as they develop land and intensively manage their property.”

AGING FORESTS

None of us like reductions in hunting opportunity, but isn’t it true that whitetail numbers have been at historic highs for over a decade? Like the inflated housing market or the “irrational exuberance” of the stock market, maybe we’ve been living in a whitetail bubble that was bound to burst.

Not so fast, says Kip Adams of the Quality Deer Management Association.

“The fact that we have fewer deer is by design,” he says. “We have been way over (population) objective in many places, and a number of states wanted to drop herd numbers by increasing doe harvest. But it’s also true that predators–wolves, coyotes, black bears, mountain lions, bobcats, even raccoons–caused some of these drops to be sharper than intended the last couple years.”

But more worrisome than predators is the maturation of America’s forests, says Adams.

“If I’m scared about a single trend, it’s how little game our forests can support,” he says. “A young hardwood forest can easily produce 1,000 pounds of available food per acre. A mature forest produces 50 to 100 pounds. We have the same number of acres covered in trees now that we did 50 years ago, but it can’t come close to carrying the same number of deer.”

And Adams says the discrepancy in quality between habitats on private versus public land is widening at an alarming pace.

“Historically, the private and public habitat was approximately the same. But today, the average private land is far higher in quality than the adjacent public land. You have private landowners actively managing their land for wildlife. But on public land, you have a forest that hasn’t been logged and habitat that hasn’t been managed. Most of our deer hunters hunt public land, and they’re starting to notice that quality gap. It’s going to get even wider.”

A GATHERING STORM?

Distilled to its essence, what Woods, Adams and other biologists are really seeking is more active deer management. Aggressive predator control. Better disease monitoring. More proactive habitat and population assessment.

Will those things counter what appears to be a slow decline in whitetail numbers?

“Probably not,” admits Woods, who thinks predator populations are poised to explode from Maine to Florida. “I think the only thing that’s going to control coyotes is that their densities will get so great that they get a devastating mange or distemper outbreak that will go through their populations like wildfire.”

Readily adaptable, whitetails may also alter their behavior to avoid predation. They may respond as wildebeests do in lion country, by synchronous breeding, an evolutionary strategy that swamps predators by ensuring that all the fawns are born at the same time. Or deer may seek habitats where predators are less effective.

Even with these adjustments, Woods thinks rough days are ahead for American whitetail hunters.

“We will never lose our deer herd,” he says. “They’re too adaptable. Whitetails are generalists able to make a living in a variety of places. But I do think we should be prepared to return to the days when you might have to drive 100 miles to find a place to hunt, or consider it a good day when you saw one or two deer, or even just a track.”

Quantifying Risk

Are whitetails really in trouble? We assigned a risk index to a number of identified threats (10 is the most catastrophic and least solvable).

**

Maturing Forests**

Symptom: Your family has hunted the same woodlot for 30 years, but you’re just not seeing the same number of deer you used to.

Problem: From the Northeast through the Ohio Valley, the nation’s forests are uniformly old, and even intact hardwoods habitats simply can’t provide the same amount of wildlife forage and cover that they could when they were younger and more diverse.

Solution: Develop wood-products economy that promotes managed timber harvest, encourage private landowners to thin woods as part of deer-friendly habitat management

Risk Index: 8

Predators

Symptom: You’re seeing whopper bucks, but for the last couple of years you haven’t seen younger bucks or any fawns.

Problem: Wolves in the Upper Midwest, mountain lions in the Midwest, black bears in the East, bobcats and coyotes everywhere. We haven’t had a predator mix this diverse or dense since the first settlers scattered along Daniel Boone’s Wilderness Trace. Commercial trapping is no longer an effective predator management tool.

Solution: Every deer hunter needs to become a predator hunter, and wildlife managers must acknowledge that predation can be a significant factor in deer mortality. States should liberalize regulations to allow year-round recreational pursuit of coyotes and raccoons.

Risk Index: 7

**

Baiting**

Symptom: You see tons of deer when you’re scouting, but the minute the season opens, the deer disappear.

Problem: Michigan this year restored what some Wolverine State hunters think is a birthright: The ability to bait deer during hunting season. Georgia also legalized baiting. It’s legal in all or parts of 22 states. Baiting unnaturally concentrates deer, which can be a factor in transmission of disease like chronic wasting disease, EHD, Lyme disease and tuberculosis. It’s also a violation of fair-chase principles. Plus, a single bucket of corn dumped by your neighbor can negate all the deer-attracting habitat work you might have done on your property.

Solution: Abolish baiting

Risk Index: 3

******Habitat Loss**

Symptom: You don’t see any deer until farmers harvest their corn. Then deer are everywhere, including your front yard.

Problem: Expansion of rural subdivisions and urban fringe combined with a sharp increase in corn and soybean production. Carrying capacity–security cover and year-round food sources–for deer and other wildlife is declining at an alarming rate. Predators tend to thrive in fractured habitats.

Solution: Encourage the maintenance of wildlife cover, whether through subdivision planning or Farm Bill incentives.

Risk Index: 9

Intolerance

Symptom: My neighbor can’t understand why I love to hunt deer. She calls them “woods rats” and asked our homeowner’s association for permission to poison them.

Problem: Among non-hunters, whitetails have an image problem. Over the past two decades, their stature has declined from nobility to nuisance. They’re traffic hazards, petunia munchers, tick carriers, habituated pests. If tolerance for deer is eroding for the general public, it’s all but gone for farmers and residents of rural subdivisions, for whom deer have become vermin.

Solution: Promote use of regulated hunting–not sharpshooters or birth control–to manage nuisance numbers of deer

Risk Index: 9

Inadequate Population Monitoring

Symptom: Our local biologist says we have tons of deer, and he’s asked the commission to increase doe tags. But I’m scouting all the time and I don’t see any does or fawns.

Problem: How many deer do we really have? How many do hunters actually kill? State game agencies increasingly are relying on telephone or internet reporting to determine hunter harvest. And budget cuts have reduced the amount and intensity of population surveys. Without better surveys, how will we know a deer crash is occurring?

Solution: Actually, studies have found that telecheck harvest reporting is just as valid as mandatory game-check stations. The bigger problem is population monitoring. When EHD roared through the nation’s heartland, biologists didn’t know the full extent until they started getting lower-than-expected harvest reports in the fall. Instead of inadequate statewide surveys, make better use of intensive spot monitoring.

Risk Index: 3

**

Hunters’ Unrealistic Expectations**

Symptom: Last year I saw an average of 75 deer a day from my tree stand. This year I’ve only seen about 30 a day. We’ve gotta cut back on doe tags.**

Problem:** We have become so accustomed to getting “our deer” that it feels like a seasonal entitlement, so a year or two of decline can seem like the End Time. We forget all the seasons our father got excited when he saw a single doe, and all the years he tucked his unfilled tag in his gun cabinet.

Solution: Game managers must reinforce the forgotten notion that whitetail populations are dynamic, and that too many deer are just as problematic as not enough. We need to be reminded that one outcome of killing lots of deer this year is that there will be fewer next year.

Risk Index: 2

**

Leadership Vacuum******

Symptom: I go to fundraising banquets for turkeys and quail, but I’m a deer hunter. I’d like to join a group that really fights for whitetail habitat and sticks up for hunters.

Problem: Pheasants have Pheasants Forever. Elk have the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation. Turkeys have the NWTF. Even ruffed grouse have their own conservation alliance. The two leading whitetail groups, Quality Deer Management Association and Whitetails Unlimited, are smart and scrappy, but they’re also small and struggling.

Solution: Creation of a truly national whitetail conservation organization, one that is confident enough to address the wedge issues that divide deer hunters (baiting, high-fence operations, escalating use of technology) while advocating for habitat conservation, access, responsive management and research.

Risk Index: 4

Harvest Trends

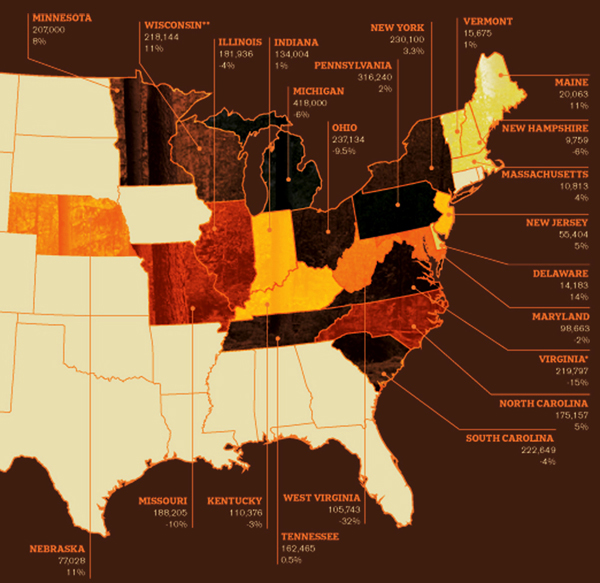

Whitetail harvest trends are both highly regional and highly “guesstimable.” Last year, for example, harvest dropped in the coal country of West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio, but Great Lakes hunters enjoyed a good year. Missouri hunters shot 10 percent fewer whitetails than the year before, but Nebraska was up 11 percent. Pennsylvania posted a 2 percent increase. New Hampshire’s harvest was off more than 6 percent, but nearby New York’s was up more than 3 percent. Instead of providing clarity, harvest data–typically based on a statistically valid sample–frustrate attempts to draw conclusions about the health of America’s deer herd on a national scale. If a state isn’t colored, harvest data was unavailable.

Row-Crop Conversion

Whitetails crave corn, right? A map of trophy buck zones matches neatly with America’s Corn Belt. Beans, too, have been good for deer. The replacement of cotton and tobacco with soybeans has allowed whitetail populations to skyrocket in Kentucky, Virginia and Arkansas.

But the world’s insatiable appetite for American corn and soybeans is troubling news for deer. Those marginal habitats–upland pastures and corner woodlots–that provide critical cover for whitetails are being plowed up and planted to small grains at a dizzying pace. These industrial-scale monocultures may provide food during the crop season, but once grains are harvested, forage and cover disappear, making whitetails especially vulnerable during lean winters.

“Those places that didn’t make sense to farm with $5 beans and $3 corn are being plowed up with $14 beans and $10 corn,” says biologist Dr. Grant Woods. “We cannot farm fencerow to fencerow and have adequate cover for wildlife.”

Death by Fangs

A 5-year study on fawn survival on the Savannah River Site suggests that less than a quarter of whitetail fawns born in the spring live until autumn. Coyotes kill the vast majority of the three-quarters that die, often within hours of their birth.

The study, led by Forest Service researcher Dr. John Kilgo, is as fascinating as it is gory. Radio transmitters implanted in the vaginas of adult does are pushed out at birth and emit a signal. Researchers race to the site, often reaching it within a few hours of birth, and then search for the fawn. If it’s alive, they fit it with a GPS collar. If it’s dead, they determine the cause of death.

“When we have a carcass, we’re looking first if it was a predator responsible, and if so, then was it a coyote or a bobcat,” says Kilgo. “This is such a remote area we don’t have domestic dogs to worry about. There are characteristics of how predators cache their prey. A bobcat often scratches leaf litter over the fawn. Coyotes often dig a hole to bury the remains. Then, so we left nothing to doubt, we evaluate the bite wounds for cause of death, then swab the wounds in an effort to collect predators’ saliva.”

Nearly 80 percent of the predation was by coyotes. The researchers’ conclusions is that the Savannah River deer herd can sustain itself with 75 percent predation, but only if hunter opportunity is diminished.

“Any prey base can only take so much mortality before it starts to decline,” says Kilgo. “Here, we had a double whammy (of coyotes and human hunters) and the only variable we could control was to reduce some of the hunter harvest.”

Is the Savannah River predation aberrant, or can we expect to lose the same percentage of fawns elsewhere in the Southeast? And if so, will states start to reduce hunter opportunity to balance prey with predation?

“Based on a number of studies that are being conducted right now, it appears that the level of predation we detected is being seen elsewhere,” says Kilgo. “It’s definitely a new dynamic. We didn’t have coyotes in South Carolina 20-25 years ago. Not only are they established now, but they are abundant.”

For an interview with Andrew McKean, the author of this piece, click The Revolution with Jim and Trav.